36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

16: L’art chez Jean

... All the work of Moebius aims to bring to light the grave neurosis born of not feeling myself socially involved, nor even historically, in the world in which I develop. People like me have always existed. By pure accident, I live at a time when a planetary consciousness is emerging and proposes to transcend national and cultural particularisms. This effort to see ourselves on a galactic scale is something I wanted to give an idea of through the work signed Moebius. The solution is in the transcendence of our internal field of vision, by the creation of an external space, from which we might regard the Earth, staring at it without seeing it, so as to have a chance to perceive, through meditation, its immanent being. We achieve this more easily when, by nature, we refuse our culture, our language, our family, and seek, at each instant, to reinvent the world.

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double p.173)

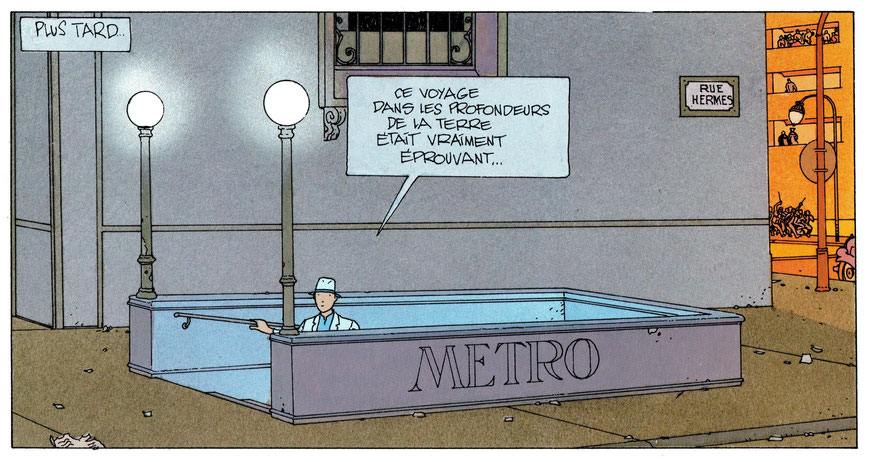

In L’Homme du Ciguri, a direct sequel to the Garage, Gruber (as he was now called in French) emerged into a world that wasn’t quite the world he’d entered at the end of the original serial. Then, he’d escaped a fictional world by finding his way to the commonplace world of contemporary Paris—not the real world, but a representation sufficient to indicate that fiction had run its course. Giraud, too, was escaping from the Garage, and from Paris; and readers were obliged to get along without a serial that might (like so many serials and soap operas) have continued indefinitely.

The transformation of the world of the sequel, from one as banal and as marvelous as the world in which we live, to one which, despite the resemblance, is open to the invasion of beings from other worlds, from the future, and from alternate realities, is simply explained: fiction is resumed. The story takes up where it left off, and Gruber is once again under Giraud’s pen.

But Gruber remains separated from the world of the original serial when the sequel begins; and, as far as that part published as a book is concerned, he’s still only on the threshold of returning when it ends. The arc of the story, however, carries him dangerously close to the actual foundation and origin of the fiction to which he belongs, as Giraud revisits and reviews a project that began, a long decade and a half earlier, almost by accident.

Except, of course, that Giraud didn’t exactly believe in accidents:

My religion is that we make the world. Chance intervenes in the way the world responds to our unconscious will.

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double p.18)

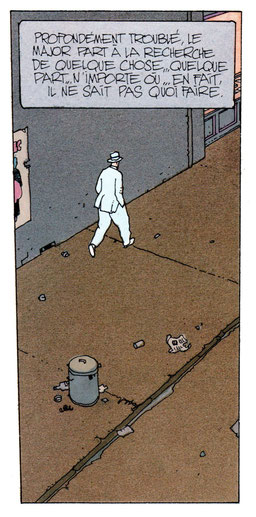

Prevented (by Tar’haï magic, I suspect) from reaching the local offices of the Ciguri, Gruber, deeply troubled, sets off in search of something... somewhere... doesn’t matter where. In fact, he doesn’t know what he’s doing—but in the next panel he’s looking in the window of a second-hand bookstore.

