36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

7: Who or what is a Mœbius?

What happens when I work as Moebius? Nothing happens, exactly. If someone else wanted to work as Moebius, they’d need to watch what I’m doing to do the same. For me to work as Moebius, I don’t watch anything. I do what I want, I sign it, and that becomes Moebius.

(Jean Giraud, Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.16)

Before I go further, I probably ought to clarify something. In these pages, I mainly refer to Giraud, or Jean Giraud, but sometimes to Mœbius, and occasionally also “Mœbius”. These variations are not entirely arbitrary, but may be potentially confusing, so I’ll try to make clear the principles underlying these choices.

Jean Giraud was born on May 8, 1938, and spent the early part of his life in Fontenay-sous-Bois, not far from Paris. He wanted to draw comic strips—bandes dessinées—and when he was seventeen, made his first sale. There’s little in his early work to suggest he was either precociously or prodigiously talented, but what he did have—and what he retained throughout his life—was a near-obsessive passion for drawing, and a willingness, which he pursued with great dedication, not only to perfect his craft, but to extend his range.

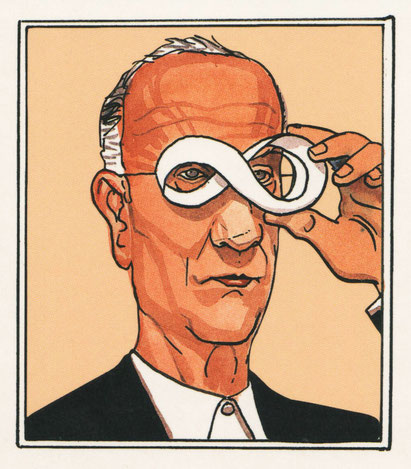

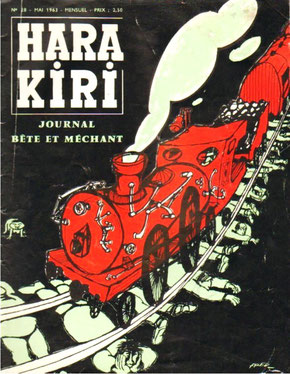

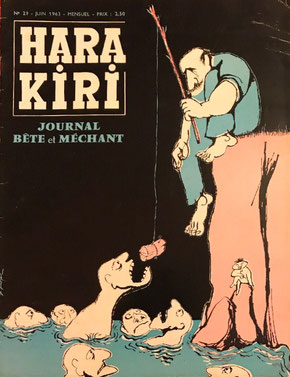

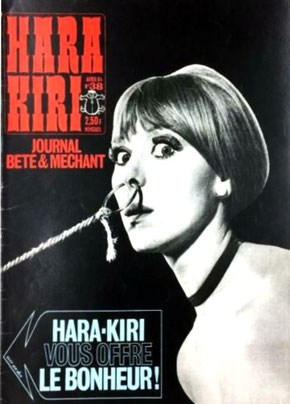

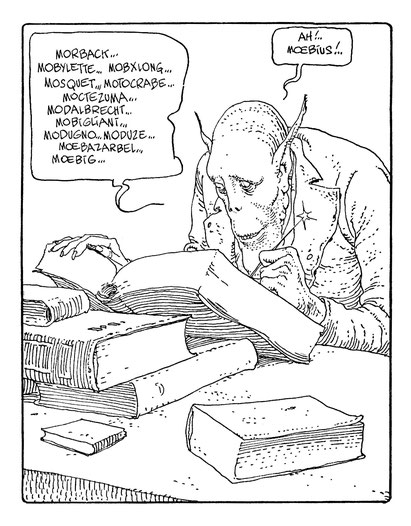

It was in 1963 that he first adopted the pseudonym “Mœbius” for short contributions to Hara Kiri—a satirical magazine whose subtitle identified it as “a mean and nasty journal”.

Giraud was something of a chameleon, and in these strips he showed off his familiarity with the artists working for MAD. He’d discovered MAD when it was still a comic book, back in 1955, on his first trip to Mexico: “It was at the front of all the bookstores... For the first time, I saw the work of Harvey Kurtzman and mostly Bill Elder: the pinnacle of American comic strips, the absolute genius” (histoire, p.163).

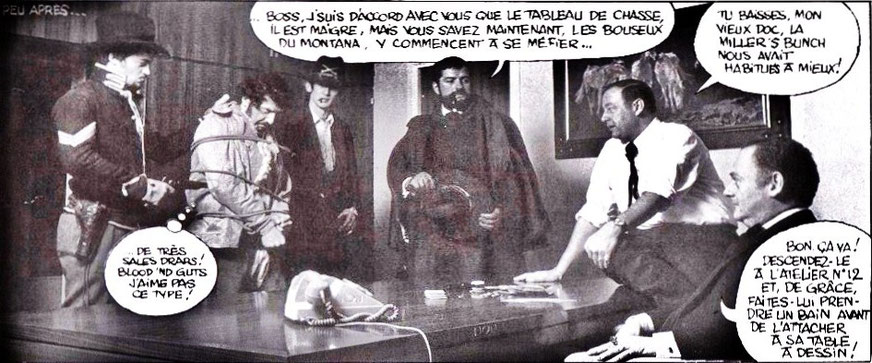

This sideline, as “Mœbius”, effectively ended as Giraud’s workload on a western series, Fort Navajo, increased. The series, which later became known as Blueberry, began at the end of October, 1963, and was immediately successful. Appearing in Pilote, and written by Jean-Michel Charlier, co-editor of the magazine, it demanded two pages, weekly, from Giraud. It ran almost continuously, with only a few weeks between one album’s worth of material and the next, for the first three years. When he signed the strip, he often used a contraction of his name, “Gir”. By 1970, he’d drawn eleven Blueberry albums, and was starting work on a twelfth.

