36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

29: Are you dead, Samuel L. Mohad?

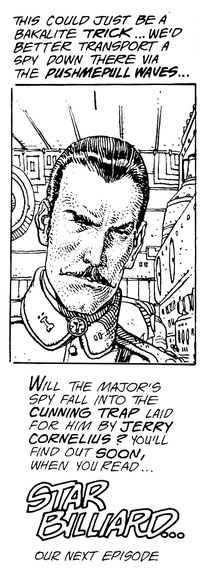

In 1977, when Major Grubert made his debut in English in the seventh issue of Heavy Metal, he was informed that his secret base had been invaded. He said,

“WE’D BETTER TRANSPORT A SPY DOWN THERE VIA THE PUSHMEPULL WAVES ...”

The original French was

“LE MiEUX EST D’ENVOYER UN ESPiON PAR ONDE PUCHEPULL...”

Now, “PUSHMEPULL” sounds quite silly in English, but at least it acknowledged Giraud’s translingual play on words. In the 1987 translation, all Grubert says is,

“THE BEST THING TO DO WOULD BE TO BEAM DOWN A SPY.”

That’s just avoiding the issue. Let me propose a translation that may improve on both of the above:

“BEST TO SEND A SPY BY POUSSETiRE WAVE...”

This involves a simple construction using two French verbs, “pousser” and “tirer”, which in English mean “to push” and “to pull”. Turnabout’s fair play.

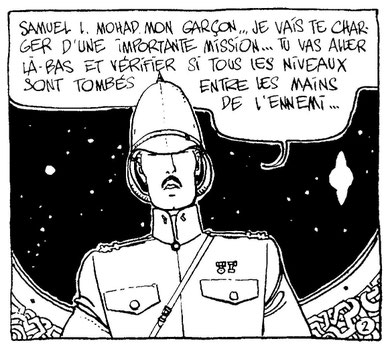

This translation is also closer to the original in another respect. When Grubert makes his proposal, he’s in his spaceship; but to argue that his intention is to “BEAM DOWN” someone (as they do in Star Trek) involves an assumption about what’s going on that is possibly a blunder. The 1987 translation repeats this in episode 4, where “TO BEAM DOWN THERE” stands in for “ALLER LÀ-BAS” (“TO GO DOWN THERE”)...

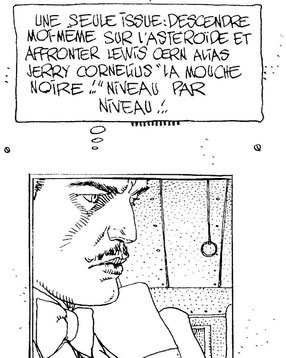

... and in episode 5, where the French is simply “DESCENDRE”.

So what’s the difference between a transporter beam and the poussetire wave?

Well, the main difference is that the poussetire wave may not be a transporter beam. Giraud’s play on “push/pull” might just as well imply some kind of mechanical operation, or else a two-way communication. We sometimes find “push” and “pull” on either side of a door, and doorways linking dissimilar spaces are a recurrent feature of the Garage. But a wave is indicated here—so what about a mechanical operation controlled by radio transmission through such a doorway? The mechanical operation, for instance, of a spy.

This speculation is consistent with what may be clearer if we shine a light on the original in two places where translation leaves the matter in obscurity. In 1979, Giraud revised the text in episode 18 in order to have Orne Batmagoo refer to “L’ ESPiON ELÉCTRONiQUE”, which might be translated simply as “THE ELECTRONiC SPY”. In the 1987 translation, this became “THE ANDROID SPY”. And in episode 21, the Major’s spy is identified as an “ANDROID DUPLICATE”, whereas the original is “DOUBLE MÉCANiQUE”—a mechanical double. The term “android” may tend to suggest a duplicate capable of independent action, whereas the term “mechanical” more obviously directs us to the possibility that the double is controlled, perhaps at every moment, by an operator aboard the Ciguri.

The latitude of the original text is further restricted and redirected when Grubert blandly says to Okania,

DON’T PANIC, HE WAS ONLY AN ANDROID DUPLICATE. THE REAL SAMUEL MOHAD IS STILL SAFELY ABOARD THE “CIGURI”.

The translation of the second sentence is accurate, with the exception of “SAFELY”—absent from the original, but typical of the emotional and informational flattening that plagues the 1987 translation. It’s responsive to Grubert’s “RASSUREZ VOUS”, which might have been translated as “SET YOUR MiND AT REST”. “DON’T PANIC” is a plausible translation, but its disadvantage is that Grubert is telling Okania not to do something rather than to do something. This subtly shifts attention to her (potential, not actual) reaction, while diverting us from Grubert’s action. He tells her not to panic, which implies, reassuringly, that she has no need to panic, because this is “ONLY” a duplicate, not the original Mohad—and then confirms that Mohad is safe.