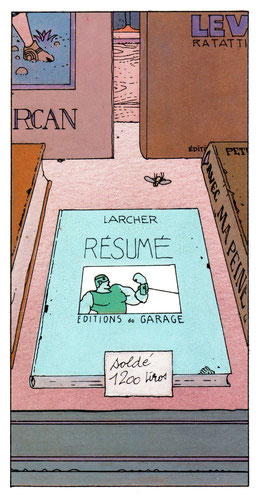

The book that catches his attention is a slightly worn copy of RÉSUMÉ, published by EDITIONS du GARAGE. The “résumé” is the device that recapped preceding chapters in the original serial, or teased the reader by making jokes instead, or introduced new information. The illustration on the cover features the archer, who first appeared in episode 11 of the Garage, in a pose that recalls his final appearance in episode 32. The author of the book is named Larcher (l’archer). Those who might be amused by such details are invited to notice that a fly lies dead, several inches from the book.

The first two pages of RÉSUMÉ form pages 9 and 10 of L’Homme du Ciguri. They are the first two pages (re-drawn, with rather more deliberate care) of the Garage.

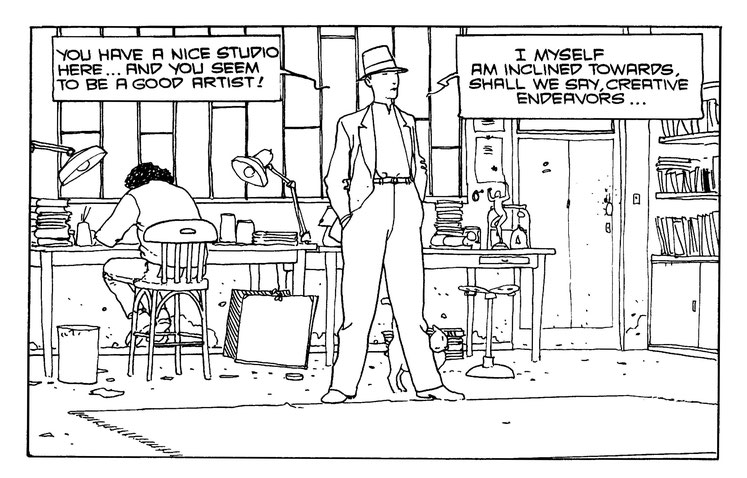

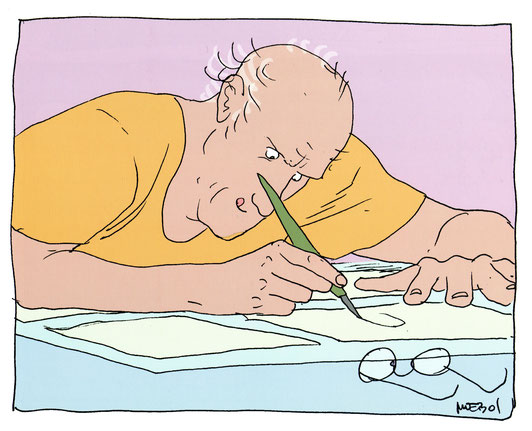

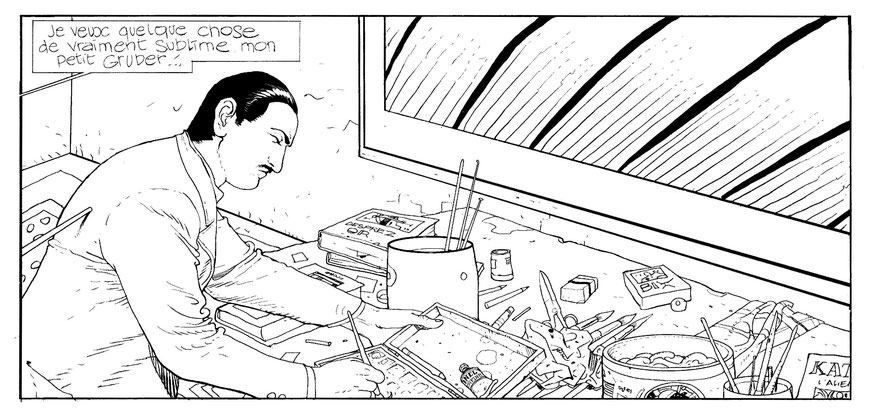

Is there any danger Gruber may read so far that he’ll begin reading about how he began reading the book he’s now reading? Not impossible, but surely that belongs to the sequel. Anyway, his reading will be interrupted. In the meantime, on pages 11 and 12, he turns the pages slowly—though he quickly resolves to find the author/artist, whose first name is given as “John”. On pages 25 and 26, at the halfway point of L’Homme du Ciguri, Gruber enters the artist’s studio where he finds the artist at work.

