36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

15: Apart from the usual details...

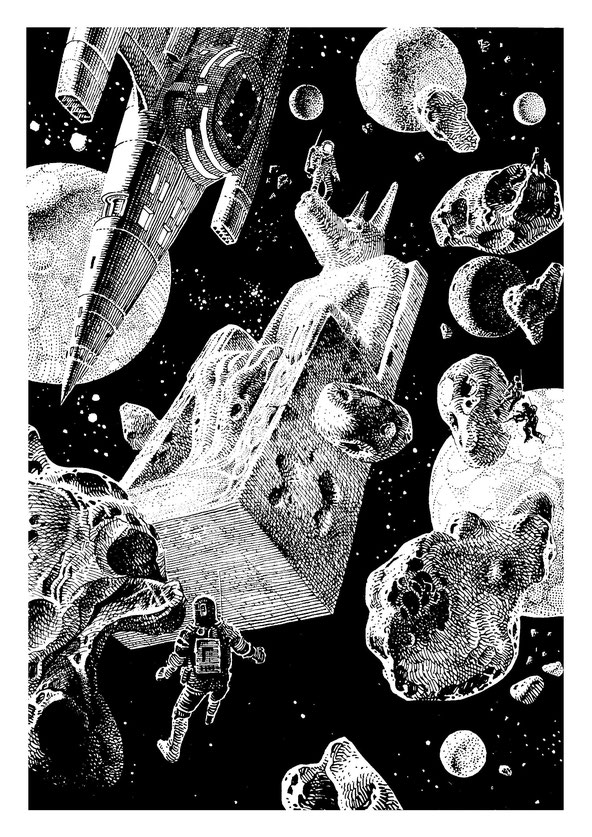

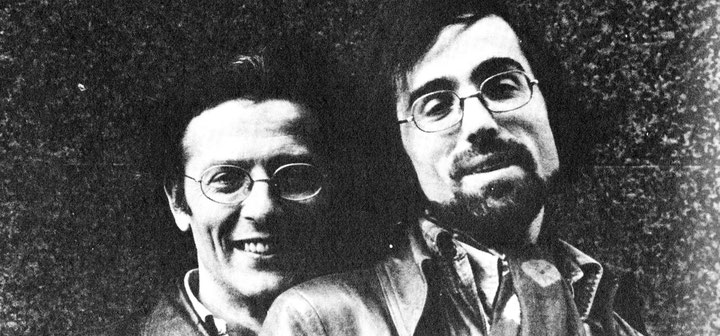

When I did “The Detour”... I was between Blueberry stories. At the time, as Moebius, I was also drawing SF illustrations. My friend Philippe Druillet was always nagging me to do a comic story in that style, but I was too lazy.

(story notes to “The Detour”, MŒBIUS 2: ARZACH)

When he wrote that Druillet was nagging him to do a story in “that style”, what did Giraud mean by “that style”? His approach to illustrating sf was even more open to variation than his approach to Blueberry.

If he wrote that he was “too lazy”, does it suggest his sf illustrations involved more work? He said as much in conversation with Jean-Marc Lofficier:

If I did my SF work in the same style as my Lt. Blueberry work, that is, very realistic, using a brush, with lots of shadows, etc., it would probably be fairly easy...

(Comics Interview #75)

—but there he was talking about his sf in comics, rather than about book and magazine illustrations; and he conceded that the essential difference lay not in the art style so much as the creative process. When he set about drawing “The Detour” in 1973, however, he did employ a labor-intensive pen-shading style, very different from his work on Blueberry.

