36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

18: The art of picture stories

One can push the relationship with the public to its limits in terms of intimacy, but no further. It’s like if you were whispering on stage, it’s more difficult than doing slapstick. But they’ve got to believe you, otherwise you fall flat on your face...

(“Interview with Moebius”, dustwrapper of Graphitti’s Mœbius 4)

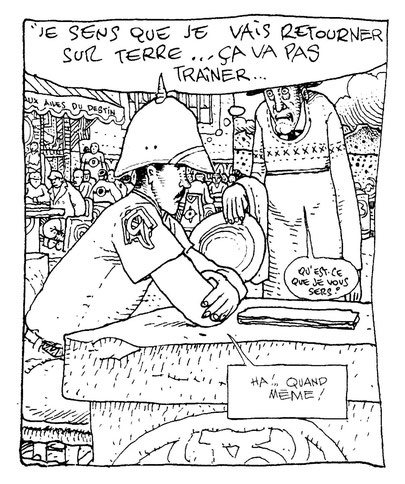

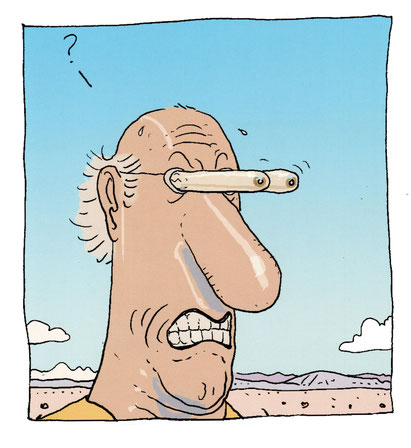

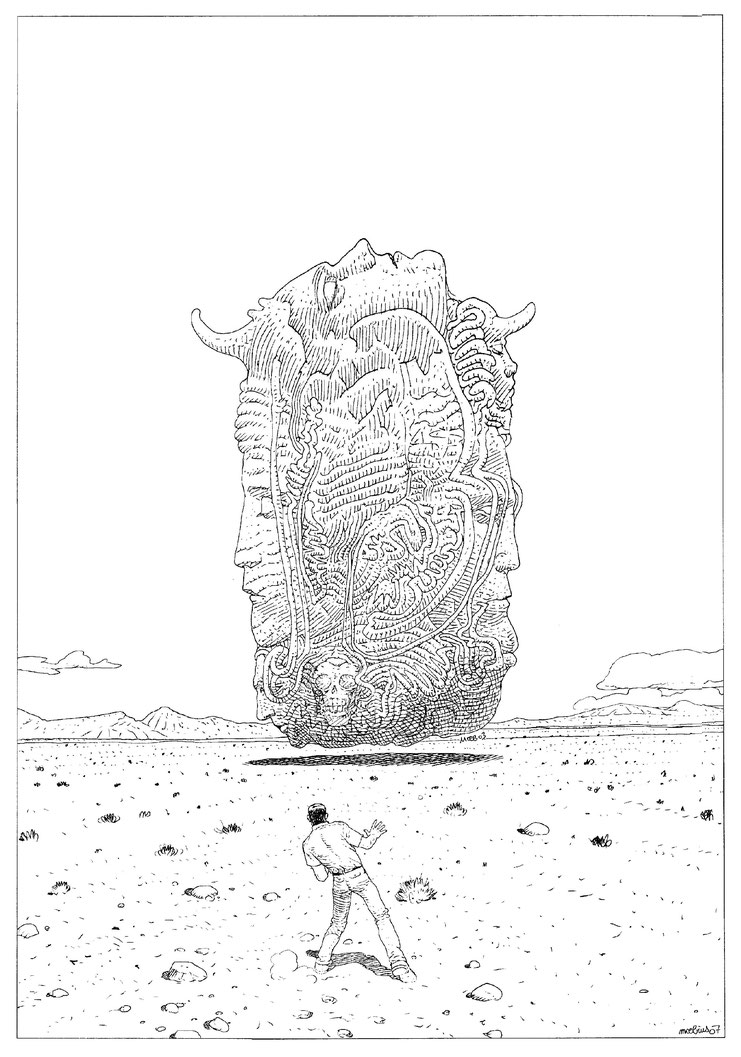

There’s a panel in Le Chasseur Déprime that brings a smile to my face. Gruber has taken a seat at a table, and is waiting to be served. At last, a waiter arrives to take his order. About time. As the waiter leans forward, I see that his hand is a slab, with a rude fold of cartoon fingers depending from it. Looking at this, I smile.

