36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

10: Why did he do that?

My taste for science-fiction was passed on to me by my father. I was fifteen years old. My meetings with him were occasional. One day he gave me issue 2 or 3 of a new magazine called Fiction: “Read this. You’ll see, these are extraordinary stories that take place in the stars. It’s called science-fiction. The most important literature of the 20th century as I see it: that which takes us into the future, which introduces another conception of the world.”

We never spoke of it again. but he had passed on to me his passion. From then on, in my life, there would be the western on one side and science-fiction on the other. In this sense, if Blueberry is on the side of my mother and of Mexico, Moebius belongs rather on the side of my father and of science-fiction.

(Jean Giraud, Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, pp.44-5)

In the vast and mysterious epoch of my childhood, a year was a long time. Two or three years were an eternity. I learned about time-travel from comic books.

I was conscious of time because things changed. I’d been told the old people around me had once been young, like I was. But that was in a different time—I’d seen pictures. Changes were irrevocable, but many happened imperceptibly. Sometimes, however, I got my hands on a comic book a few years old, and the changes were visible under my eyes. Art styles were different. So were the layouts, the lettering, the ads. When this comic book was made, I would calculate, I was only x years old. (I had a strong if misleadingly narrow impression of what the world had been like when I was x years old.)

I think this is one reason comic books as objects became important for me. They represented an early effort at temporal orientation. The object was not merely a token; its persistence was an authentic link in a chain along which I might pull myself back to not just an earlier point in time, but to a different point-of-view.

I’ve never quite renounced these modest adventures in time-travel.

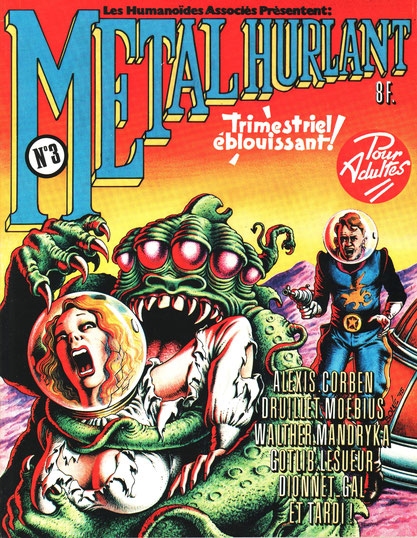

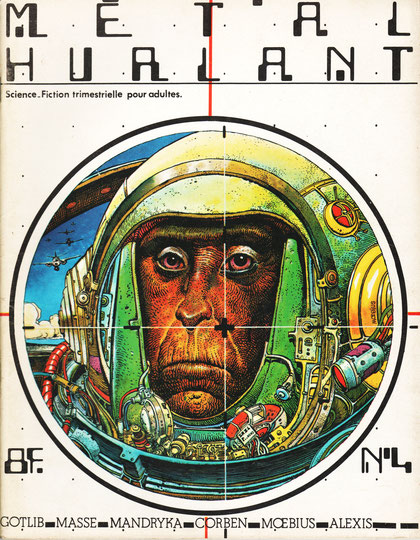

In 1975, in Amsterdam, while passing through a department store, I spotted, beside the escalator, on a low table, a small array of magazines: two issues of Metal Hurlant—certainly the third and probably the fourth. I was on my way somewhere, but I paused for a minute to flip through them. I recognized Richard Corben’s “Den”, but not the other stuff. They looked interesting but I didn’t read French, so I decided to let them lie.

Of course, when Heavy Metal came out a couple of years later, I knew what I’d been looking at. After that I always regretted I hadn’t picked up those early issues. I never considered it worth trying to get hold of them, because my decision not to buy them was made in a moment, and the moment had passed; my regret was not that I didn’t own the magazines, but only that I was unable to undo that momentary decision. To buy them after the fact would have been a kind of retrograde magic, undertaken in the service of an unanswerable nostalgia.

But last year, under the spell of Mœbius, I bought forty-two issues of Metal Hurlant, including those I’d glanced at more than four decades earlier. I felt the familiar backward plunge into another time. Looking at the covers and turning the pages, I knew what it was to be young and in love with comic books and science-fiction. I dare say it’s not at all the same today, but how would I know? I’m no longer one nor the other. But as I turned the pages, more slowly than I had in 1975, I recognized a world, or a sub-cultural element of a world, in which I’d once been a marginal if quite committed participant.