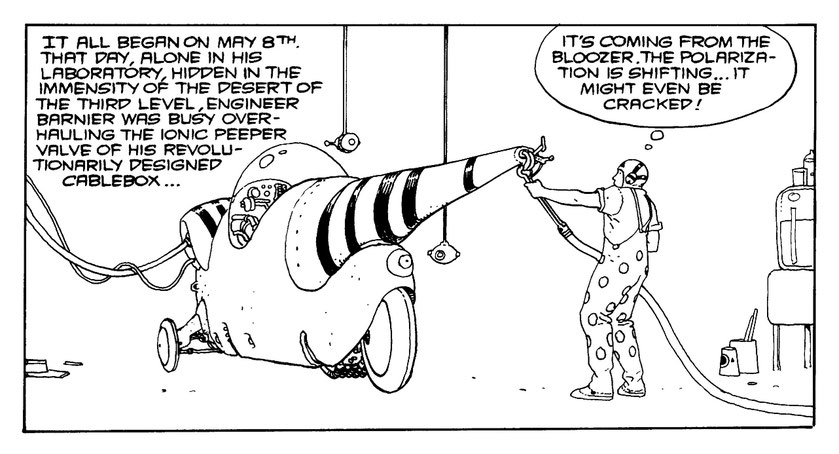

It’s no great secret who Larcher is. RÉSUMÉ opens with the words ,“iT ALL BEGAN ON MAY 8”—Giraud’s birthday. Gruber is reading Larcher’s book in a café in Fontenay-sous-Bois (see p.19)—where Giraud grew up and lived for many years. But though he appears, in part, in a half-dozen panels between pages 26 and 32, the artist never turns around, never speaks, never stops drawing. Gruber asks about a large picture on the wall, depicting a scene from episodes 18 and 19 of the Garage, but the artist’s female companion, Marie-Laure, says, “LEAVE HiM iN PEACE !.. WHEN HE’S LiKE THAT, THERE’S NOTHiNG TO BE DONE !..”

“YOU MEAN TO SAY HE ENTERS A SORT OF TRANCE? ” asks Gruber.

Call it by that name if you please. Giraud certainly did, more than once. He drew habitually, perhaps compulsively. He related more than once how, as a child, he’d drawn as a means of coping with the separation of his parents: “I was responding... to an imperious need to send out communicating signals at a time when I spoke with difficulty [and] was plunged into inexpressible confusion...” (histoire p.25). Drawing became his work, but he also drew to relax, and never forgot that his career had its foundation in childhood:

Drawing is a childish activity. To spend one’s life drawing is a real challenge... The very fact of following this profession seems to me transgressive.