This pleases me. It suggests that, after all these years, I’ve arrived at some kind of a balance in my response to Giraud’s work.

It may seem a curious thing to say, but I’ve been almost embarrassed, over the past couple of years, to find myself taking delight in Giraud’s art. Embarrassed, and mildly troubled. They are two separate things.

My embarrassment has been closely allied to admiration—which followed closely on the immediacy of pleasure I felt, looking at images so poised, light, spacious, and sure of themselves. Giraud’s mastery of drawing is as evident in sketches and cartoons as in some of his more fully realized work; and some small pictorial shortcuts and a characteristic inconstancy are not so much flaws as they are the hallmarks of a very personal elasticity of style.

But as I looked at some panels in the Garage, and felt the force of my response untarnished by the decades; as I sank into panels of The Man from the Ciguri, of which I’d seen little until last year; as I admired, in Stel, what I think are some of Giraud’s most persuasive science-fiction pages, I found myself wondering: is this all it comes down to? Is Giraud just better at drawing than anybody else?

And this ridiculous suspicion embarrassed me, not least because it seemed a betrayal of some of my favorite comic book artists, whose technical capacity is—how shall I put it?—not so pronounced.

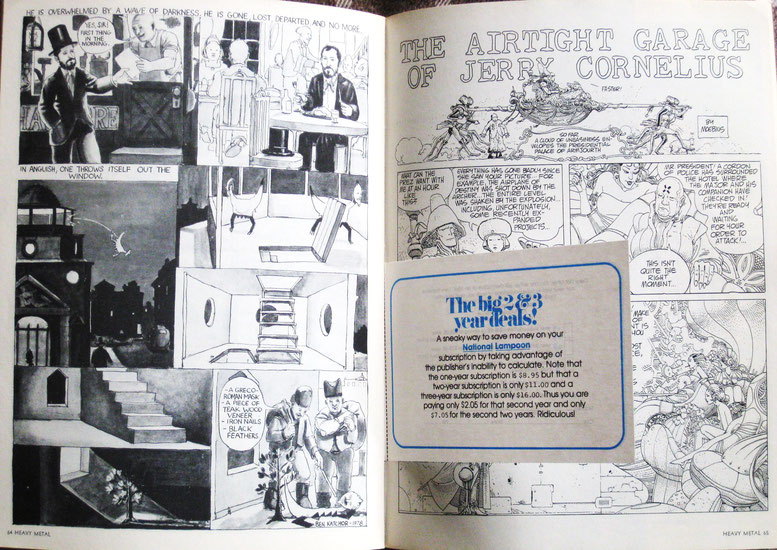

As it happens, I first saw Ben Katchor’s work nestling against Giraud’s, in the pages of Heavy Metal. He hadn’t quite settled into that distinctive style—halfway between cartooning and sketching—that cosseted Julius Knipl’s perambulations through the architectural and commercial byways of New York, but he was on his way. As I saw further work in early issues of RAW, my initial curiosity turned into a settled partisanship. Of course, nobody ever listened to me, so I have to admit that Katchor has jacked himself into the pantheon by dint of hard work, persistence, and by impressing other people too.

And, while I’m on the subject, if you find either my long-windedness or my tendency to ramble irritating, you can blame Ben Katchor. (I know I do.) Not because he had any influence on the way I write, but because, having been hugely impressed by his story, “The Printer’s Disease” (Picture Story #2), I then went on to read—and, more importantly, to think about—a story by Basil Wolverton in a way that, otherwise, I might not have. And if I hadn’t thought it worth trying to write about Basil Wolverton thirty-odd years ago, I might well have lost touch with comics altogether, and probably wouldn’t be writing this now.

I know: and the world would be a better place. If that’s how you feel, the door is over there.

Basil Wolverton is an artist whose influence is perhaps hard to quantify, but when Harvey Kurtzman put one of his illustrations on the cover of MAD #11, it was a bolt of lightning that instilled life into a generation of cartoonists who, more than a decade later, would infest the underground comics. I was eleven or twelve when a subsequent bolt of lightning (“Meet Miss Potgold”, from MAD #17) fried my circuits and prepared my way to becoming a lifelong fan.