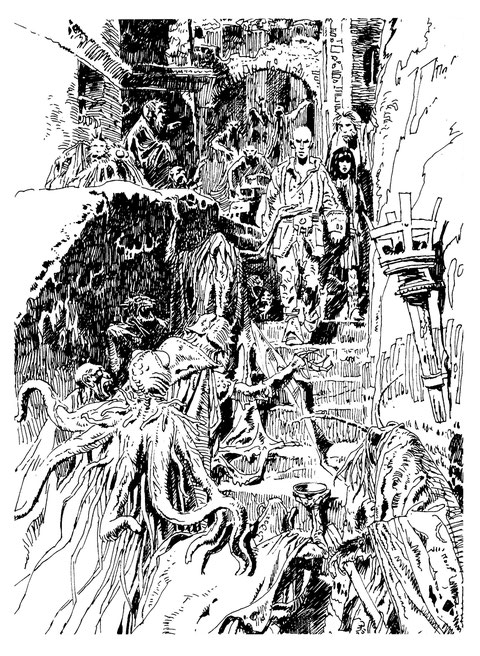

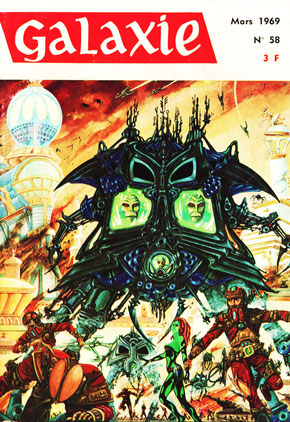

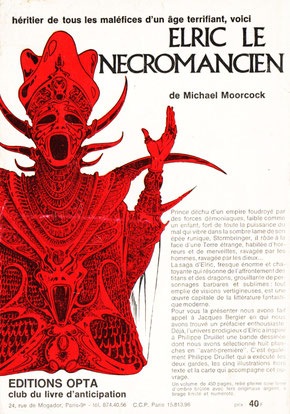

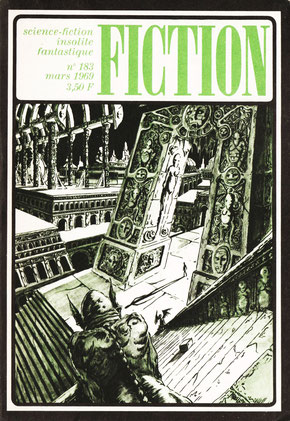

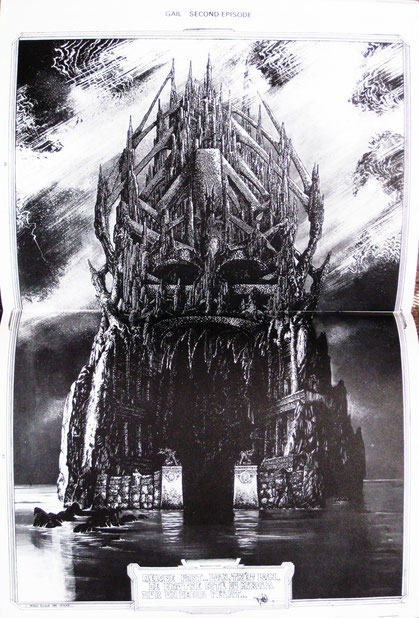

Like Giraud, Druillet, at the time, was doing illustrations for Opta’s magazines and books...

... and had been successfully producing his own brand of science-fiction in comics since the mid-sixties. Giraud had been working as a professional in comics for longer, but Druillet had taken vaulting and grandiose leaps into the fantastic, whereas Giraud, saddled with the hugely successful Blueberry, had published only a couple of sf shorts in Pilote Annuel.

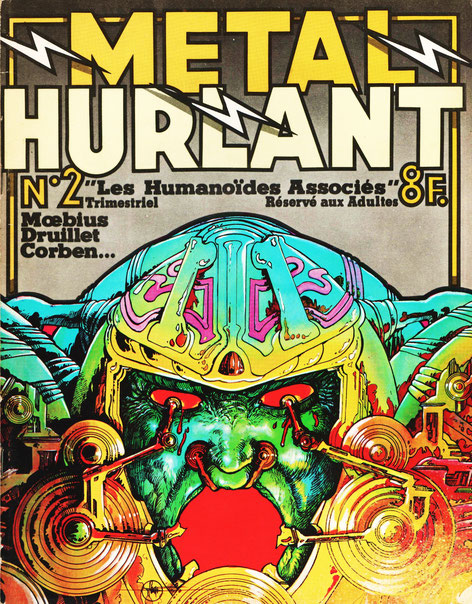

Druillet was not only Giraud’s colleague, but a friend. He knew Giraud was an enthusiastic reader of sf, and was evidently trying to encourage him to apply himself to work in a genre by which they were both excited. Within a couple of years of “The Detour”, the stars were in conjunction: along with Jean-Pierre Dionnet and Bernard Farkas, they joined together to form Les Humanoïdes Associés, in order to publish a comics magazine devoted to science-fiction and fantasy—Metal Hurlant.

