36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

12: A note on Blueberry

It’s always very hard to analyze one’s own strengths and weaknesses... I think I’m someone who is able to do a lot of things, in a lot of different styles, in an average sort of way. For all these different styles, you could find artists who are much better than I. For instance, there are better western artists than I, and there are better science fiction artists too. But I just happen to be able to do these two genres fairly well.

(Jean Giraud, Comics Interview #75, 1989)

When I was very young, and read as many comic books as I could get my hands on, I had the opportunity to discover, and began to recognize, different art styles. At first, it wasn’t a matter of knowing the names: I’ve no idea when I discovered “Dick Sprang” was the name of the guy who drew Batman that way, but obviously it was very different from how Carmine Infantino later drew the character, or Neal Adams.

For obvious reasons, strong styles made the strongest impressions; but artists are rarely so lacking in character that, even in less distinctive work, their own particular habits and tics don’t show through. A basic choice for a representational artist is to what extent the artwork ought to form an accurate transcription of the world it represents. “Wanting to represent reality through drawing is an enterprise fatally doomed to defeat,” wrote Giraud in his memoir, Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double (p.170); but even if cartoonists are bound to grapple with the practicalities of constructing, visually, no more than a plausible substitute for the world, their choices extend to things like how to draw shadows or wrinkles, how much detail to put in or leave out. The opportunities for idiosyncrasy are manifold. I remember getting excited, one day, when I actually saw someone with the kind of nose Robert Q. Sale used to draw. I’m not convinced I ever saw anyone wear glasses the way Clark Kent did when Wayne Boring drew Superman.

Though it became evident most artists displayed some kind of evolutionary shift over time, it was also usually the case that their styles, at a given period, were largely defined by such choices and idiosyncrasies. The work of Bernard Krigstein was a notable exception. While the characteristics of his drawing may be recognized, his style (in work for Hillman, EC, DC and Atlas, among others) often varied from strip to strip. When he cared (which he didn’t always) he was willing to engage with each story, in an effort to realize possibilities inherent in its subject or theme, using whatever graphic and narrative approach seemed appropriate at the time. Each strip, however, was of a piece—a thing in itself, stylistically consistent.

I offer this by way of preface to an observation concerning Giraud’s work.

Having tracked down as much Mœbius as was practicable, and having committed myself to writing something about what I’d been reading, a small dereliction of duty began to niggle at me. That what Giraud did as Mœbius was something different from what he did on Blueberry is well-attested; but it was also clear that my sense of what Mœbius differed from rested on an impression three decades old. That’s how long it had been since I read Marvel’s Blueberry #1-5. These volumes were subsequently collected in hardcover by Graphitti Designs; and when, at the end of 2020, I ascertained that the publisher still had some copies for sale, I bought them, and read them.

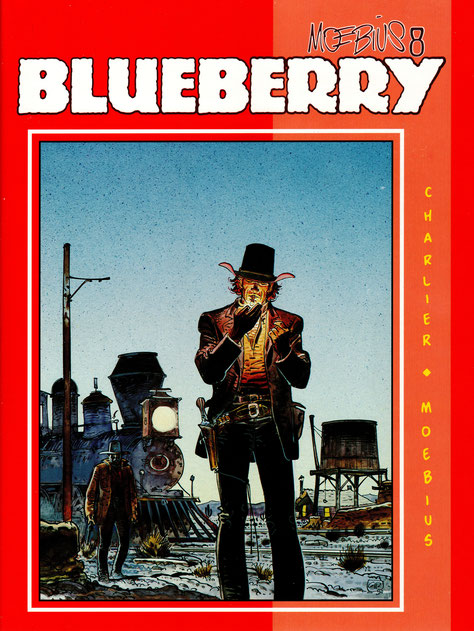

Blueberry, by Charlier and Giraud, is a western pot-boiler full of chases, fights, ambushes and escapes. The plots are animated by a fair amount of misadventure and bad faith. It ran almost continuously for a decade—sixteen albums’ worth—beginning at the end of 1963, in the weekly Pilote. A further six albums appeared over the next seventeen years, with Arizona Love the last scripted (in part) by Charlier. Giraud finished it, then wrote and drew another five albums between 1994 and 2004.