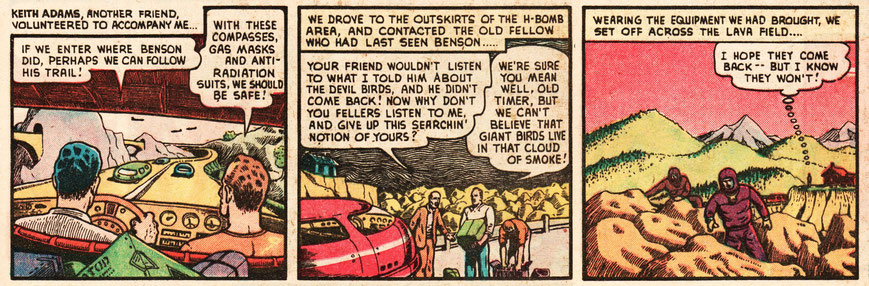

Wolverton and his work have turned me upside down and inside out several times since then, but it took me a surprisingly long time to figure out that what I found most effective in his sf stories of the fifties—the distillation to a pictorial essence of narrative—resulted as much from his limitations as an artist as from the refinement, over two decades, of his storytelling. Though he’d developed a polished cartoon style in his humorous strips, his sf depended on a grasp of anatomy and perspective that were never more than approximate.

If it were simply a matter of talent and/or ability, I’d be obliged to admit that Wolverton’s achievement dwindles into insignificance when placed against Giraud’s. But the world I live in is messier than that. Even if Giraud, like Wolverton, secured a place in my attention by the initial impact of a handful of images, and even if his work, years later, repays my attention richly, as Wolverton’s has done, nothing by Giraud has ever had, for me, the concentrated seismic impact of my reading of Wolverton’s “the Devil Birds”. And no, I wasn’t eleven or twelve when I read that.

Of course, they’re very different artists, and an attempt to measure one against the other would probably be as tendentious as the connections between them are tenuous. Both were readers of sf, both produced comic book stories grounded by their reading in sf. Wolverton was published in MAD, by which Giraud was influenced. Giraud was also later inspired by the freedom of the underground comix, many of whose artists acknowledged the impact of Wolverton’s work (while extending and exaggerating his transgressions against good taste). It doesn’t amount to much.

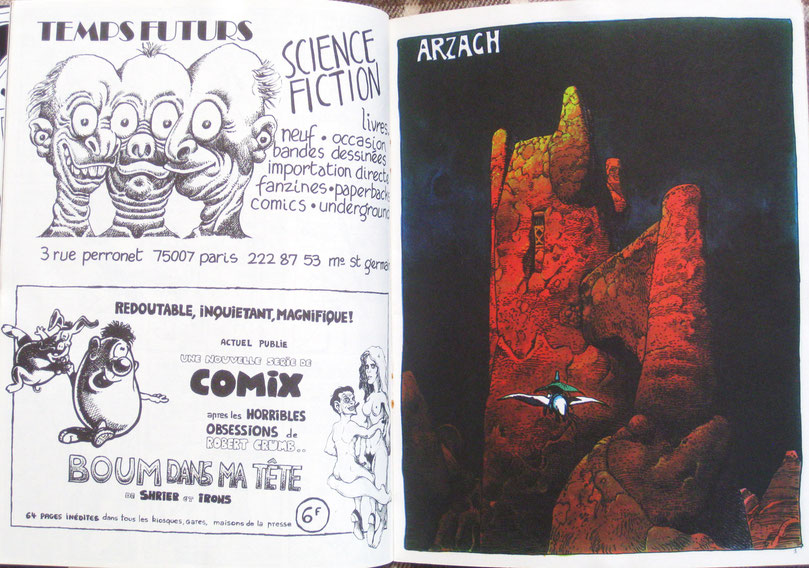

On the other hand, I was surprised and amused to discover, last year, that Wolverton was represented in the very first issue of Metal Hurlant, at the beginning of 1975. Among the ads in that issue was a half-page for a bookshop (Temps Futur) using a swipe from a cartoon Wolverton had drawn for Glenn Bray. It featured three conjoined heads sharing four eyes. And what, on the facing page, were those four eyes staring at? The opening panel of the first “Arzach”.