And that, I suppose, serves as a short account of Druillet’s role, as midwife, in bringing Mœbius to full term.

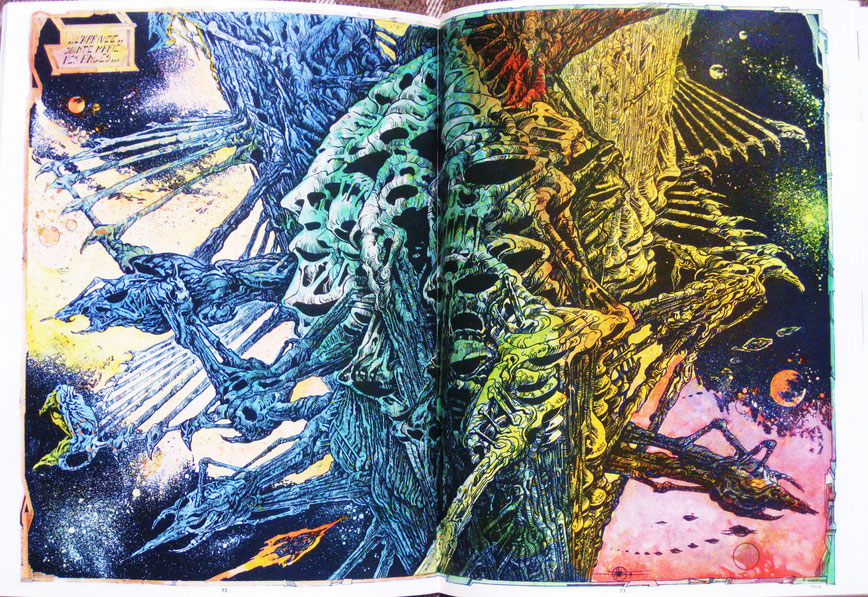

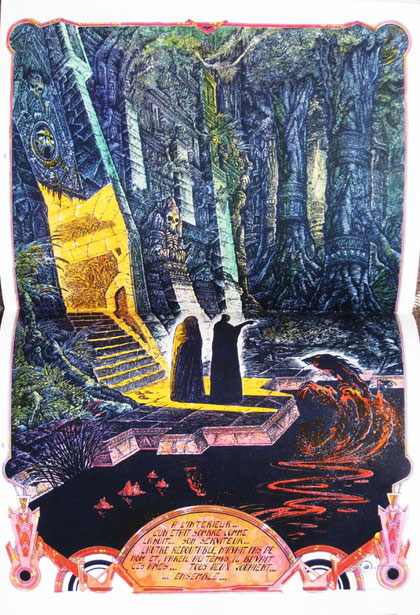

Though they were friends and (very occasionally) collaborators, their work is dissimilar in most respects, and my response to their work has been likewise dissimilar. I rather wish I’d been better able to read Druillet’s work, because I was always attracted by it. His images often conveyed a jagged, hectic energy, and in his use of full pages and double pages he was a contemporary, in the early seventies, of Jack Kirby. But I’d been reading Kirby for about as long as I’d been able to read, and was never able to bring to Druillet’s work the same reflexive indulgence. Moreover, the pages by which I was attracted worked, for me, only so long as I didn’t look too closely. The detail didn’t engage my sympathy, and my attention tended to skitter away and settle on the text, which usually failed to hold my interest. Druillet’s stories seemed to open onto an illustrated world of spectacle, rather than a narrated world. Bound by my hunger for narrative, I caught only glimpses before the images flattened and the world fell apart in the face of my disappointed enchantment.

Well, that’s my own problem, not a complaint. Blessed be those who delight in the work of Philippe Druillet, for theirs is a treasure I share in only small measure.