Graphitti’s hardcovers collect the fat middle of the series, from the seventh album to the twenty-second. (Mœbius 8, 9, 4 and 5—in that order, if you’re interested. Mœbius 6 collects the spinoff series, Young Blueberry.) I had great fun reading them, not least because it reminded me what it was like just to plunge in and read comics, page after page, hours at a stretch, day after day, in a way I haven’t read comics in what feels like a hundred years. But I also discovered two things that surprised me. The first was that Jean Giraud didn’t have a very strong or pronounced style.

It seems an odd thing to say, considering the indelible impression made on me, forty and more years ago, by the work of Mœbius. Yet I remember that, not long afterward, when I read the earliest Blueberry books in translation—beginning with the first, Fort Navajo—I found the stories engaging, but looked at the pages, largely in vain, for signs of Mœbius. The narrative flow was smooth, but the art seemed almost anonymous. (If you’re curious to see what Blueberry looked like in 1964 and 1965, you might check out the first four albums on Internet Archive.) It may be fair to say that Blueberry had rather a basic representational style, which was enhanced, in the course of time, by Giraud’s developing mastery of technique.

The earliest album collected by Graphitti is the seventh, The Iron Horse—Le Cheval de fer, which began serialization in Pilote in 1966. Giraud’s willingness to experiment with the handling of ink is becoming evident, but some of it’s pretty stiff. There are panels that wouldn’t have looked out of place in a second rank back-up strip in a neglected Marvel western title round about the same time...

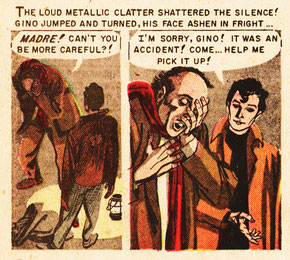

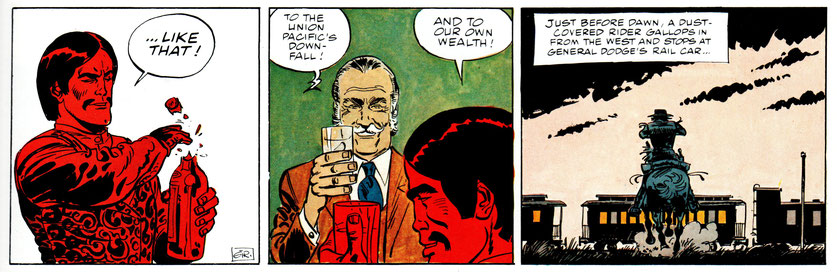

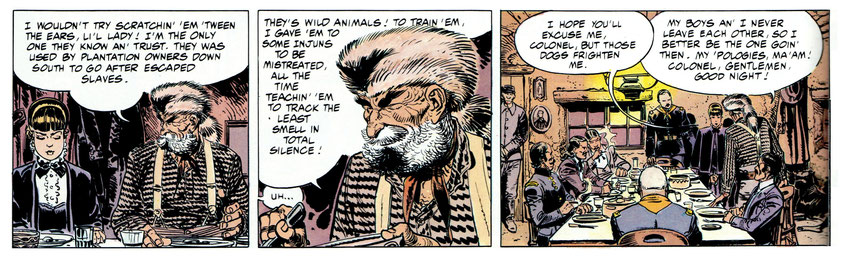

The next album, Steelfingers (L’Homme au poings d’acier, June-November 1967) sets off with a loose, brush-heavy look, open to cartoonish humor, as if Giraud was taking a stab at working in a primitive Jack Davis style.