Buying Metal Hurlant wasn’t, however, a matter of nostalgia. I was in the grip, once more, of the kind of critical and historical curiosity that has occasionally taken me for a ride.

After I finished reading Inside Mœbius in 2018, I had an itch to go back and look again at The Airtight Garage. It wasn’t in print, and the copies I saw for sale weren’t cheap, so I looked instead for other things by Mœbius. But when I finished them, the itch was still there. So I took a deep breath and scratched it.

Obviously, I’d enjoyed some of what I read in the interim, or I might have let it drop; but with the Garage once more in my hands, I discovered myself a more engaged and sympathetic reader of Mœbius than I’d been thirty or forty years before. One reason, I suppose, is that back in those days I was reading widely, and never got that close. I’d been impressed, indeed dazzled by what I saw, but I was sitting in the back row, content simply to watch the show. Reading Inside Mœbius, on the other hand, was like being invited back to Giraud’s place for an informal chat. I’m still not sure whether it’s a major work, or just—at close to seven hundred pages—a substantial one; but I found it congenial, and it left me disposed to developing a more informed and alert interest in what Giraud had done.

If that makes it sound like I was embarking on a deliberate critical exercise, I’d prefer to be honest: something was tugging at me. An old hunger. An impulse I couldn’t quite explain or justify, but to which, little by little, I gave in.

And when I opened up my copy of The Airtight Garage and sat down in the sun to read the opening thirteen-page story, “Major Fatal”, I was entirely surprised by the upwelling of joy I felt. It wasn’t that I was reliving an old pleasure, because I’d always been ambivalent about Marvel’s printing of the Garage, and couldn’t remember if I’d even read the first story. (It had been in one of the issues of Heavy Metal I’d missed, first time round.) Nor was a renewed interest in Giraud sufficient to explain what I felt, because I approached both Madwoman of the Sacred Heart and The Incal with a hopeful curiosity, only to find myself rebuffed, repelled and irritated in each case. “Major Fatal”, on the contrary, I read with delight. The reason for that, I guess—and I’m only guessing—is that I’d read a lot more science-fiction in the interim, and my relationship with science-fiction had changed.

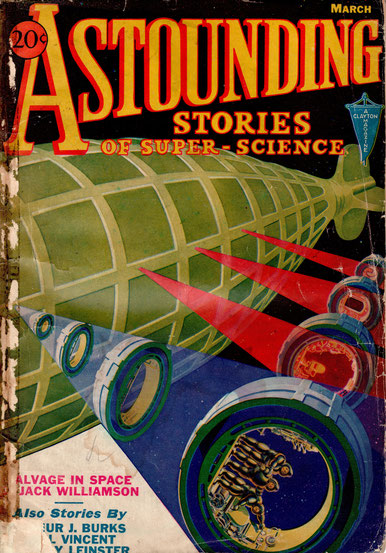

A couple of decades ago, with the aid of pulp magazines (more time-travel) I hauled myself back to the nineteen-twenties and thirties to undertake a fairly broad, if far from exhaustive investigation into what science-fiction had been before it became the genre with which I was familiar. Anthologies and occasional reprints had given me glimpses of the period, but for the most part I’d read those older stories out of a dim sense of duty, and from the slightly sniffy distance of someone used to something more polished and more pleasing. When I began a more intensive investigation, I took another tack. My own interest in sf had been prompted by the excitement I’d felt in response to certain images and stories. I reasoned that if the excitement early fans had expressed was genuine, but the stories they’d read now looked dull and out-of-date, then in order to sympathise with that excitement, I’d need to revise my standards of judgment.

Well, I did. A lot of the stories I read were clumsy, primitive, sometime dull, sometimes very dull, and often downright awful; but if their original readers tolerated their shortcomings, so, I’d decided, would I. Their tolerance may have had an original foundation in youthful ignorance and enthusiastic partisanship; I couldn’t match that, but what I lacked in enthusiasm I made up for in deliberate attention. The mere fact that a story was clumsy or incoherent wouldn’t stop me trying to get at what it had to say—or enjoying it, if it was possible it might be enjoyed.