Yet if Druillet wasn’t illustrating stories so much as draping illustrated worlds on a slender framework of story, doesn’t this also describe what Giraud was doing? Most of his stories as Mœbius in the seventies were little more than vignettes and anecdotes; yet with these—and with the Garage, of course—he gained the admiration of a generation of readers.

The Arzach stories (1974-75) are a case in point. There were only three—solid, if slight—and a set of unconnected pages. They opened a window onto a world with its own history, its own culture, and likely its own languages, about which readers were told nothing. We were shown, and permitted to wonder. I remember repeatedly turning the pages, trying to decide how the third story related to the first two, and how the pages of the fourth might relate to one another.

(The new story in Marvel’s 1987 collection, which resurrected two of the more anomalous images in an attempt to provide some background, demonstrates the level of impoverishment to which the determination to “explain” a mystery may descend. The late Arzak (2009), on the other hand—the first part of what was projected as a three-book series—is a very much more deliberate act of storytelling, and realizes a narrated world separate and distinct from the one envisioned three decades earlier.)

If the pages of the original Arzach appear to advertise a coherence that proves ultimately inscrutable, the coherence of the Garage is altogether more tenuous and unstable, even at first glance. If the eccentric and loose-jointed story is more illusion than accomplished fact, is the magic that sustains my interest after forty years nothing other than the delight I take in how it looks?

It may be that, but it’s also always been more than that. Where, for me, Druillet’s pictorial world flattened, Giraud’s deepened into three and four dimensions. If his invention is primarily illustrative, nevertheless illustration doesn’t merely decorate, but constitutes the narrative. I’ll try briefly to indicate how—and to what extent by drawing—Giraud propelled himself through the opening phase of the story, and on to a journey that lasted half a lifetime. This is simply a descriptive sketch. I pretend no insight into the artist’s intention, or state of mind:

Having opened with an absurdist gag, Giraud found a way to continue in episode 2 by picking up on the character named by the title—Jerry Cornelius. But he declined to draw Cornelius, substituting instead a rather odd science-fictional truck, from which the character’s voice, speaking by radio, is seen to issue. Giraud drew the vehicle crossing a cold desert. Deserts nurtured his imagination, and the world of the Garage would be rich in desert areas.

In episode 3, picking up from the title again, this time he drew the garage. The name of the proprietor may be seen above the door. Other details—the guards, the sculpture in the background—provided material that would be reused later in a narrative Giraud, at this stage, was still trying to confound. He thwarted his protagonist (Barnier) for a third time (abandoning him in a very awkward situation) in order to import, from a handful of earlier strips, the whimsically mutable figure of Major Grubert.

Giraud was willing to tell the reader Grubert had a spaceship, and even gave it a name; but it was a spaceship as lacking shape and location as Cornelius’s vehicle lacked an interior.

The interior of the garage in episode 3, however, had come alive. One detail was a poster featuring a comic-strip character; it provided a springboard for the adventure, in episode 4, of a giant robot dressed as the Phantom—the “Star Billiard” advertised at the end of 3. In episode 5, the Major and his consort Malvina may be seen interrupting a game of billiards in order to look at the photograph that gave Jerry Cornelius a face and substantiated his narrative presence even during his subsequent prolonged absence.

It’s a serial whose episodes are as likely to end on a conundrum as a cliffhanger, and episode 4 plumbed the depths of absurdity by having its characters descend a stairway before opening a door leading directly into a railway carriage. Visual echoes of that carriage may be seen in some panels of 5, but it was in 6 that Giraud first drew the splendid steam engine. The three panels of episode 7 were devoted to a depiction of the train, the carriage, the two characters introduced in 4, and—this was new—an airplane’s attempt to bomb the train. When episode 8 picked up where 7 left off, the serial was in danger of becoming a story; but Giraud quickly frustrated this element of continuity, then used the second page to draw a location repeatedly mentioned (2, 5, 7) but as yet unseen. How did Barnier get to the Singing Caverns? He was drawn there, obviously.