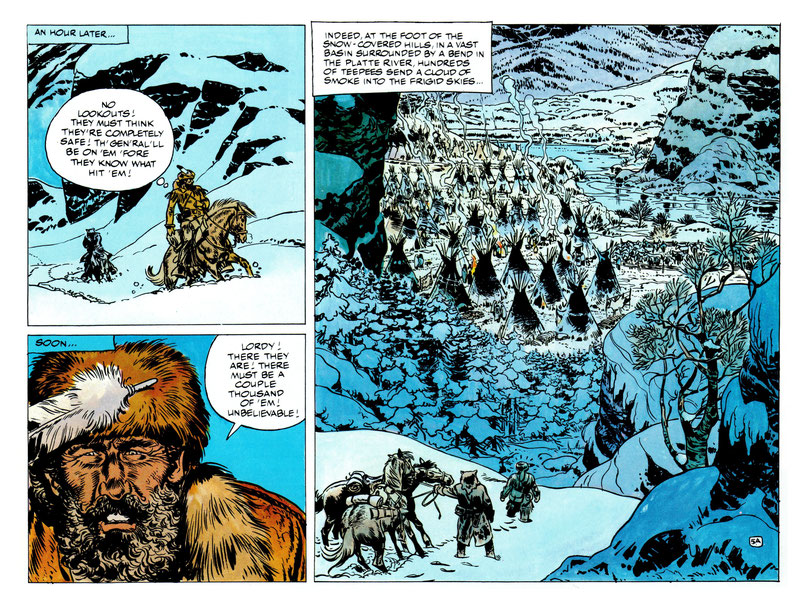

Overall, the art is less consistent and less attractive than in the previous album; but in The Trail of the Sioux (La Piste des Sioux, December 1967-May 1968) the fast, elastic brushwork gains in confidence and consistency throughout.

From its opening, General Golden Mane (Général tête jaune, July-December 1968) displays a deliberate increase in the care with which individual panels are handled; and some pages begin to look handsome as a whole—a matter of little account, up to this point.

Despite occasional lapses, the album represents a major advance in both pictorial and narrative terms.

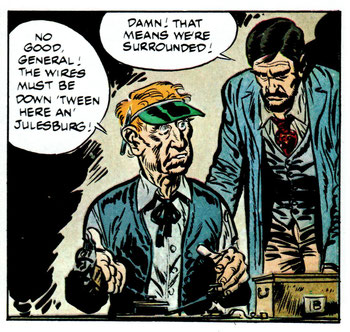

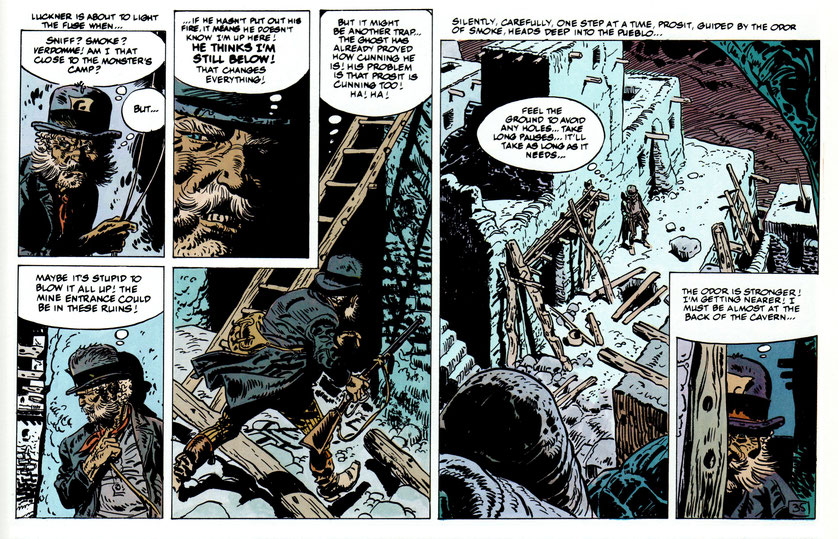

The Lost Dutchman’s Mine (La Mine de l’Allemand perdu, May-October 1969) begins by surrendering some of the scenic advances of the previous album, in favor of a more character-focused narrative cartooning; but it gradually mutates as the story progresses.

