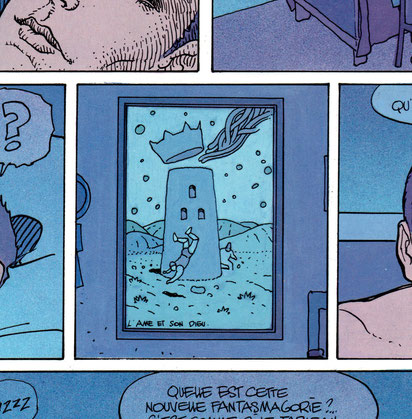

36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

17: Is there anybody out there?

In the beginning, comics possessed a transgressive virtue: no one regarded them. That suited me perfectly. I found in that situation a true liberty... Recognition has come little by little. We can’t say comics are perfectly established, which is not displeasing. It’s the price of a certain liberty, even if it sometimes causes a slight feeling of frustration. Like all creative activity, comics would like to enjoy a full and complete recognition of what they are: a mature medium of expression. But perhaps we don’t yet deserve it? ... Society leaves us on the margins: a kind of logical form of social darwinism.

The medium of comics, then, hasn’t really chosen secrecy: it’s nothing but a passing phase. Therefore, little by little, I have developed my own marginality...

(Giraud, Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double pp.170-1)

Of interviews with Giraud that I’ve read, possibly the most interesting—certainly with respect to the Garage—is a conversation recorded by Lewis Trondheim in 1995. The conversation was published in Le Lezard #11, January 1996. (I found it in French here.) It was nearly two decades since the original serial’s tentative beginning in Metal Hurlant, and among questions Trondheim wanted to ask was: what did Giraud do when people told him the Garage was a unique work, complete in itself, and that he had no right to make a sequel?

A quarter of a century later, Trondheim’s question suggests that when that sequel, L’Homme du Ciguri, was published in France, it was a plausible if not necessarily prevailing opinion among fans and critics that Giraud’s major work as Mœbius was a thing of the past—much-admired, but a museum piece. And Giraud acknowledged that Ciguri was

the somewhat bitter confirmation that one can’t reproduce this same miracle twice. In Le Garage Hermétique, it’s not so much the story that counts as the relation established between the artist and the reader in the precise context of the magazine. L’Homme du Ciguri doesn’t benefit from such a clear relational context—Le Garage demanded more than two years of monthly publication, a drop at a time, two years on the razor’s edge...

To be clear, the original serial appeared over thirty-six successive issues, beginning in Metal Hurlant #6, which was bi-monthly at the time. With issue #9, as the fourth episode appeared, the magazine became a monthly. Metal Hurlant, in the seventies, was on the cutting edge of the contemporary explosion of science-fiction and fantasy into the mainstream; but the comic book in which the sequel made its first appearance—Dark Horse’s Cheval Noir—was a rather more marginal affair, offering to the North American market an anthology of European and Japanese works. Even so,

It was tempting: a publication in black and white, with the same rhythm and the same liberty as in the time of Metal. I accepted, and was able to supply two or three pages a month for nearly a year and a half... And then the source dried up for practical reasons and the project wasn’t finished...

I’m not sure to what practical reasons Giraud was referring, but The Man from the Ciguri didn’t appear in every successive issue of Cheval Noir, so the urgent rhythm of the original was not maintained. Giraud, as one of the founders of Metal Hurlant, had a commitment to (and financial stake in) the magazine to which he supplied installments of the Garage; not so with the sequel. And when Cheval Noir was cancelled with its fiftieth issue, the follow-up to the Garage hadn’t reached a conclusion.

By the time L’Homme du Ciguri appeared in French, it was already something that had faltered and failed. Metal Hurlant had ceased publication back in 1987, and Giraud was disappointed not to find a magazine in France willing to publish the sequel as a serial before it appeared as an album. “Sometimes,” said Giraud, “I overestimate the appeal of my work.” Moreover, the album was not as he’d envisioned it:

it must be noted that the album came out in color and on fifty pages, whereas I would have had it in black and white, on a hundred pages...

