36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

34: What’s a poor puppet to do when offered a pair of scissors?

At first his dreams were chaotic. A little later they were dialectical...

(Jorge Luis Borges, “the Circular Ruins”)

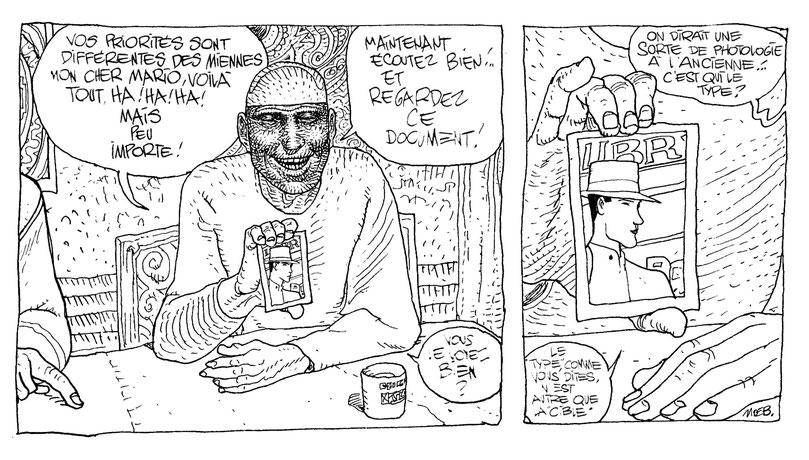

Grubert, in the last episode of the Garage, claims that autonomy for the world he created was intended from the outset. But in the sequel, L’Homme du Ciguri, Cervic puts the matter a little differently: he suggests that when the world of the asteroid turned against its creator, this was in accordance with Grubert’s own secret desire. Giraud here appears to recognize that Grubert’s earlier assertion was not to be trusted.

Though at first just one character in the gradually enlarging cast of the Garage, there are indications, as early as episode 4, that Giraud quickly decided Grubert was, in some way, creator of the world in which the story was set. This would be set out explicitly in episodes 15 and 16. By that time—and indeed, from the moment he reaches Armjourth in episode 10, not only wearing his helmet, but carrying his bag—Grubert has become the focal character, even if absent from the story for much of the time.

When Sper Gossi, in the last installment, announces that it’s time for the asteroid to choose its own destiny, Grubert is confronted by a reaction against his own original character in a story that might have turned out very differently if Giraud himself had not also been on a trajectory of self-transformation. It would be a mistake, however, to insist that, because Grubert’s character had by this stage subtly altered, he is necessarily sincere in asserting that “THE AUTONOMY OF THIS ASTEROID HAS ALWAYS BEEN PART OF ITS PROGRAMMING”. It may be true insofar as it echoes Giraud’s willingness to let the story take its own course, but, when Grubert makes that claim, he’s also trying to distract Gossi by angering him. If he’d said, “Look out, behind you!”, then jumped at Gossi as he looked round, would we be justified in believing there was really something behind Gossi?

In episode 15, the archer (who, despite our reliance on the information he imparts, may not fully grasp the situation) indicates both that Grubert is creator of the world in which the action of the story takes place, and that forces of resistance are seeking independence (on all three levels) from his influence. Since Gossi is identified (in 16) as an agent of the Tar’haï revival movement, the destruction of Grubert’s Star Billiard by the Tar’haï juggler (in 4) may be considered the first act of resistance recorded in the book. It’s less clear how co-ordinated or coherent subsequent actions are: both the pilot of the Airplane of Destiny (in 7) and the supposed ticket inspector (in 8) are later revealed to be under the authority of the President of the Second Level, but if their actions are directed against the Major’s spy—Star Billiard’s pilot—they are singularly ineffective, for both the spy and his companion are still at liberty when they later contact the Major (in 18).

The President appears fully involved in a fight against both Grubert and Cornelius, and episode 25 makes clear she has supposed the archer an ally. As for the archer, his part is hardly explained in the Garage; but when he makes his appearance in the Singing Caverns (11), he’s in the company of a Barcoll—Jasper—dispatched by Jerry Cornelius to find the missing engineer, Barnier. How much of what the archer subsequently tells Barnier was communicated to him by Jasper is unclear, and the archer was evidently not yet certain of Cornelius’s true intentions.

