36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

4: In which two bodies are briefly unearthed

This wasn’t the world Jerry had always known... but he could only vaguely remember a different one, so similar to this that it was immaterial which was which. The dates checked roughly... and the mood was much the same.

(Michael Moorcock, The Final Programme p.63)

At some point, probably in late 1975 or early 1976, Jean-Pierre Dionnet, editor of Metal Hurlant, found Giraud’s two-page gag about the ruined cableur and asked him to draw a continuation. Later,

[Dionnet] called to pester me about the next installment. There was panic. I had to work like a madman for two days, but not having kept photocopies of the first two pages, I drew two more, the coherence of which was not guaranteed.

(introduction to Le Garage, 1995)

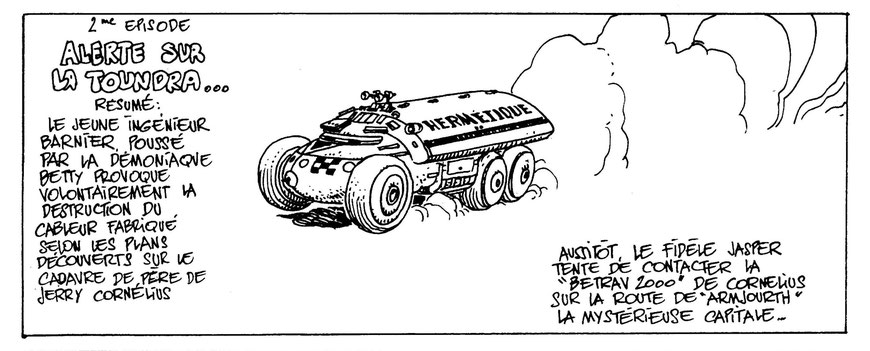

Most of the second episode consists of invention; but it’s invention that rests, however lightly, on the bare bones of what went before. The individual responsible for the mishap with the cableur is immediately given a name—“YOUNG ENGiNEER BARNiER”—though he’s pictured pulling on a fur coat and wearing boots that hide the costume he wore in the first episode. The ruined cableur is not seen.

Nor is the character to whom the name of Jerry Cornelius is meanwhile attached: driving across “THE TUNDRA” in a large tanker, he’s heading for Armjourth, “THE MYSTERiOUS CAPiTAL”—mysterious presumably because it’s the capital of who knows what? Presumably Giraud didn’t know. Cornelius is contacted by another character, again not pictured—the faithful Jasper—and the reader is allowed to eavesdrop on the conversation of these two unseen characters.

Giraud also used the recap at the beginning—the “RÉSUMÉ”—for the first time (if not the last) to invent background for the story. My own tentative, fairly literal translation indicates that

YOUNG ENGiNEER BARNiER, GOADED BY THE DEMONiAC BETTY, HAS WiLFULLY CAUSED THE DESTRUCTiON OF THE CABLEUR MADE TO SPECiFiCATiONS FOUND ON THE CORPSE OF JERRY CORNELiUS’S FATHER.

(Metal Hurlant #7, April 1976)

When it appeared in Heavy Metal, a year and a half later, this was rendered as

THE YOUNG ENGINEER, BARNABUS, UNDER THE SPELL OF THE EVIL BETTY, DELIBERATELY CAUSED THE DESTRUCTION OF THE TRANSPORTER WHICH HAD BEEN MADE ACCORDING TO THE PLANS FOUND ON THE BODY OF JERRY CORNELIUS’S FATHER.

(Heavy Metal #7, October 1977)

I suppose it was almost inevitable, when the serial was later collected as a book, that this would be changed. I’m free to wonder whether, back in 1976, Barnier might have caused the destruction of the cableur “deliberately” or “wilfully” or (closer to Giraud’s working method) “spontaneously” or “freely”—all potential translations of “VOLONTAiREMENT”—but the simple fact is that “LA DEMONiAQUE BETTY” was in evidence neither in the first episode, nor (by the time the serial concluded) in any other. Jerry Cornelius, Jasper, their respective vehicles, Armjourth, and the Singing Caverns mentioned by Cornelius would all play a part—but not Betty. Cornelius’s father was likewise not merely dead, but a dead end. Both were eliminated from the text when the book MAJOR FATAL was published in 1979.