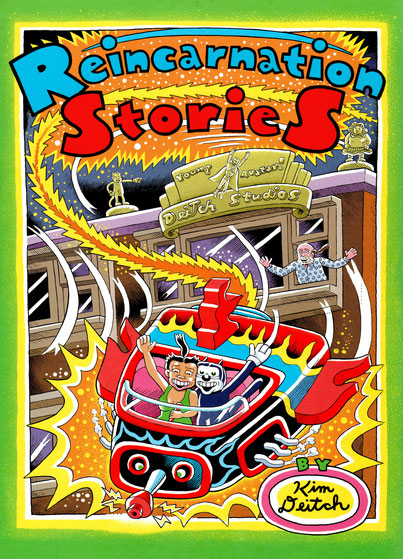

Wolverton isn’t the only artist whose work, despite obvious and admitted limitations, has continued to pop and fizz in my consciousness for a half-century. Another is Kim Deitch, who saw Wolverton’s work in MAD when it was first published, and, nearly two decades later, was pleased to share space with him in Comix Book. Though both artists refined their limited natural talent in order to arrive at a unique, idiosyncratic and unmistakeable style, there the resemblance ends. I was as appalled as I was fascinated by the crudity of Deitch’s stiff, squared-off characters when I first saw them, but when I fell in love with his cover for Laugh in the Dark, I began to shed my reservations. Doesn’t mean I’m bound to overlook the fact he’s had his off-days, but he’s come up with the goods often enough that I’m grateful he’s been able to keep doing what he does for as long as he has. My world’s been a better place for having Kim Deitch in it.

And Deitch—if he hasn’t quite left me listening intently to the silence, as Katchor once did, or humming internally and almost weightless, as Wolverton once did—has more than once bubbled up from under me with an effervescence that left me dizzy but refreshed. He’s produced pages I can’t help but look at with astonishment, not least because his style, by now so familiar, still teases my eye with the suspicion that it might actually be unassimilable—often bold and decorative, yes, but potentially opaque and... unreadable?

Yet, therein lies my astonishment: into that cartoon hall of mirrors I’ve been drawn, and found it alive. Not only is it alive, but its idiosyncrasy has become so transparently personal that when I got my hands on his latest book, Reincarnation Stories, it felt like reading a letter from one old fart to another. Thanks, I’m doing ok, too. Great to hear from you, Kim. Write soon.

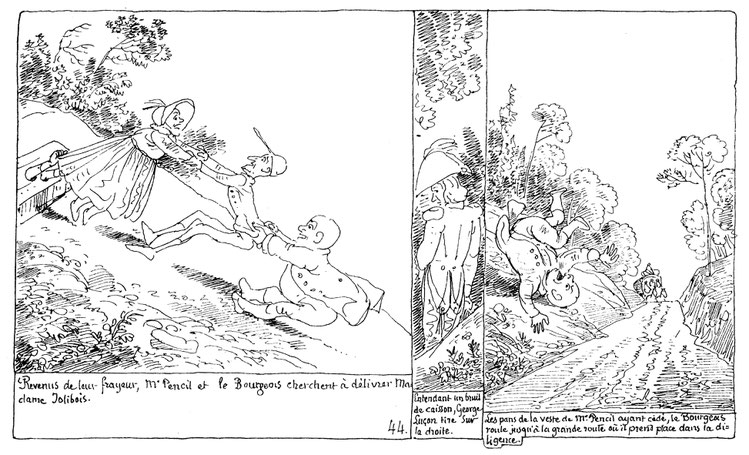

Now, my reason for bringing together these four dissimilar artists—Wolverton, Giraud, Deitch and Katchor—is simply to remind myself what ought to be obvious: that while the success of a comic strip may be impaired if it’s badly drawn, its success doesn’t depend on how well it’s drawn. Pictorial and narrative elements are co-dependant, and that co-dependancy allows for considerable latitude in what may be accounted the success of a comic strip. In 1837, Rodolphe Töpffer—who may have been the first theorist of the picture story as well as, near as dammit, the first modern cartoonist—wrote, in reference to his work, M. Jabot:

This little book is of a mixed nature... The drawings, without the text, would have only an obscure meaning; the text, without the drawings, would mean nothing... If the author is an artist, he draws badly, but he has some idea how to write; if he’s a writer, he writes poorly, but on the other hand he has, in terms of drawing, a pleasing amateur talent...