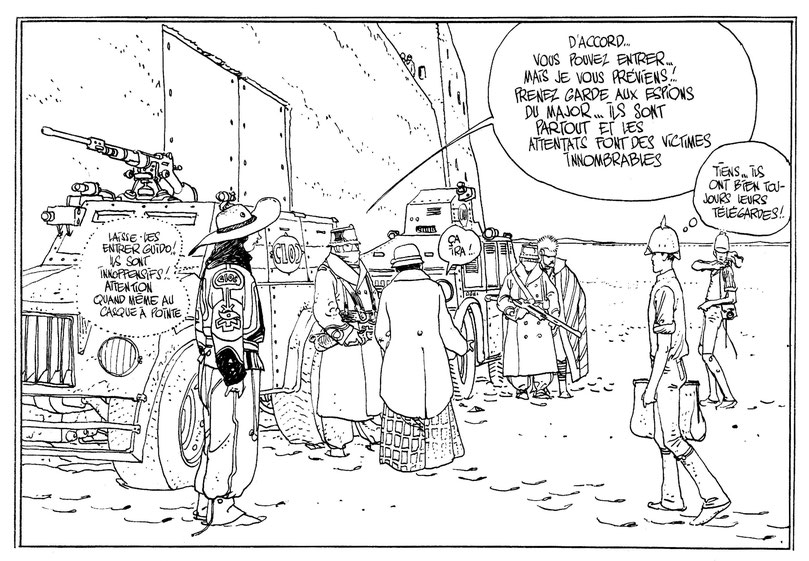

What’s missing from this account are one or two clues that originally signaled how tense and unstable the situation inside the asteroid was when the story was originally published. The murder of a guard in 3 and an apparently unprovoked bombing in 7 are still part of the story, as is the moment when Sper Gossi holds a gun to the Major’s head in 12, and entertains the prospect of killing him; but context and motivation are not altogether clear. It was clearer in episode 13, when it appeared in 1977; but in 1979 the fourth page was re-written in a way that changed the tenor of the action:

Sper Gossi leads Grubert to the large building seen on page 2, but the entrance is guarded. Gossi offers one of the guards a rather garbled account of the situation, and, in the first panel on page 4, the individual on the left says something in a whisper. The guard speaks to Sper Gossi, Gossi replies, and Grubert indulges in a thought balloon. The original and the revised versions are radically different:

1977

LET THEM ENTER, GUiDO!.. THEY’RE HARMLESS!.. BUT WATCH OUT FOR THE ONE iN THE POiNTED HELMET

OKAY... YOU MAY GO iN... BUT I’M WARNNG YOU! BEWARE OF THE MAJOR’S SPiES... THEY’RE EVERYWHERE, AND AMBUSHES ARE iNNUMERABLE

WE’LL MANAGE!..

WELL... THEY ALWAYS HAVE THEiR TELEGUARDS!..

1979

WHAT AN ECCENTRIC OL’ SPER IS ...

OKAY, YOU CAN GO INTO THE HOLOG ... BUT BE CAREFUL! ACCESS TO THE YARD WHERE THEY’RE KEEPING THE SPLENDID LOCOMOTIVE IS SEVERELY RESTRICTED! I’M SAYING THIS FOR YOUR FRIEND, OF COURSE!

NO PROBLEM!

THE TRAIN...? POOR SAM ...

As usual, my translation of the original French (1977) is a little shaky, but the revised version (1979) is fairly represented by the Lofficier translation, quoted above.

It’s plain the 1979 version takes its lead from what happens in the following episode, while downplaying the extent of political instability and paranoia in the world of the asteroid. Sper Gossi is not recognized in the original, nor is there any mention of the holog, the steam train or Samuel L. Mohad; but all the revision adds, where it is not redundant, is a non sequitur (why is Gossi referred to with such familiarity?) and an inconsistency (restrictions on the yard where the locomotive’s being repaired seem, in the next episode, not too severe). What’s lost, on the other hand, is the fact that Grubert (not Gossi) is a figure familiar in this world, as the subject of rumor (a point that will be picked up and elaborated on in episodes 15 and 16) and a focus for anxiety.