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double p.15)

Characteristic of his work as Mœbius was its spontaneous character, and if the act of drawing constituted the world of the Garage and its story, it’s a creative act implicated, self-consciously, in the sequel—and in every further development of Gruber’s adventures. In Le Major, in a sequence of pages (155-163) drawn in 2001, Gruber begins decorating the walls of the corridors of his private retreat. More than two decades earlier, Osborn Fildegar similarly decorated the corridors of his spaceship in Tueur de Monde, drawn as Giraud was leaving the Garage behind. Fildegar might be read as an artist in search of a new direction, and breaking with the past, but he also refigured Giraud’s earlier rebirth as Mœbius. Behind Mœbius lay a nameless impulse or necessity, open to successive incarnations—indeed, to being incarnated in successive panels—but Giraud’s conception of art, and his self-conception as an artist, also embraced this turning back upon himself:

As the truth of autobiography consists of more than dates, the truth of creation is not in the time of execution... Art’s childhood is the forgetting of time. In the same way it is perfectly correct to claim an artist constantly repeats the same work, the same theme, to infinity. Where’s the problem? Isn’t every human action the repetition of an original, foundational act?

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double pp.15-16)

Le Major also repeats the plunge toward the desert of “Absoluten Calfeutrail”, and further extends a playful means of evoking psychic plasticity (as bodily transformation and extension) explored in “Éscale sur Pharagonescia”. These elements are found again in Inside Mœbius, where the artist and the act of spontaneous creation take center stage, while Gruber plays the (frequently comic) supporting role of character-in-waiting.

He waited while Giraud, among other things, amused himself with Inside and patiently constructed an open end and new beginning for Blueberry; but at last Giraud found a way to resolve a plot in which Gruber had become embroiled back in 1998 and 1999.

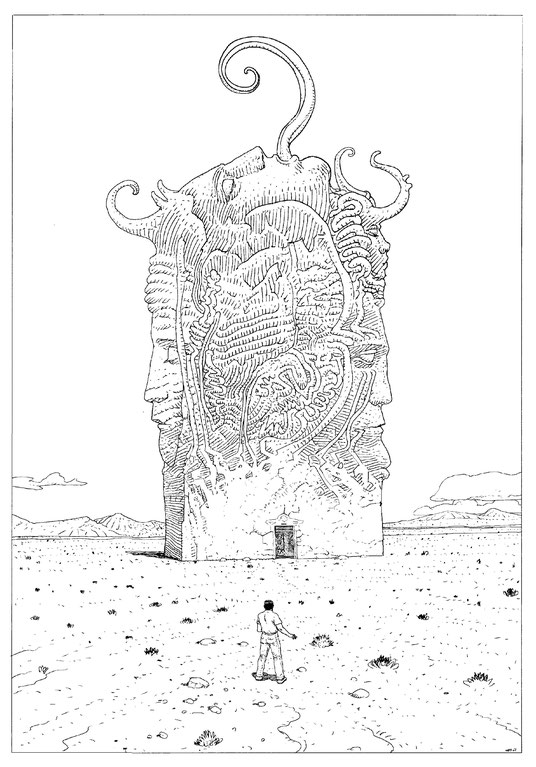

In 2007, Giraud incorporated an image he’d made four years earlier in what would become the thirty-fifth page of Le Chasseur Déprime. Modified, this became on the following page a structure with an open doorway—which turned out to be a museum, hung with pictures. Gruber entered. It’s a device that may have taken its lead from Giraud’s playful collaboration with Stéphane Cattaneo, Beautiful Life (2004).

With Ciguri, Giraud sought to carry on the Garage in time, not only by picking up where it left off, but by reproducing the rhythm of its serial production. It ultimately broke down, trailing into inconclusiveness. Chasseur picked up elsewhere, and was pieced together over the course of a decade. Its variable texture and visible dates everywhere expose traces of its prolonged but non-sequential gestation. Freed from serial production, the time of its making is distributed across the space of the narrative. To follow the story is to wander in time. Like the museum into which the story invites Gruber, the story itself is a retrospective exhibition of Giraud’s work; but the act of looking is at last implicated in a plot of seduction and malign enchantment. Gruber, first a spectator, becomes a custodian of these images, then must make the work of art in which he will finally be lost.

Is there no escape?