But, if the co-dependancy and collaboration of word and image is so obvious, and was recognized so long ago, why do I need to remind myself of it? Why was I embarrassed, and troubled, by my response to Giraud’s work?

Well, over the years, I’ve also become aware that, faced by a comic book page, many people form a judgment based entirely on how it looks, not on how it can be read. Sure, there were artists and art styles I never warmed to, but that the success of a graphic narrative might take a wide variety of forms I took for granted. Yet, looking again at Giraud’s work, I find in myself a measure of prejudice and false judgment that appear to contradict this finely balanced open-mindedness.

To put it simply, when I first saw it, I was impressed by Giraud’s art. No great surprise. I wasn’t the only one. But, on recollection, I also know I preferred—and it may be fair to say I still prefer—his more detailed and carefully rendered work. I remember I enjoyed “Shore Leave” when I read it in Heavy Metal, but I think if you’d asked me then, I’d have said it wasn’t one of his best, because I know I regretted that it was visually lighter, more whimsical, more cartoonish than some of his other efforts. I failed to recognize that it was arguably the most fully realized sf short story he’d done up to that point. My response was informed by an awareness of what a Mœbius story could be, but undermined, in part, by a no more than half-conscious prejudice in respect of what it ought to be.

Nearly four decades later, when the first volume of Dark Horse’s Inside Mœbius returned me to Giraud’s work, I was immediately charmed, I enjoyed it immensely—yet I’m aware I also regretted, to some extent, that it wasn’t executed with more refinement, that it wasn’t the kind of thing that had most impressed me first time round. Some essential aspect of my experience of Mœbius had been pictorial. Reading the first part of Inside, I found myself wanting to be astonished by the pictures; but, for all that the compositions and narrative flow were typically assured, the rendering mostly lacked the precision and weight to be imposing.

Giraud was aware of my expectation before I was, and made light of it. (He also introduced more precision and more polish as the series went on, and I don’t regret that he did.) But as I re-acquainted myself with his work, and made the acquaintance of works from over four decades that I’d never seen, I became more aware of how much a momentary and free variability of approach was essential to Giraud’s work as Mœbius. If I regretted that comic strip B wasn’t the same kind of thing as comic strip A, this reflected my preferences; but where I supposed A might have set a standard for B, I was in error—and essentially out of sympathy with the artist.

My attitude, and my way of looking at these stories, has certainly changed; and my reading of the more oblique “sequels” to the Garage has played its part in bringing about this change. I had my doubts, for instance, about Le Major, and not just because it was in French, which meant I’d have to do a bit of work in order to read it. I think I was undecided about the status of something that had taken form in Giraud’s private notebooks. I’ve never been very interested in looking at sketches or sketchbooks, so I suppose I wondered: is it a real story? Does it bear a genuine relation to the Garage, or is it just some doodling the artist did to amuse himself? Is it something too private to be of interest?

Also, unlike the Garage, unlike Ciguri—and unlike Le Chasseur Déprime, which I hadn’t seen at that point—Le Major wasn’t a story developed on full-sized magazine pages. Some of my longstanding associations with comics in a smaller book form are based on reprints that were readable, but broke up the integrity of the original page. On the other hand, I was reconciled to the small paperback format of Harvey Kurtzman’s Jungle Book, and it was Giraud’s choice to draw these meditations on Gruber’s retreat from public life in a small notebook. So what’s my problem?

No problem, really. I’m just rather a timid reader, sometimes.

But if Le Major didn’t go out of its way to reassure me concerning its intentions, and if the first two chapters met my hesitation with a rather opaque uncertainty of their own, I’ve nevertheless found it a work that opens rather generously to a conversational interest. Even if it’s more recondite and self-regarding than the more widely published parts of the Garage, it also serves as a revelation (like Inside, but perhaps more intimately) that the public face of Mœbius was always an inversion of the private face of Giraud. Back in 1988, Giraud told Jean-Marc Lofficier that

An artist is by nature someone very sensitive, who expresses with talent the pains that he suffered. He uses art to replace the communication that he didn’t, or doesn’t, have with others. Most artists were sensitive children, often introverted, and suddenly they discover that there is a very big demand for that very same expression of their sensitivity. They discover that, in our harsh world, there’s a small oasis for dream makers, and you even get paid for it.