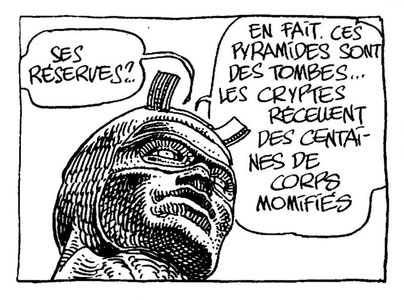

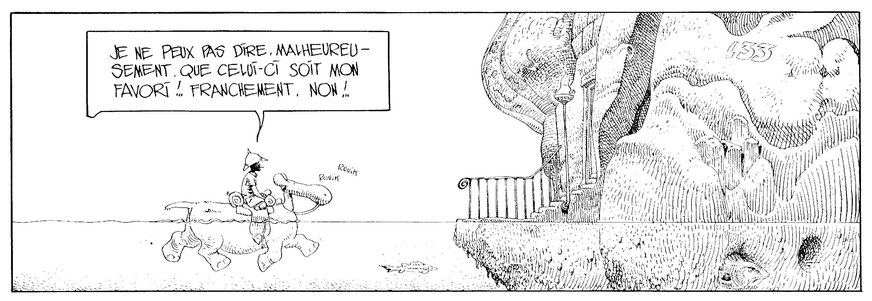

In episode 9—whose continuity with 6 is both obvious (Grubert is riding on the back of his malro) and problematic (the location is not so obviously the same)—Giraud drew the once-seen, but never to be forgotten Mausoleum L33. It’s a structure so imposingly odd that my initial impression of what it implied about the story, and the world of the story, has never quite settled to a certainty.

One might divide up the body of the Garage in a number of ways. The simplest thing is to accept it for what it is—a serial story consisting of thirty-six installments; but an unhappy incident in the Cafe Viennax (18-19) may be viewed as the climax of a first half that itself has two movements, beginning with the introductory scherzo of diverse styles and reckless invention sketched above. I trust it’s a sketch that won’t be mistaken for a description of the story.

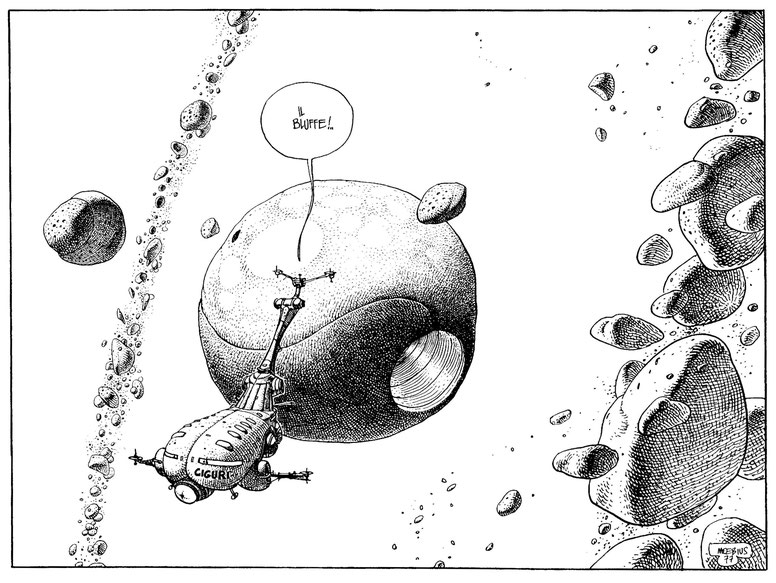

The second movement opens with Grubert’s entry into Armjourth in episode 10. Though it developed the action more coherently, illustration may still be seen to take the lead: four characters were produced in 10 and 11 who would be variously introduced and identified over the next five installments. Giraud was playing illustrative catch-up when he finally got around, in 12, to drawing the Major’s spaceship...

... but the illustration originally anticipated the first mention of the asteroid in 15, as well as its “explanation” in 16.

Giraud’s procedure in constructing the serial appears to have involved a curious parallel to our experience of the world in which we exist: first we find ourselves in it, then begin to learn about it. Giraud first drew the world of the Garage, then elaborated the story he found there.