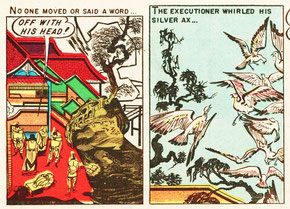

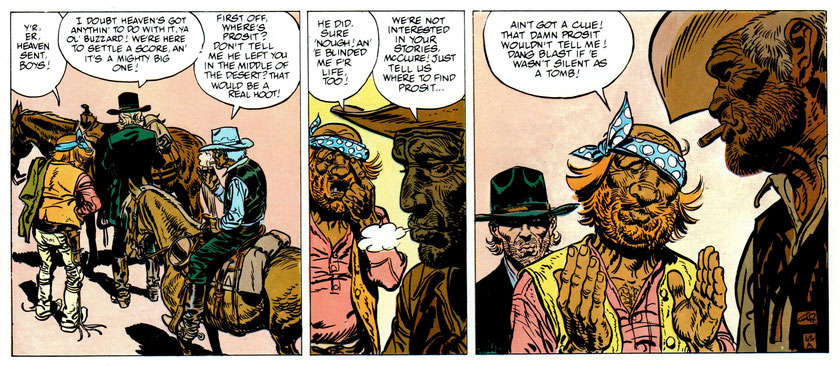

The sequel, The Ghost with the Golden Bullets (Le Spectre aux balles d’or, January-July 1970) starts with a much drier inking style,