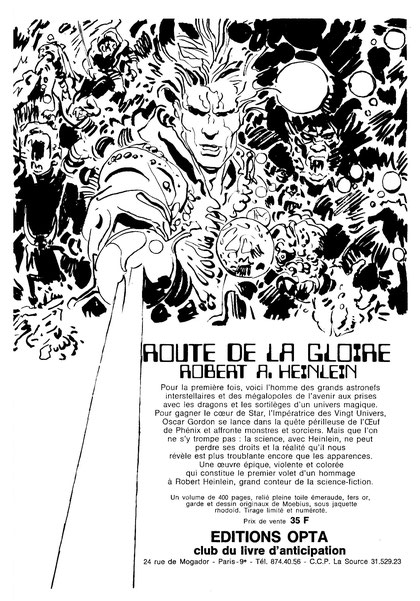

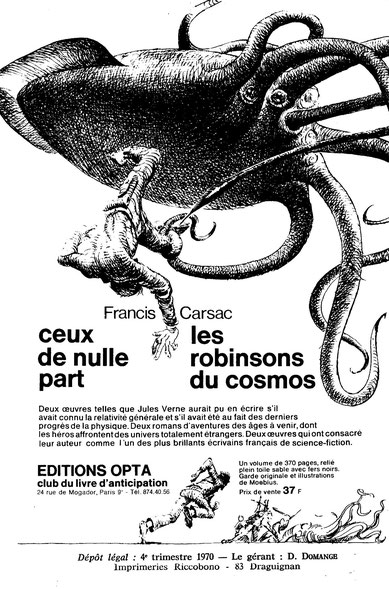

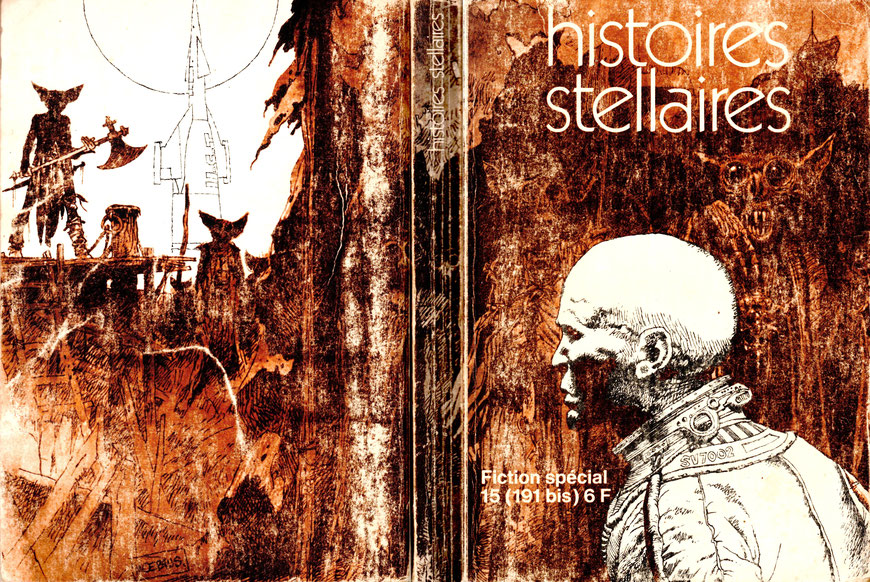

Up to that point, the longest break between Blueberrys had been in the first five months of 1969. It was around this time that the pseudonym “Mœbius” was picked up again in a different context, when Giraud started producing science-fiction illustrations for the publisher, Opta. These appeared in the magazine Galaxie (the French edition of Galaxy)...

... and in limited edition books published for Opta’s “club du livre d’anticipation”.

He also began producing covers for paperbacks.

I tend to refer to Giraud or Jean Giraud as a means of identifying, historically and biographically, the individual responsible for the artwork and stories about which I’m writing. Forty years ago, I’d have used the name “Mœbius” simply because it was the name I saw attached to the art, and knew little about the individual behind it. I wasn’t particularly curious.