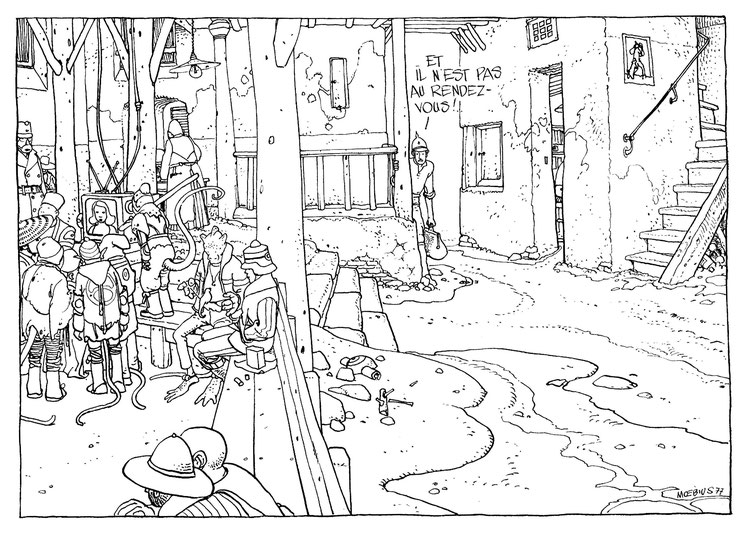

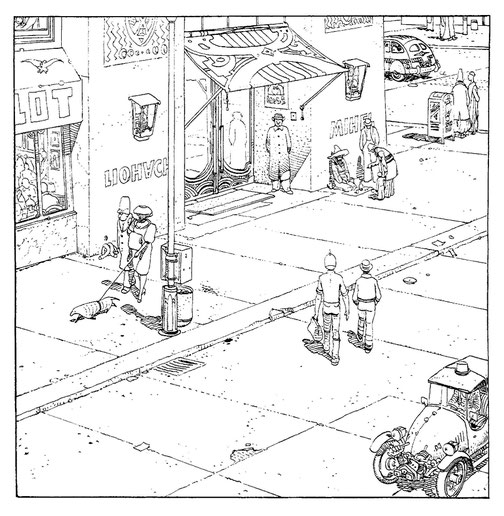

Armjourth, the mysterious capital, was also invented piecemeal, panel by panel. There was the name, of course, but until Grubert entered a chamber where sacred music was being performed, it was only a name. Nothing bound it to the story beyond the fact that Cornelius was making his way toward it—don’t ask me why. After the chamber came a series of busy thoroughfares, quieter back alleys and dingy corridors. When Grubert was led, in 13, toward what turned out to be the holog, it looked rather as if he must be on the very outskirts of the city. Later (30, 34) there were glimpses of a more extensive urban area, but the nearest Armjourth came, in the Garage, to resembling a coherent location was in episode 21. A sequence of three panels supplied the city not only with a skyline, but suggested a range of altogether mundane opportunities. We see a very ordinary street, not too busy, full of ordinary details...

The few pedestrians are humanoid, if not exclusively human. Cars and costumes are only mildly exotic. There’s nothing exotic at all in occasional signs of litter and disrepair. For a moment, the city is not merely a background, but might be a place where its inhabitants live even when the action of the story isn’t passing in front of them.