(“Interview with Moebius”, Graphitti's Mœbius 5)

Read as a generalization regarding artists, that may sound bland and platitudinous, but as a personal statement of Giraud’s own situation, it perhaps allows a narrow shaft of light to fall on the heart of the mystery. When he drew himself sitting with his back turned in The Man from the Ciguri, was the artist simply toying with the Major? Or was it that Giraud himself was not yet ready to turn and speak directly in the face of his audience.

Ironically, Giraud’s adventure as Mœbius had opened, in “La Deviation”, with self-portraiture. Not long afterward, he drew himself answering questions posed by interviewer Numa Sadoul. But fantasy, in the first case, and sarcasm, in the second, kept the reader at a distance. Inside Mœbius inverted the situation: though not exactly a work of self-revelation, one may find within the fantasy and helter-skelter of gags within gags an opportunity to come as close to the artist—in his art, if not in person—as one is willing to go. I think it’s less opaque than it first appears; and, by insisting at all times on its moment-to-moment creation, Giraud encouraged me, first of all, to attend to each page as though anything might happen on the pages to follow; and, secondly, to accept that although all is now inscribed in history, with the force of an apparent inevitability, it remained possible to return to his earlier work and see it for what it was—an expressive effort responsive to the trembling and dubious moment that gave it life.

Le Major brings the adventure full circle. In Inside, whose beginning was entirely private, Giraud simply began to speak, shaping as he went along the comic book self-representation that allowed him to speak about his situation as an artist and speak with his creations. In Le Major, by contrast, the silence of the creator reigns until Gruber is driven to prise Giraud’s self-representing character out of hiding. It’s a confrontation with reality that at once echoes and inverts the ending of the original Garage, yet it turns upon itself and offers a further twist. Le Major transports Gruber to an enclosed region of restriction and regret, but finds its way, at last, to becoming the genuine, mysterious and moving end of his odd, expanded, but always unstable and fragmentary adventures.

Le Chasseur Déprime was finished and published before Le Major, but for much of their period of gestation, they were contemporaries. Chasseur is an episode not quite self-contained—essentially complete, yet open-ended—and, yes, I look at it and wish I might immediately, or next month, or next year, begin reading the next story in the series, continuous with this one. But the hermetic garage, whether we consider it finished or unfinished, doesn’t work that way. Indeed, it may appear (if we discount the uncollected chapters of Ciguri) that the end of each book is the same, always the same: a man passes through a doorway, in order to enter another world. Only Ciguri is directly continuous with the preceding part, however; while Le Major turns at its close, oroubouros-like, toward the beginning, in order to cut off the tail-eating head. In Chasseur it’s not exactly a doorway.