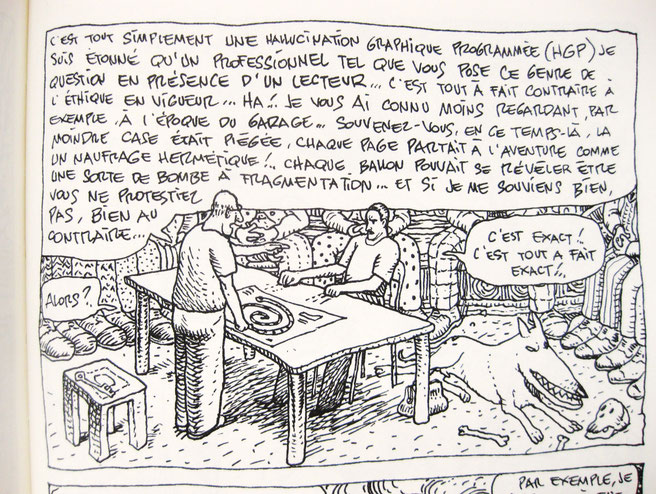

Grubert, within the fiction, is creator of a world. Outside the fiction, Mœbius—Giraud’s alter ego—was also creator of that world. Grubert may have been, in the beginning, the butt of Giraud’s jokes, but his role in the Garage came to parallel that of his author: both were responsible for the world of the story, and both were uncertain what would happen next.

In the sequel, L’Homme du Ciguri, more than a decade later, Giraud teased Gruber (as he was henceforth called in French) with the possibility of knowing he’s not a creator but a creation: Gruber reads the story of his earlier adventures in a book; he seeks out its author; and, while speaking of his own creative endeavors, his own creator sits silently with his back turned, drawing. It wasn’t yet time for Gruber to learn who and what he was.

A few years later, in a small town on the outskirts of Armjourth, Gruber finds political ferment still bubbling, and gets himself hired as an assassin by a radical group determined to put an end to his interference in their world. Having only a picture of the Major as he appeared in L’Homme du Ciguri—no helmet, no mustache—these revolutionaries fail to recognize their adversary. But perhaps, after all, they are opposed as much to a principle as to a person.

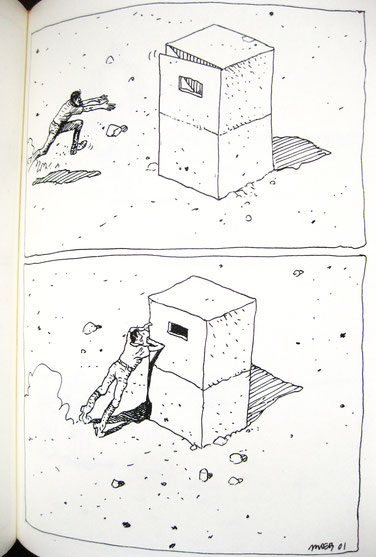

When this story (which later became Le Chasseur Déprime) was set aside, Gruber sought refuge in a box in a desert he considered his own. And why not? Numerous details suggest this desert occupies a space in the expanded, multi-level asteroid of the Garage. But Gruber’s freedom of action had been curtailed, and Giraud was sending characters to torment him with supposedly profound but rather dry questions, like, “What is good?” Gruber (who showed no sign of being particularly adept, nor very comfortable in answering such questions) was of course unaware that his “adventures” were now taking place entirely in Giraud’s private notebooks, rather than in the pages of a magazine.

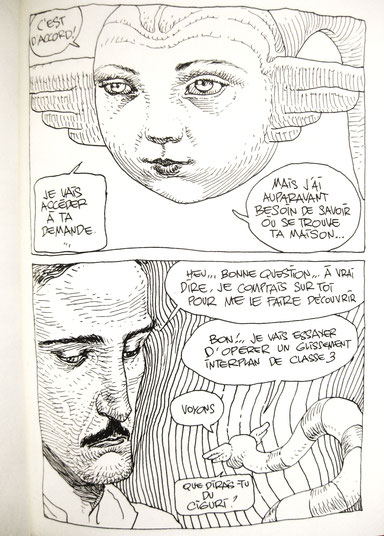

Le Major was finally published in 2011, the year before Giraud’s death. The first three chapters had been drawn ten years earlier. Readers familiar with the Mœbiusphere would hardly have been disturbed by the discovery, in the third chapter, that the interior space of Gruber’s oracular cabin is actually larger than it appears from the outside. Night has fallen, we’re told, on Desert “B”. No one else is coming to ask questions, and the Major has an itch to consult the spiral spirit—Tar’haï magic, a further confirmation that Desert “B” is located in the world of Gruber’s adventures, a world of his own making.