So it appears Giraud, too, had reason to be at least half-persuaded that he, along with the magnum opus of Mœbius, was somehow stranded and out of his time:

All one can hope is to catch a distant echo, now fifteen years old, and well encysted in our memories, nearly mummified...

But why should an artist relinquish the work it is given him to do?—the work that offers him the opportunity to grow and to fulfil himself. Giraud also said something that indicated he was not yet finished with the Major:

I have the impression, sometimes, of making a kind of long “issue”, over thirty years, before a patient and faithful public persuaded that it’ll end by getting something from all this. (Either it’ll end by crashing definitively, or it’ll take off into the blue of the sky, or... Nothing but a gesture!)

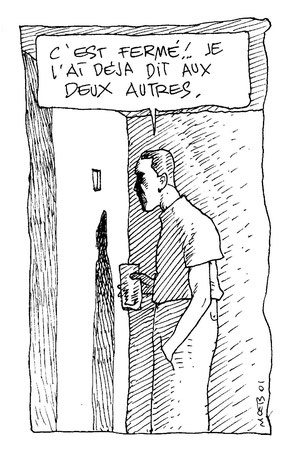

Later in the conversation, Trondheim pressed Giraud on his responsibility for the form the album had taken, complaining that if Mister Blueberry and L’Homme du Ciguri came out at the same time, and the latter cost twice as much as the former, it might seem Giraud was subsidising the publishers of the latter (Les Humanoïdes Associés). Trondheim suggested Giraud might also thereby cut himself off from one part of his public. Giraud made the interesting, and perhaps also revealing and prescient observation that he was well content to cut himself off from part of his potential audience: “J’aime bien me couper d’une part du public.”

True to his word, the adventures of the Major (as far as I can tell) were never again presented before a broad public, but only to those among his fans who were patient, faithful, and paying attention.

I wasn’t one of them. I’d fallen by the wayside round about the time Giraud started doing The Incal with Jodorowsky, and—notwithstanding the fact I bought Marvel’s edition of the Garage and read some Blueberry at the end of the eighties—he never got me back. So I was rather startled, when I started playing catch-up, to discover just how private the Major’s adventures had become.

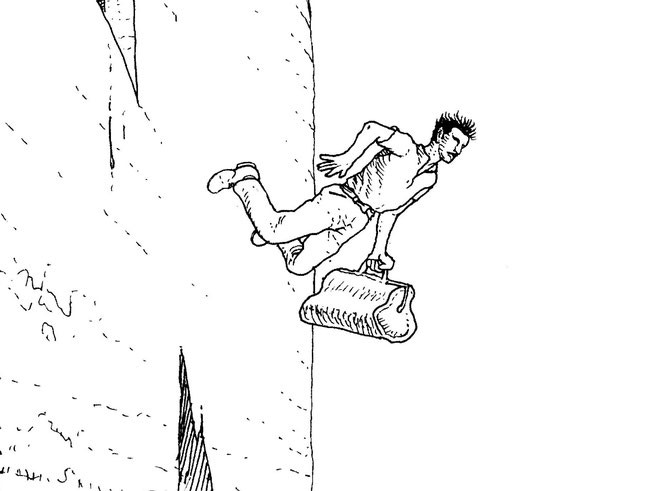

Gruber (no longer Grubert in French) did play a significant if secondary role in Inside Mœbius, the six-book series published by Giraud’s own publishing company, Stardom, between 2004 and 2010. The Major’s third freestanding adventure, Le Chasseur Déprime, appeared with little fanfare in 2008, also published by Stardom. And in 2011, the year before Giraud’s death, the eccentric, reclusive years spent by the Major in Giraud’s private notebooks were published as Le Major—in an edition of only 1000 copies.