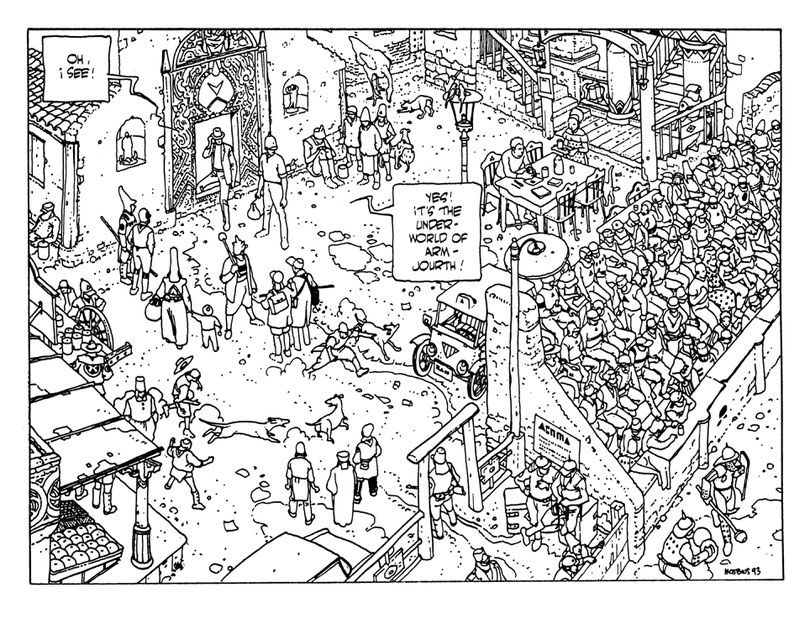

In 1993, Giraud would bring Armjourth more persuasively, albeit briefly, to life. In the uncollected episodes of The Man from the Ciguri, Grubert re-entered a city from which he’d been absent for about a day—and a decade and a half—and in panel after panel it’s inhabited by men and women (old and young), children, dogs, strange birds and other animals. There are courtyards, towers, apartment blocks, broad roadways busy with taxis and buses, and a bridge across a river on which barges ply their trade. We see sporting events, market stalls, and even a funeral parade for Federico Fellini. And, as markers of civilization, there are signs, there is trash. Armjourth is no longer merely a whim; it’s a place that breathes time, its people are in the midst of life. Everyone has an interest—something to do or nothing to do; somewhere to go, or nowhere—but their conversations, their gestures, their sidelong glances tell us their moment under our view is but a moment out of a lifetime.

A moment for the reader. It’s we who are transitory. We see the Armjourthians for a moment, in passing; but they shall endure—at least, as much as anyone endures. Of course, the children at play and the dogs know nothing of this, concerned only (and rightly, perhaps) with their moment of play.

Here, Giraud was no longer using illustration to invent story; he was substantiating it. Yet the world of the Garage and its moment of invention were precariously and intimately conjoined, and as Armjourth gained in reality, the story in which it had its life lost momentum.

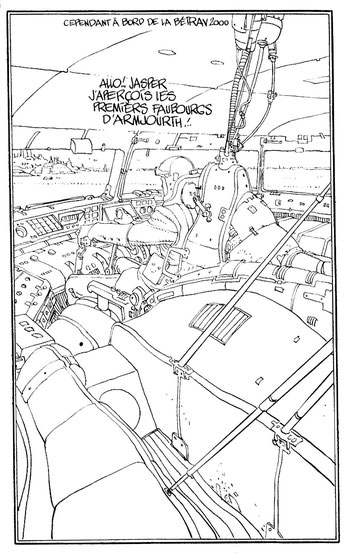

Even later chapters of the original Garage display a tension between the diversity and often singularity of the illustrations and the possibility that a story might actually be holding them together. Cornelius’s vehicle was still making its way, urgently, toward Armjourth when (in episode 28) Giraud drew the one and only panel showing its cabin or cockpit:

The image is visually light, executed in lively but careful lines, without shading, while the space it depicts is itself plausibly cluttered and confining. It’s a cool image, superimposed on an installment with whose action it has no direct connection. On the other hand, Giraud’s decision to finally produce Cornelius in the flesh (even if only as an all but anonymous figure, viewed from three-quarters rear) may be seen, in retrospect, to announce his determination to bring the serial to an end. And, indeed, story appears to have caught up with (or even preceded) drawing in this case, for Cornelius is at the same time communicating his arrival at the broad outskirts of Armjourth to the faithful Jasper, with whom he’s been in radio contact since the second installment.

But if Giraud was determined to get out of the Garage, and had, by this stage, at least the outline of an exit strategy—destabilization of the world of an already unstable serial, and reduction of the cast to its essentials—he still had to draw his way out before the last of the clotted plot’s surprises could be sprung. Episode 34 is almost void of narrative content, beyond the obvious fact that Grubert and Cornelius are drawn together and set on their way; and the intermediate zone of 35 is as much a portfolio of sf illustration, cartooning and page design as it is a preparation for the long-winded who-done-what revelations of the final chapter.