His invocation begins with the familiar words, “STOE ORKEO”. A tiny manifestation of the spirit appears with a plop. Gruber has a hankering to go home, but doesn’t know the way. The best the spirit can offer is a return to the Ciguri. Not good enough—but in an effort to be obliging, the spirit attempts to open a class 3 interplane slide.

Things are not going well today for Gruber: the planeslide doesn’t come off, and he ends up performing a brief reprise of Mœbius’s “Absoluten Calfeutrail” (Metal Hurlant #16)—in other words, falling at great speed toward the desert, and landing with a KABOOOUM. (Mœbius himself would repeat this pratfall several times in the course of Inside Mœbius.)

Meanwhile, two characters—Whatson and Senateur—go on with their parched metaphysical quibbling. Seeing the Major fall from the sky, they seize the opportunity to ask him one or two questions.

Gruber’s in no mood to answer, and calls out, “HEY!.. YOU TWO ... GET AWAY FROM HERE! I’LL POiNT OUT TO YOU THAT YOU’RE iN MY DESERT ! ”

Senateur and Whatson hold a different, and rather alarming opinion. “WHAT’S HE ON ABOUT NOW ?” says Senateur to Whatson. “HiS DESERT !!!”

“YOU’RE RiGHT!..” says Whatson. “THiS iSN’T HiS DESERT AT ALL!!!! ” And, to Gruber: “YOU’RE REALLY MAJOR GRUBER, AREN’T YOU ?.. THE MAN WiTH THE FiNE MOUSTACHE ! ?? ”

“CORRECT,” says Gruber, “AND I iNViTE YOU TO LEAVE THiS DESERT iMMEDiATELY! ”

“THiS DESERT DOESN’T BELONG TO YOU!” replies Whatson. Then he and Senateur tell Gruber, with considerable emphasis, that, “THiS DESERT BELONGS TO THE AUTHOR!..”

“TO MŒBiUS!..” adds Whatson.

“TO MŒBiUS ?” says Gruber. “BUT... iT’S IMPOSSiBLE!.. MŒBiUS iS NOTHiNG BUT A MYTH!.. A RiDiCULOUS BELiEF THAT SURViVES ONLY THROUGH THE CREDULiTY OF THE iGNORANT MASSES ... iF HE EXiSTED, iT WOULD BE COMPARABLE TO THE iDEA WE HAVE OF... OF... GOD ... HAVE YOU TAKEN ACCOUNT OF THE CONSEQUENCES? HE WOULD BE, iN EFFECT, THE AUTHOR OF ALL OUR EXiSTENCES... HE WOULD BE ALL-POWERFUL!.. OMNiPRESENT, EVEN TO THE DEPTHS OF OUR SOULS ...”

Grubert himself, in the Garage, was considered by some a semi-mythical being, a demi-god. Here the tables are turned and, at last, he has to face the fact that not only he, but the entire world in which he acts, is the creation of another demi-god. That he recognizes the name Mœbius may reflect the potential that, as a comic book character and an expression of the will of his creator, he might have been obliged at any time to express an awareness of his role. In episode 9 of the Garage, for instance, when Grubert seems to refer to the title of the strip in which he appears, he may be addressing the semi-aquatic animal on whose back he’s riding, but he’s just as surely addressing the reader. Giraud’s subtlety in deploying this essentially comedic and disruptive device is consistent, however, with his later disinclination, in L’Homme du Ciguri, to turn and face Gruber.

In the notebooks, however, time has moved on. It’s 2001. Giraud has not only adopted the desert occupied by Gruber as a realm for self-exploration; he has begun drawing the chronicle Inside Mœbius, in which Gruber will share scenes both with his creator and with the author’s other characters. The notebook episodes forming Le Major serve as a kind of bridge.