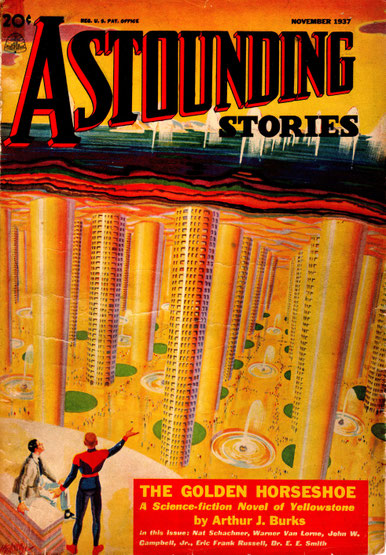

Few stories I read were as clumsy and incoherent as those by Arthur J. Burks. I remember my sense of shock the first time I read one—“Lords of the Stratosphere” in the March 1933 Astounding Stories. Reading it was like taking a punch to the guts. It left me gasping. The dialogue was incredible, the prose read like a bad, possibly conjectural translation from a language and culture remote from my own, and the characters led me to suspect the author had not actually lived among human beings. On the other hand, the story wasn’t altogether dull, and, after reading two or three more, I began to be fascinated not so much by Burks’ manner—I hesitate to call it “style”—or his haphazard and cranky plots, but by what I saw happening on the page.

Arthur J. Burks was, to quote Everett F. Bleiler, “one of the legendary fiction machines of the pulp era”. More than once, his output topped a million words a year. He wrote quickly. “It just happens,” he wrote in 1935, “that I... do my best writing at top speed...” In 1937, he confessed that

I like to write, I have to write or go mad. And the more I want to write the faster words tumble over themselves to get onto paper. I’m happy. I’m as interested in the outcome of my story as I dimly hope my readers will be—though right then I don’t think about the readers or editors or anybody else, except the matter of getting my story on paper. It burns inside me, trying to get out, and I’m happy when it’s streaking across the pages at top speed...

(quoted in Pulp Fictioneers, p.77, edited by John Locke)

In 1939, feeling the effects of more than a decade and a half of this outporing, and coming up dry, he recalled that he’d written “an awful God’s quantity of pseudo-science, because it gave rein to a wild imagination.” It’s partly the wildness of that imagination, but more obviously his haste—there’s no sign Burks ever paused to polish or revise—that exposes to view the process of narrative invention.

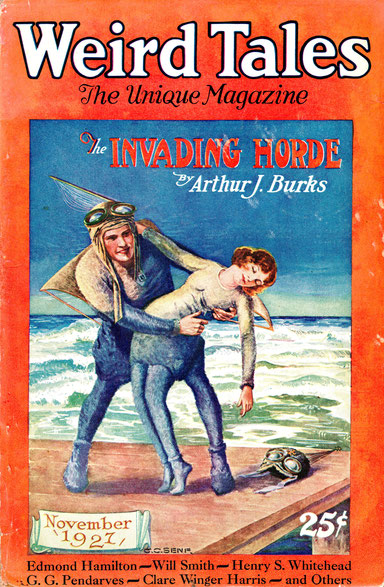

Inconsistency is the tip-off: in his first science-fiction story, “The Invading Horde” (Weird Tales, November 1927), his narrator began by telling me that

Some day City of the East will extend still farther... But all that is in the future. It will be my problem, God willing... for day by day people are being born... so that, inevitably, City of the East must grow...

I must strive... so that I can plan against the future...

(pp.594-5)

But there’s no planning against the future in an Arthur J. Burks story, where anything might happen. By the end, City of the East was no more; all its people were dead, and the narrator let me know the story I’d been reading had been written shortly before he, too, was due to die.

But if that were the case, what he wrote at the beginning—all that stuff about the future, and God willing—made no sense. If Burks had known how the story was going to end, he wouldn’t have started that way. But he didn’t know. He was inventing the characters and the action as he went along.

Pulp writers were paid by the word, and paid not very much. If they weren’t putting words on the page, they weren’t engaged in remunerative work. Burks certainly understood that. If he was unsure where his story was going, nevertheless he didn’t stop pounding the keys. He just kept going, writing whatever came to mind until he found a way forward. Sometimes he’d put questions and speculations about the plot into the mouths of characters, and, more than once, two of his puppets would hit on the same utterly preposterous notion at exactly the same time—the same time as Burks, their creator. On other occasions he’d circle around a promising or pregnant image, in the meantime filling up paragraphs and pages with the thoughts of his characters, or incidental details, or background, or whatever, but returning again to the image, sometimes more than once. When it finally suggested a way forward and gave his story impetus, off he’d go.