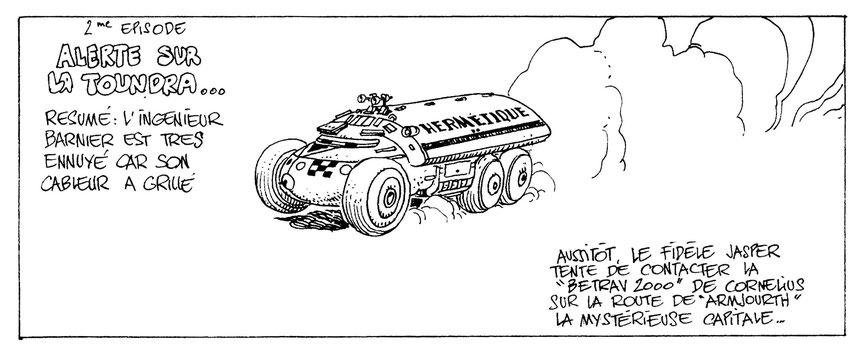

Revision changed the tone of the second episode. The element of culpability initially attached to Barnier—along with the suggestion of multiple and mysterious pressures acting upon him—is unavoidably lost (along with Betty and Papa Cornelius) when the revised RÉSUMÉ reports that

ENGiNEER BARNiER iS VERY WORRiED BECAUSE HiS CABLEUR GOT FRiED

Again my own crude representation of the French. The cableur was “GRILLÉ”—literally “grilled”, but indicating something like the blowing or burning out of an electric component. (I decline to propose that Barnier was worried “because his cableur was toast”—too flippant, and, to my ears, anachronistic.) The 1987 translation was

ENGINEER BARNIER IS VERY UPSET BECAUSE HIS CABLEBOX EXPLODED ...

Fair enough.

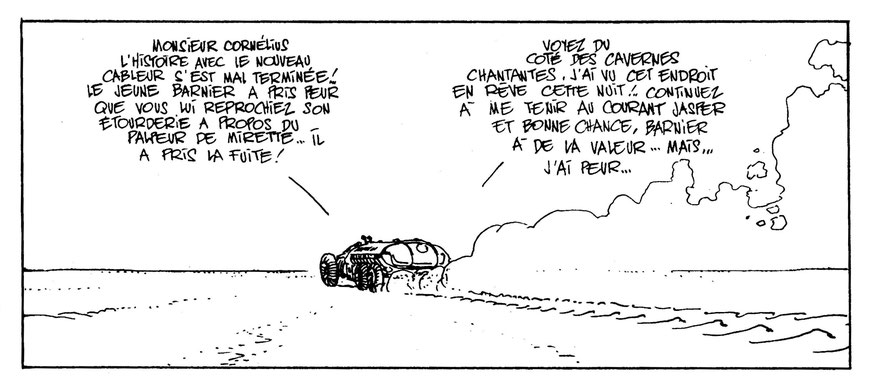

But, reading the text in all its versions—and reading around it—I notice that the elements of culpability and wilfulness now absent from the “RÉSUMÉ” remain consistent with Jasper’s characterization, later in the episode, of what happened to the cableur. He refers to Barnier’s “ÉTOURDERiE”. Translated as “THOUGHTLESSNESS” in 1977, this became, in 1987, “BLUNDER”.

Perhaps Barnier was simply absent-minded or clumsy; but those familiar with the Garage will doubtless recall that Barnier is also capable of criminal recklessness—as manifested dramatically in the third episode. If his action there seems unfounded, possibly it’s because its foundation here has been largely effaced. Giraud, describing the origins of Major Grubert, referred to the Ramenez-les Vivants (Bring ‘Em Back Alive) comic strip, with its “tense, nearly paranoid atmosphere”, and it’s worth being alert to the fact that (once the opening gag had been thrown way) the Garage began in the same key.

If this isn’t altogether obvious in the 1987 translation, it’s because that atmosphere has been attenuated. There, Cornelius ends his exchange with Jasper by saying, “BARNIER’S A GOOD KID...”

Jasper’s response is, “WE’RE ALL VERY CONCERNED, SIR...”

It sounds paternal, and cosy, as if Barnier’s part of a family, the head of which is concerned for his welfare. But the French of 1976 was open to other readings:

[Cornelius:] ... BARNiER À DE LA VALEUR ... MAiS ... J’Ai PEUR ...