If I read the French, however, as

CALM YOURSELF... THiS iS NOTHiNG BUT A MECHANiCAL DOUBLE... THE REAL SAMUEL MOHAD iS STiLL ABOARD THE CiGURi ...

it leaves me freer to observe that Grubert’s attention isn’t focused on Okania. He’s looking away from her; away, too, from the immediate drama to which everyone else is attending. He invites her to restrain her emotions, something in keeping, perhaps, with his own emotional restraint—he is allowed, perhaps, only one genuine smile in the whole of the serial—but also, more importantly, in accord with his evident intention to quit the scene of the crime with as little fuss and as quickly as possible.

And it leaves me free to wonder whether, while operating the mechanical double by means of the push-pull wave, Sam might conceivably have been traumatised, injured, or even killed by its destruction. One may hope not, or conclude that it’s unlikely; in any case, it’s a possibility hardly broached by the narrative, except when, in the last episode, Grubert reflects on Sam’s “MURDER”; but the Garage is impoverished where such possibilities as the text allows are eliminated by translation. What might we have suspected about the Major’s character if allowed to wonder whether his bland assurance (which does not go so far as to insist on Sam’s safety) was made in the knowledge of a fatal outcome?

Does he even care? Or do his own interests always take precedence?

Or is it all (as Barnier will ask in the next installment) just a game?

Or even a joke? After all, Sam’s story is brought to an end in an image that reframes and partly deflates the reader’s understanding of what has gone before. Yet it retains too much of mystery to produce the sudden relief of comprehension that results in laughter.

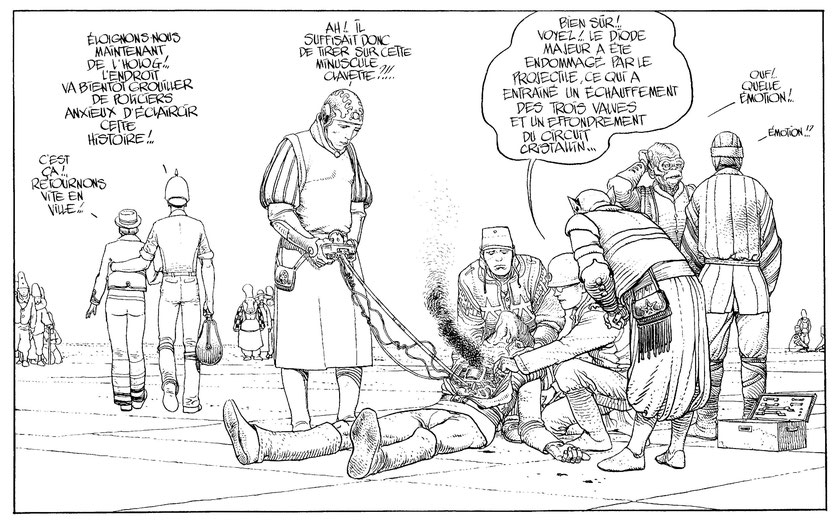

The grouping around the body is posed with an exquisite but lifeless precision that leads me to suspect a burlesque of that genre of painting devoted to the death of great men. Sam lies on the ground, his tunic opened—his chest opened—surrounded by attendants and witnesses. Murdered by an assassin, his condition is nevertheless explained as a mechanical malfunction.

Well, so shall it be for most of us: life, that rich tangle of impressions, relations, hopes and fears, extinguished in the end by a mechanical malfunction. The exchange between the two figures on the right echoes this dichotomy: “OOF! ” says one individual, “SUCH EMOTiON! ”—while the other responds, “EMOTiON!? ”.

Depends on your point of view, really.

Is murder now undone, reduced to comedy? Not necessarily. The act of murder and its revealed intention are not repealed. In Ray Bradbury’s “Punishment Without Crime”, a man is executed for murdering a “marionette”, even though the human original is unharmed. By the same token, Grubert’s later reflection on Sam’s “MURDER” need not be taken as definitive evidence that Sam—the real Sam—is dead. But meanwhile, the only Sam we know breathes no more.

And Grubert is already leading Okania away, telling her “THE PLACE WiLL SOON BE CRAWLiNG WiTH POLiCE ANXiOUS TO CLEAR UP THiS STORY!..”

I’m still on your trail, Grubert.