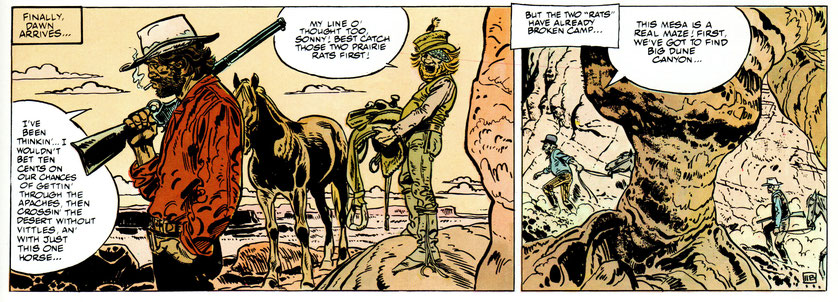

developing an illustrative weight in places,

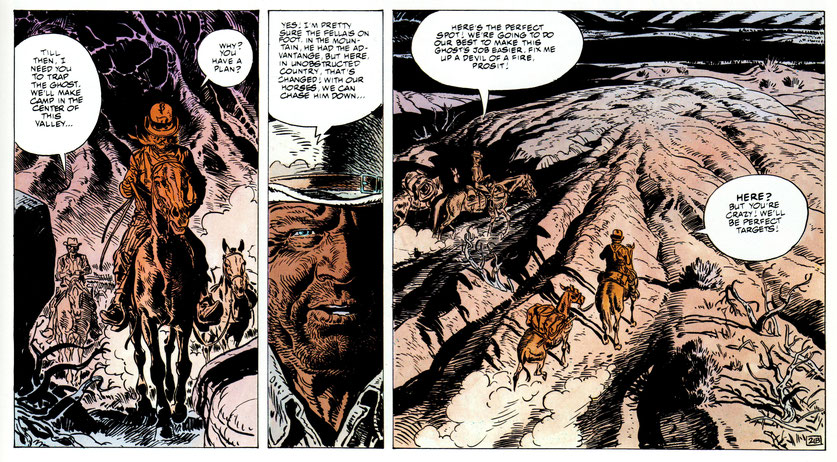

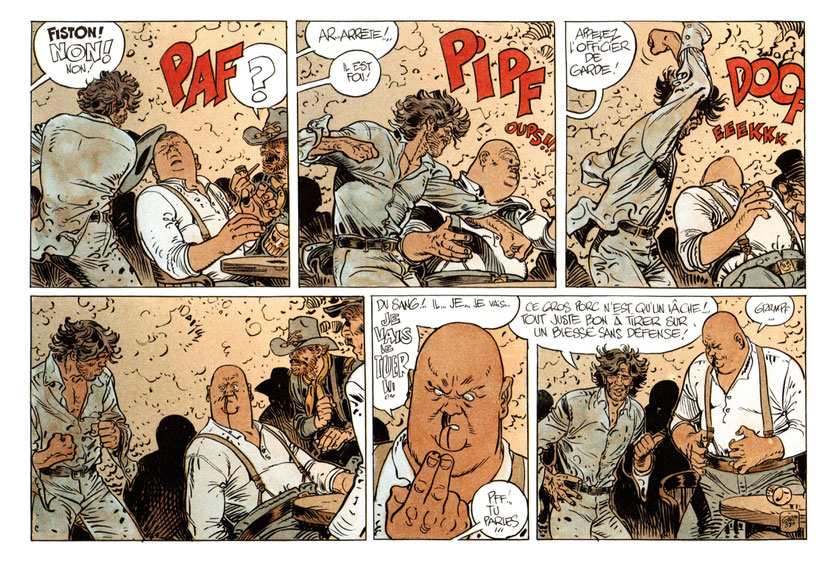

but returning again to vigorous and confident cartooning as it comes to an end.

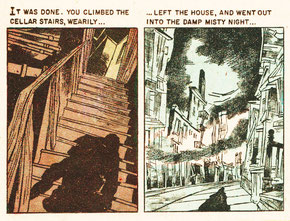

Giraud later wrote that, in these two books, he’d been “at the top of [his] form,”—at least in terms of his engagement with the material. In the books that followed, his style continued to change, but no clear line of progress can be charted. The rendering is sometimes careful, sometimes loose. Variations are sometimes adventurous or playful, but sometimes suggest weariness or haste. After years of drawing Blueberry, he’d begun to have, at least some of the time, “a feeling of frustration, of being trapped.”

I think you can tell that The Outlaw [the sixteenth album, Le Hors-la-loi, April-August 1973] is the last Blueberry story before Moebius. I had reached the point where Moebius had to take over because Blueberry alone could no longer be the medium to carry my emotional charge and desire to grow and to dream.

(Jean Giraud, Afterword to Ballad for a Coffin)

In histoire de mon double, he wrote that during the first ten years of Blueberry, he’d experimented with “practically all” that he later did as Mœbius (histoire p.164). Even so, subsequent Blueberry albums are not by Mœbius. Broken Nose (Nez cassé, 1979) features his most deliberate and consistent work on the series, prior to Charlier’s death, and was drawn at the time of Mœbius and Metal Hurlant—but it’s not Mœbius.

Gir works within the constraint of narrative logic imposed by Charlier’s scripts. There are rules to respect. Moebius is free poetry. I invent my own rules as things develop... There is not one Moebius but many, each time different. They have the infinite variety of emotions and sensations of life... With Moebius, there is a larger part of adventure, of improvisation...

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double p.166)

As in the beginning, at Hara Kiri, Giraud as Mœbius freely played with different syles and approaches, now securely grounded in years of solid practice. Shorter works tend to display, within themselves, a unified look, and so, by and large do individual installments of the Garage; but the Garage also displays, from one month to the next, a playful and occasionally startling elasticity.