Of course, stories, if they’re not closely modeled on other stories, or on actual events, need to be invented. All that’s remarkable about Burks, beyond the shoddiness of his architecture, is how much of the rude scaffolding he left on show. But—and here I declare a fascination that invites no sympathy—the effect, for me, was not simply of a bad, because poorly constructed and incoherent story, but of a peculiar narrative instability in which the relationship of the present moment to its past and future was always uncertain, or open to question.

This peculiarly lively narrative instability was by no means unprecedented. As the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth, the first major novelist of the United States, Charles Brockden Brown, produced a sequence of novels he envisioned at their outset as “a series of performances”. In his journal, he wrote of an early effort that, “I had at first no definite conceptions of my design. As my pen proceeded forward, my invention was tasked, and the materials that it afforded were arranged and digested.” Sensational plots that hinge on ventriloquism and sleepwalking may appear not merely bizarre but ridiculous to the faint of heart, but Brown contrived strangely disturbing situations, paradoxical developments of character and motive, and scenes of real power. Readers with an eye for consistency, however, may be disturbed by a feeling that the stories in which these scenes occur are as precarious and uncertain as the characters who act them out.

It was with no faintness of heart that I ventured into the jungles of pulp sf. I went in search of wonders—and freaks. The stories of Arthur J. Burks were among the freaks. His plots rode a range of hobbyhorses more or less eccentric or marginal, including the racist ideology of Lothrop Stoddard, the mystery of Atlantis, reincarnation, telepathy and nudism. I’d always tended to throw myself into a story wholeheartedly, with a willingness to be carried away, but confronting stories like these required discipline. If enchantment was not forthcoming, I could, without blinding myself to their faults, volunteer a measure of indulgence and proceed to an engagement that, of necessity, combined close attention with an ironic distance.

Now, when I sat down last year to read “Major Fatal”, the opening story in Marvel’s 1987 edition of The Airtight Garage, I was already determined to give it close attention. Happily, enchantment enfolded me almost at once.

Yet, as I immersed myself in the panels and the pages, I quickly recognized that the elements of the story were hackneyed, and that I was indulging them, reading with irony. I did so with delight, because Giraud’s own indulgence and irony were perfectly evident, while mine were ready-made. Enchanted, I gave myself to the story. At the same time I was aware of the flimsy, provisional and absurd material of which it was made, I took pleasure in watching the artist at play, generously trotting out reliable clichés and contriving surprises in order to keep me (and likely himself) engaged and amused. Giraud’s deliberate and insistent foregrounding of improvisation in Inside Mœbius—as well as my own encounter with Arthur J. Burks—had paid off: it was as if I was reading over Giraud’s shoulder at the moment of creation.

Back when I was first reading Mœbius, I’d have been hostile to the idea I needed to be aware of and sympathetic to the element of improvisation in Giraud’s work. Let the story speak to me as it will, I’d have thought. Who cares how it was made? Let me respond to it as I will. I’ve never been a great one for jumping through hoops in order to know the right way to read something, and if you’ve come this far and are doubtful where I’m heading, I trust you’ll read this as an encouragement to take your own tack whenever you please. I did, and I’ve done it in my own sweet time; with the unanticipated result that an increased sensitivity to the characteristics of improvisation has enhanced my enjoyment and perception of Giraud’s work. If nothing else, it has released me from a tendency to judge the Garage by its inconsistencies and by its “plot”.

“Comic strips,” wrote Giraud,

possess a dimension that seem to me essential: that of play. The Gir/Moebius duality is a game. A terribly serious game like the games of children...

This duality is born of the idea of a double exploration: the one a drum beaten by Gir, in the traditional context of the comics industry... the other shaped by the secret life of Moebius, made of sadness, of impulses, of passions, in perpetual quest of the appropriate expression...

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.15)

When, in episode 3, Giraud wrote that “ANYTHiNG CAN STiLL HAPPEN iN THE HERMETiC GARAGE”, it was a little bit more than simply a gag. It was a statement of intent...