The stages of Mœbius’s own occupation of Desert “B” are slightly mysterious, but the essential points are clear: Giraud’s encounter with the Mexican desert on the brink of adulthood was a profoundly enriching experience that continued to nourish him throughout his life. The internalised experience could be re-externalised as a setting, a stage, or an opening onto the creative impulse. Desert “B” appears to be a self-conscious foregrounding of this process, but I don’t know exactly when Giraud first gave it this name. The foreword to the Dark Horse edition of Inside Mœbius lets us know the series “unexpectedly emerg[ed] from the universe designed for 40 [days] dans le désert B”. The drawings for that book were executed in 1999 and published the following year. According to Isabelle Giraud, the artist’s

resolve to stop smoking weed—and thus to “weed himself out”—provided the landscape for this Desert B, at the heart of which he established a setting for psychic expression.

(Inside Mœbius part 1, p.6)

The translator’s notes (Inside part 1, p.222) explain that “to weed” is in French “désherber”, and that “the pronunciation of désherber is identical, in French, to that of Desert B.”

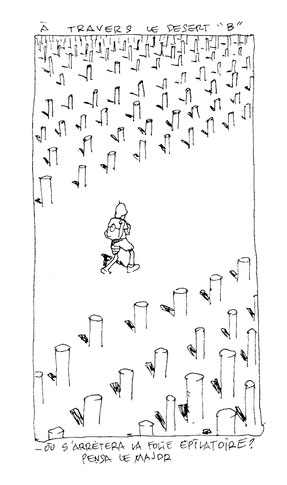

One might get the the impression from this that Desert “B” got its name in 1999; but the little book, Folles Pespectives, from 1996, already has three drawings from Giraud’s notebooks that are identified as featuring Desert “B”. In one, the Major—who else?—is attempting a crossing:

Even so, Mœbius’s assertion of ownership of the desert can be dated to 2001. Early in the first part of Inside Mœbius he enters a mysterious temple where a blindfolded naked woman tries to tempt him by presenting him with his old wooden pipe, packed with weed. It’s a trap, he realises, but she asks, “WHAT ARE YOU AFRAiD OF? YOU’RE HERE--iN YOUR OWN DESERT! YOU’RE AT HOME.” On the next page he realises that, “ALL THE SAME... ... iT’S TRUE. THiS DESERT IS MiNE. ” On the following page he begins to draw the strip with a pen, rather than a brush—a sign that this is now a “Mœbius” strip—and immediately stages a confrontation with his younger self, a figure representing the person he was when his work as Mœbius produced both a radical transformation of his career, and of his creative effort.

The adumbration of his ownership continues throughout the series:

Within twenty pages, the figure who represents the author is telling himself (and the reader) that “THiS iS MY DESERT! MY DESERT “B”!” In part ii, “DESERT “B” iS MiNE”, and it’s “MY DESERT”. Later he says, “I’M AT HOME HERE iN MY COMiC! MY DESERT “B”... I’M THE MASTER COMMANDER HERE! I’M GOD!”, by which he means that “[T]HE ARTiST iS FREE TO WEAVE HiS WORLD AS HE SEES FiT”. He subsequently explains to Osama Bin Laden (an unwilling and not altogether welcome guest) that “EVERYTHiNG YOU SAY AND DO iS UNDER THE AUTHOR’S ABSOLUTE CONTROL”; and in part iii he returns to the argument that because he’s “CREATOR” of this desert, he’s “A KiND OF GOD HERE”. In part vi, he says, “I CREATED DESERT “B” JUST FOR MYSELF”, and tells Gruber that, “EVERYTHiNG HERE BELONGS TO ME, EVEN YOU!”

Much of this represents an essentially accurate statement of the relation between the artist and his work: Giraud was responsible for it, and it was subject to his whims. But what he says is also undercut by irony: the figure used to represent the author is essentially comic, and, in his assertions of godhood, Giraud makes him ridiculous.

As ridiculous as Grubert once was.

And it’s the parallel between Grubert in 1979 and Mœbius thirty years later that finally convicts Grubert of insincerity in the assertion that his creation was designed to attain its autonomy. Not for nothing does Grubert dress in a uniform that betokens colonial enterprise. It’s never in the colonialist’s interest to relinquish power. And Mœbius’s assertion of his own power illustrates this.