This brings me to my second discovery concerning Blueberry, which is already, in some measure, illustrated by what I’ve written and reproduced above. That I account it a discovery tends to suggest I was asleep when I read the series three decades ago:

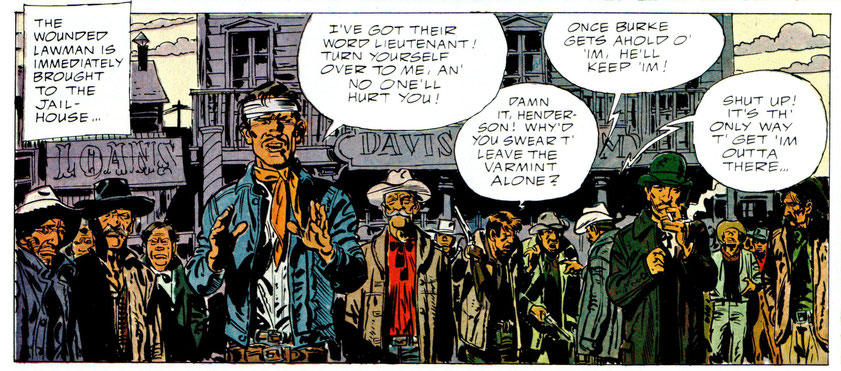

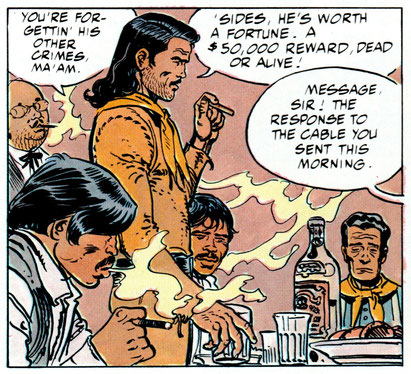

Giraud didn’t have one style as “Gir”, and a different style—a range of styles—as “Mœbius”. Blueberry, too, displays an elastic drift within each album. Harnessed to narrative, and to what Giraud conceived as the generic rules of the western and the necessity of realism, the art rarely varies as jarringly, as whimsically as it does in some phases of the Garage—but the style never settles for long. One reason I had so much fun reading these books was that every few pages I’d see something that reminded me of Alex Toth or Milton Caniff or Lee Elias or Harvey Kurtzman or Will Eisner, and I don’t think it was exactly an accident. Even in Broken Nose, the most careful and consistent Blueberry before the late “Tombstone” cycle, there’s a panel that stopped me in my tracks and put a smile on my face.

On page 14, Wild Bill Hickock is one member of a dinner party. His face, in profile, is finely polished in a way that suggests it might have been drawn by Russ Heath. I’ve not the least doubt Giraud adapted the work of other artists from time to time, but it would take more time than I’ve got to establish whether this was a swipe, or just a coincidence.

But if Wild Bill was drawn by Russ Heath, what about the guy in the bottom right of the panel? Was Al Fedstein warming Giraud’s seat when that face was inked?

Following Charlier’s death, Blueberry underwent something of a change. The final five-album story is less linear than anything that preceded it, incorporating a long flashback whose action precedes the reckless and headlong series that began in 1963. Published as a stand-alone album in 2007, the flashback became a prequel that ended with Blueberry setting off for Fort Navajo.

At the end, Blueberry returned to its beginning, but enriched by four decades of experience. Giraud was pretty much at the top of his game, and OK Corral, which follows a couple of dozen characters through one night and into the early morning of the day of the shoot-out, is, for my money, a highpoint in the series. But, however it had changed, the Tombstone cycle nevertheless remained faithful to the principle that, in Blueberry, the art would be formed in the service of narrative. It still wasn’t by Mœbius.

In a conversation with Jean-Marc Lofficier in 1989, Giraud pushed back against the notion that his work as Mœbius was more personal than the work he did as Gir:

I consider that the work I do with Charlier is as personal and as important to me as the work I do on my own. My relationship with [collaborators] are intensely personal relationships, and so are the strips we do together.

This may be read as an expression of fidelity to his long-term collaborators, primarily Jean-Michel Charlier, and also an acknowledgement of his investment in (and debt to) Blueberry.

But, a quarter of a century later, when Giraud’s characters—Arzak, Malvina and the Major, Atan and Stel—prepared to enter the cantina of El Coyote, in the last book of Inside Mœbius, Blueberry preferred to remain outside...