[Jasper:] NOUS AVONS TOUS PEUR MONSiEUR ...

A fairly literal translation:

[Cornelius:] ... BARNiER iS VALUABLE ... BUT ... I’M AFRAiD ...

[Jasper:] WE’RE ALL AFRAiD, SiR ...

Now, it might be the case that Cornelius is saying Barnier is “TALENTED”, or is referring to his personal merit; but the 1987 translation opts for the latter reading so decisively that other possibilities are more or less excluded.

How was Cornelius’s estimate of Barnier’s value originally qualified by the “fear” that he expressed? And what did he fear? That Barnier was now more a liability than an asset? That (as Jasper’s response appears to acknowledge) Barnier’s carelessness had endangered some larger scheme? Both speculations are plausible.

At this stage of the story, what do I, as an innocent and baffled (if curious) reader, know of the parties to this exchange? I’m not constrained to read what they say as an expression of concern for Barnier—and moreover, if I don’t, neither Barnier’s concern for his own skin nor his decision to make a run for it seem so exaggerated and unreasonable. Let me join up the three dots with a little imagination:

[Cornelius:] ... BARNiER iS VALUABLE ... BUT ... I’M AFRAiD [we may

have to get rid of him...]

[Jasper:] WE’RE ALL AFRAiD, SiR, [that his actions may have dropped us

in the shit... ]

Responsibility for loss of an undercurrent that motivates Barnier’s panic and subsequent flight doesn’t rest entirely with the translators. In 1979’s MAJOR FATAL, Cornelius’s confession of fear—“MAiS ... J’Ai PEUR”—was eliminated. It may seem a minor matter, but the excision of these three words also disrupts the connected flow of dialogue. Where, originally, the somewhat ominous note in Cornelius’s words was picked up and echoed by Jasper, it’s now Jasper who introduces it—“NOUS AVONS TOUS PEUR”—and this implies a very different set of possibilities. If Jasper is afraid, where Cornelius is not, is it simply because Jasper is more cautious or fretful?

And of what is Jasper afraid? Later in the story, Jasper will render assistance to Barnier; later still, it will become apparent Barnier’s life is in danger from another quarter. The translation by Randy and Jean-Marc Lofficier is in the second episode consistent with these points, and consistency was one of their stated aims. As a sympathetic reader of the Garage, however, I’m no longer persuaded it was the right moment to signal this, tonally, to the reader.

Feel free to object that I ought to accept the authority of the revision, and content myself with what may be accounted the authorized translation, but I decline to do so. If it seems I’m picking a needless argument over a trivial detail, nevertheless I hold several larger points in view:

(1) The Lofficier translation is serviceable for the most part, and has its happy moments, yet there are occasions when the offhand playfulness of Giraud’s text is blunted by what looks like insensitivity or overemphasis, or its irony is neglected, or its ocasional harshness is softened, or its ambivalences are tidied away by what constitutes not just a translation but a reduction.

I’ve no personal stake in this. With three versions of the story in front of me, I’m at liberty to make my own judgment. But, three decades and more since Marvel’s publication of The Airtight Garage, and with a new edition in English long overdue, is it too much to hope for a new or revised translation that might refine or clarify occasional lapses?

(2) In a comic strip, the authority of the word is not always, of necessity, paramount—though it can be difficult to read past the words where word and image are at odds. The Garage, however, does not represent the illustration of a pre-existing script; it is as much a sequence and ordering of images, scenes, expressions and gestures, as it is a text. The subsequent revision of a few words is, on close consideration, insufficient to conjure away the prior integrity—or, on some occasions, the complete absence of integrity—of its original creative thrust.

The Garage was a performance of a very particular kind, which survives on its pages with most of its whims and uncertainties naked to the eye; and that visible performance shaped my experience as a reader, with the support of the text. I’m curious to discover to what extent that experience has been altered by a few concessions (some necessary, some ill-judged) to a plot that can hardly be said to have existed when the edifice was erected.

(3) Also, to my astonishment, in reading the Garage—and its sequels—four decades after I first encountered it, and nearly three decades after I last looked at it, I find it alive.

I intend to bring it back alive.