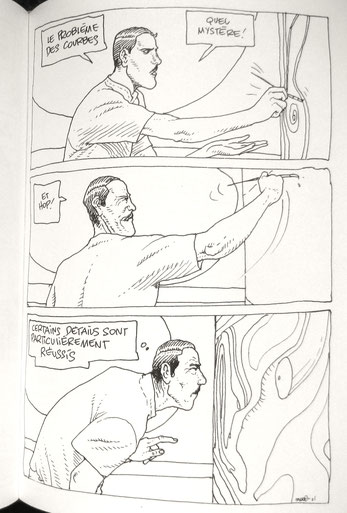

When Giraud had completed the bulk of Inside Mœbius, he returned to the notebook chapters featuring the Major, picking up where he left off. Already, in 2001, he’d driven home the point—that this was not the Major’s world—with a gag. The Major was decorating his bunker (it still looks like a crate from the outside) by painting some of its corridors, just as Osborn Fildegar painted the endless corridors of his spaceship in 1979’s Tueur de Monde. And among the details the Major has painted, he spots, as if surprised, a detail: one tiny figure in the midst of a crowd, who turns out, on closer inspection, to be the same caricature of a younger Mœbius that plays a part in Inside Mœbius—the same Mœbius who placed a tiny self-portrait in the midst of the two-page battle scene in “Harzakc”, to which this is a reference.

In 2006, he followed this up with another gag. Gruber heads for corridor 22 until he arrives at the holy of holies, his heart thumping in his chest because what he’s about to do is doubly taboo. He’s about to look upon something he may not look upon without being forever changed. He hesitates, perhaps understandably—but at least one, and possibly both pages of hesitation were interpolated in 2007. In these, Gruber is a man conflicted, a self-declared rationalist out of touch with his dreams, who knows he’s “ALONE, FAR FROM HOME, LOST, ASTRAY!..” And why? “TO SATiSFY A GOD ALL-POWERFUL BUT STUPiD, ASLEEP iN HiS PONDEROUS COFFiN...”

To which all-powerful god is he referring? I’m sure you don’t need me to tell you he’s referring to his author, his creator, the creator of the world in which he exists—Mœbius. But what Gruber says to himself sounds an echo of those murky alliances, the forces of resistance alluded to by the archer in episode 15 of the Garage. “I MUST REACT!..” says Gruber, “I MUST FREE MYSELF”. Indeed, it’s why he’s come to corridor 22, and is prising open its mysterious sarcophagus. He’s here to confirm something that concerns his “DESTiNY AS MASTER OF THE HERMETiC GARAGE”.

The story—it is by this point becoming a story—has yet some turns to take, but one of its later pages has already been drawn, on which Gruber asks himself, “MY DESiRE FOR LiBERTY, iS iT JUST A LiE!? ”

His desire for liberty. As a created character in a created world.

The marvelous, enigmatic pages that bring the strange and elastic saga of the Major to its end are mostly dated 2007 and 2008, but its last words were added in 2009, when Mœbius and Gruber sit down together for a brief but significant exchange. On the subject of the instability of desert “B”, Gruber ventures that, “FAR FROM BEiNG THE SiGN OF A GREAT FREEDOM ... [it] ... iS iN FACT THE CLEAR SYMPTOM OF A DiSORDER OF THE SPiRiT, OF A GRAVE EMOTiONAL DEFiCiENCY WiTH RESPECT TO YOUR OWN CREATiON...” (p.269)

Mœbius agrees, but doesn’t appear to take the matter seriously, which irritates the Major.

“iT’S OUT OF THE QUESTiON THAT ALL THiS CAN REMAiN WiTHOUT AN ANSWER! ” says Gruber (p.271); but Mœbius considers the situation absurd, and explains:

YOU’RE NOTHiNG BUT A CREATiON !.. iT’S ME WHO HAS iNVESTED iN YOU A CERTAiN LiBERTY, AND I’VE ENSURED THAT MY POWER SHOULD ALWAYS BE JUST AND LAWFUL ... I ALWAYS PLACE MYSELF iN QUESTiON ... BECAUSE, YOU SEE, iT’S ACCEPTED THAT POWER CORRUPTS, LiKE THE POWER OF AN ARTiST OVER HiS OWN CREATiON ... FROM WHENCE COMES YOUR OBSESSiON WiTH ABSOLUTE “FREEDOM”.

(Le Major, p.271)

Did Grubert once place himself in question as Giraud has done? And was that question any the less underwritten, undermined and answered by the totality of his power over his creation?