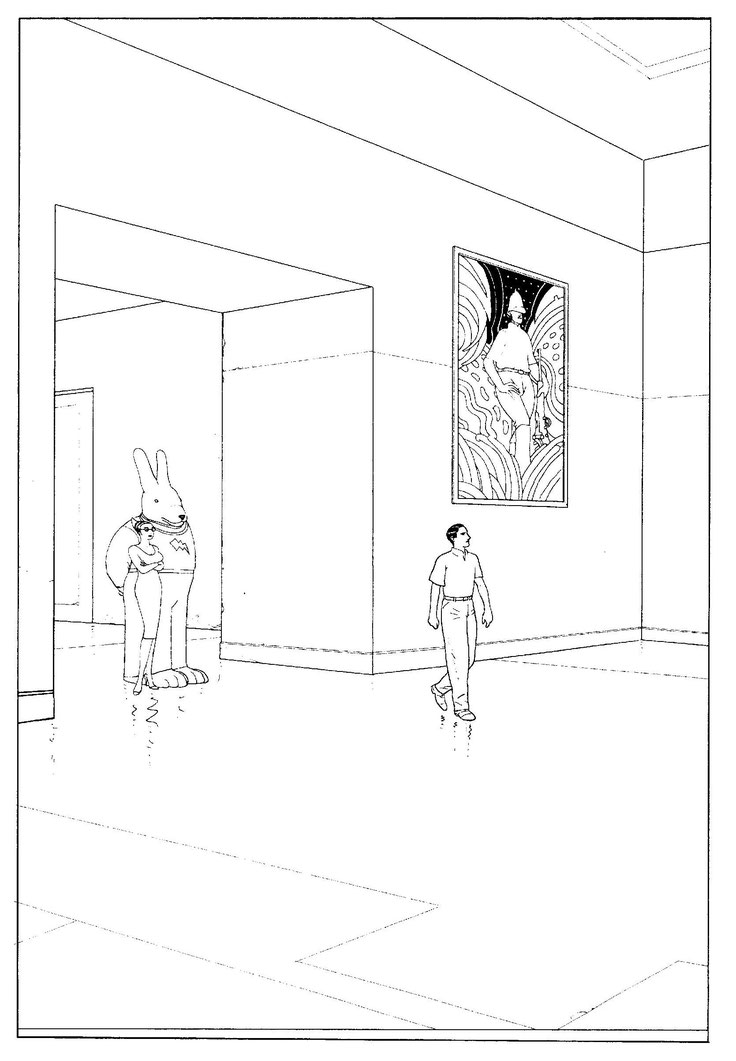

The first Garage was a linear, episodic production of nearly a hundred pages, with more than a handful of focal characters, constructed on the installment plan, continuously, over a period of three years. Chasseur presents a remarkable contrast: not much more than half as long, it rarely allows Gruber to stray from the reader’s attention, and was completed over a period of more than a decade. Time is visible in its pages: the first three are dated 2007, but the fourth (numbered page 2) is dated 1998. Thereafter, from page to page and panel to panel, the art pursues a wayward course through the years. The tenth page leads off with a panel from 1998 (it formed originally part of the previous page, numbered 6) and ends with a sequence of panels dated 2005. The two panels on the seventeenth page are dated 2006 and 2008, while the top half of the following page is a panel from 1999. The opening into Gruber’s second and third dreams feature illustrations dated 1996; and images dated 2005 grace the walls of a museum in panels drawn in 2007. The museum itself has its origin in an image from 2003 that’s incorporated into a page dated 2007:

Chasseur was published in 2008 as a handsome, soft-covered comic album, on pages a little larger than those devoted to the original Garage. About a quarter of the story’s fifty-two pages consist of full-page single panels, and there are almost as many panels that fill a half-page or more. There’s no question it’s a story to be looked at as much as read; but if the story develops with a leisurely and deliberate tread, the resolution of the art varies almost continuously: cartooning jostles with illustration, delicate detail with sketchiness, clear lines with shading, thick lines with thin, hand-drawn borders with ruled borders, careful with casual lettering. In the original Garage, variability of style was largely compartmentalised, within individual chapters; in Chasseur, successive pages and successive panels display the quilted patchwork of the times and varied manner of their making.

The effect is lively, but I’ll admit that when I began reading I was a little disconcerted. (Not more disconcerted, perhaps, than when I saw the original Garage for the first time, forty years ago.) Whimsical details abound. The costumes of characters mutate from panel to panel, and the Major even gets a devilish pair of horns for his helmet in one panel on the fourteenth page. Is it really possible that, as I settled into the story, succumbing (with no great effort) to its enchantment, I yet entertained a tiny, unarticulated wish that Giraud might stop his fooling and play it straight?

Yes. But, after all, I’m sometimes surprised to look in the mirror and see a po-faced clod looking back at me. I was also surprised, on the fourth page, to see, in the space between the hand-drawn borders of the first two panels, a little cartoon bug named Marcel stepping out to introduce himself. Did I greet him initially with pleasure? Or was I a little embarrassed?

Reading the story a second time, I’m less reserved.

Oui, c’est Marcel. Bonjour!

And when, at last, later on the same page, the waiter arrives to take the Major’s order, I smile when I see the waiter’s hand, because, whatever the remembered magic of the odd worlds of Mœbius to which I was introduced back in the nineteen-seventies, and whatever my old prejudices regarding the conduct of fantasy, it’s clear that I’ve learned to recognize and to accept Giraud as a cartoonist—as someone whose art and story are flexibly and often playfully bound together. Chasseur is an autograph work, a sketchbook, a portfolio, an adventure, a satire, a whim, a nest of dreams, an invitation to wonder, and it leaves me on the threshold of yet another world—one which bears the promise of sounding the world of the Garage to its depth.

Perhaps no such sounding is possible. The secret of other worlds is that they are other worlds; from this world we often catch of them no more than fleeting, insubstantial glimpses. We may remember them, but not live in them, any more than we may live other lives than our own—except perhaps, briefly, in dreams. Or in the dreams made for us by others, out of their sensitivity and their suffering, as a substitute for an impossible communication.