The latter volume has since been reprinted in an edition of 3000 copies—and (like Le Chasseur Déprime) has also been translated into Spanish—but it still seems an astonishingly small number. I’ve no idea what the print run on Heavy Metal was when I began reading it back in the seventies, but I had no sense then that I was doing anything other than supping at the font of mass culture. The Garage itself has been in print, in French, for forty years. Yet if there are only 4000 copies of Le Major in its original language, and copies of the second edition are still on sale, it rather looks as if readers are coming to it one by one. When I open its pages, I don’t feel I’m sitting in a crowd; and—faithless reader that I am, returning to Giraud after three decades of indifference—I find myself wondering how it falls to me to be reading this, and taking delight in it.

I’m sure others are reading it, but for me it feels like a very personal encounter because, if finding Inside Mœbius was a happy accident (and yes, I know Giraud was disinclined to believe in accidents) nevertheless I discovered Le Major because I’d started looking for something. It wasn’t under my nose, I didn’t have the opportunity to examine it before buying it; and then I had to accept that what I was buying was in a language I don’t understand easily. At every stage, I had to make a decision, take a deliberate step. And even when the book was in my hands, I was in equal measure pleased and uncertain.

Does this matter? Let me for a moment ignore the metaphysics of fate and ask: is this just an accident of circumstance? Is it my own perspective, my own history as a reader that makes it all seem surprising? Or is it that when the Major—along with “Mœbius”—moved out of the mainstream, toward self-published and limited editions, Giraud was resetting his relation, or sense of relation, with those interested in the part of his work that was always (if not always so clearly) the most recondite and most personal?

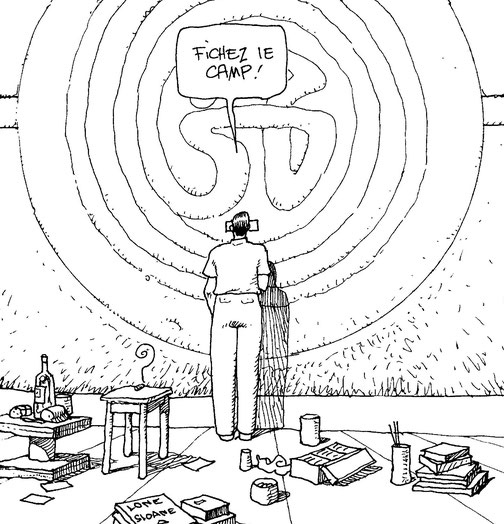

Artists and their admirers are doomed to be separated by the very things that bring them together. Sometimes art is just the making of a thing to be admired; but it can also be an act of communication richer and more successful than anything that can be achieved face to face. Yet, paradoxically, it is also bound to fail. Whatever an artist brings, by way of personal expression, to a work of art, and with whatever sympathy I, as a member of the audience, approach, the medium and the formal qualities of the work constitute a maze in which we are lost to one another.

Life is short, art is long. After forty years, I recognize that, behind some of the pages I admire, stands someone I don’t know. In later work, he began waving. He wasn’t waving to me, because he couldn’t see me; but, however private the impulse to work and however personal the procedure, Giraud worked (as, I suspect, many artists work) in relation to an imagined and problematic audience. As he told Trondheim:

Le Garage Hermétique is a good example of an attempt at controlled madness... It was at the limit, but it was controlled... Beyond this limit, I skidded out of touch with the reader... It must not be forgetten that true madness... which exceeds limits, is a human drama... It’s also a natural function, delirium permits a form of expression nearly beyond language, but also a call for help, also a prison...

... Neither must it be forgotten that we are jugglers, that we’re trying to attract the largest crowd possible into our small personal circus, and we’re ready to do anything to seduce passers-by, we’re ready to do anything to be recognized by our “family”, our survival’s at stake... And what’s inside the circus? Our needs, our wishes, our hates, our loves, and all our magic tricks tricks that render them useful and interesting...

The main thing is to know whether we’re working with or without a net... We need to survive at the end of each show, at least...

... The artist is therefore “happily” condemned to a crazy vaulting between a “sincere” expression of his madness and the cynical management of practice and technique...

Yes, the Garage is a good example of the marriage of madness and technique.