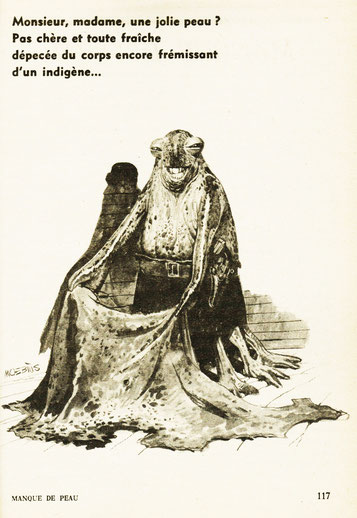

When I put “Mœbius” in quote marks, I’m usually indicating its status as an adopted name or its use as a signature. The first “Mœbius”, therefore, is the name Giraud signed as writer/artist of short satirical comic strips in 1963 and 1964; the second “Mœbius” was how he signed his science-fiction illustrations from 1969 on. In neither case need the name be regarded as anything more than a pseudonym, marking a body of work distinct and separate from the regular work for which he was better known. He said as much in 1989: “I decided to reuse the name... to indicate a clear separation in my work between that [the sf illustrations], and Gir’s.”

The “Mœbius” of the period 1974 through 1979, however, is something altogether more complex. During these years, Giraud produced the core work that invested the name with a creative life of its own.

Continuities may be detected. Most obviously, the illustrator of science-fiction known as “Mœbius” was still producing book covers and illustrations when the ten-page “L’Homme, Est-il Bon?” appeared in Pilote #744 (February 7, 1974), signed “Mœbius”. That story, however, was credited to “Giraud” on the contents page, and Giraud had already contributed several short science-fiction stories to the magazine:

“L’artefact” (Pilote Annuel, November 18, 1971);

“Barbe-rouge et le cerveau pirate” (Pilote Annuel, November 16, 1972);

“Il y a un prince charmant sur Phenixon” (Pilote #730, November 1, 1973).

When Commandant Grubert made his first (and, in retrospect, unrecognizable) appearance in “Les Merveilles de l’Univers” (Pilote #749, March 14, 1974), the strip was signed “Gir” and credited to “Giraud”.

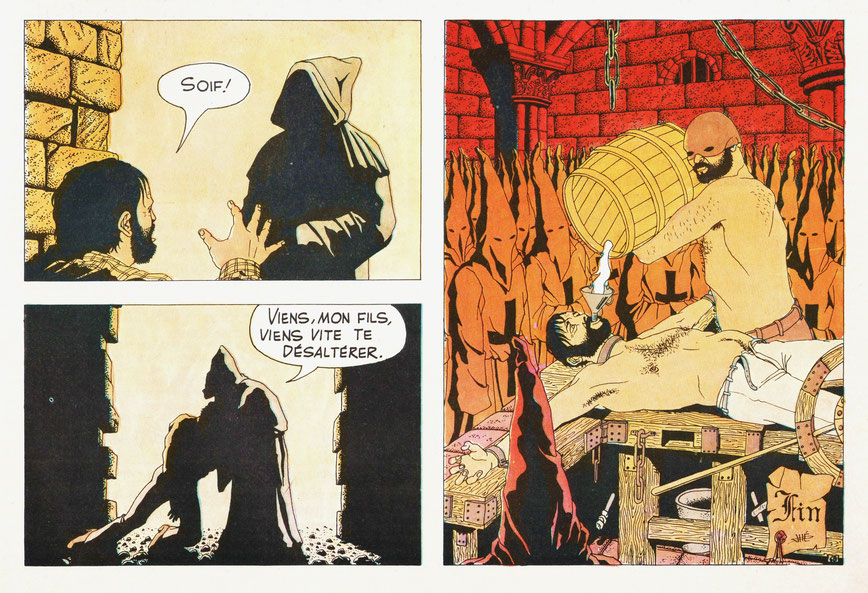

Another three strips in Pilote, drawn by newcomer Dominique Hé, for which Giraud was credited as co-writer, suggest that, as the third “Mœbius” was emerging, Giraud’s taste for sardonic humor, given free rein by the first “Mœbius”, remained undiminished. These stories were:

“Robinsonade” (Pilote #715, July 19, 1973);

“Jusqu’à plus soif” (Pilote #725, September 27, 1973);

“Pas de folie sans fous” (Pilote #751, March 28, 1974).

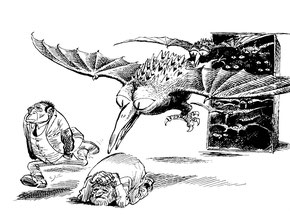

“L’homme, Est-il Bon?” was itself a rather unsettling joke, and—whimsical or dark, surrealist and transgressive by turns—humor animated the work of Mœbius over the next half-dozen years. The first album to bear the name “Mœbius”, Le Bandard Fou (1974), was a freewheeling piece of science-fiction, full of off-kilter gags, about a man with a persistent out-of-season erection. And when Arzach made its debut in the first issue of Metal Hurlant, the spectacular impact of the art may have partly disguised the fact that the artist’s sense of the absurd was still firmly in the saddle.

Continuities notwithstanding, the flowering of Mœbius—the essential, indelible Mœbius Giraud would live with for the rest of his life—was also during this period a very personal bid for creative freedom. As Mœbius, Giraud would illustrate a few scripts written by others, but mostly the stories were his own, and many were generated in an idiosyncratic manner. Rather than working from a full script, he would often improvise freely and playfully.

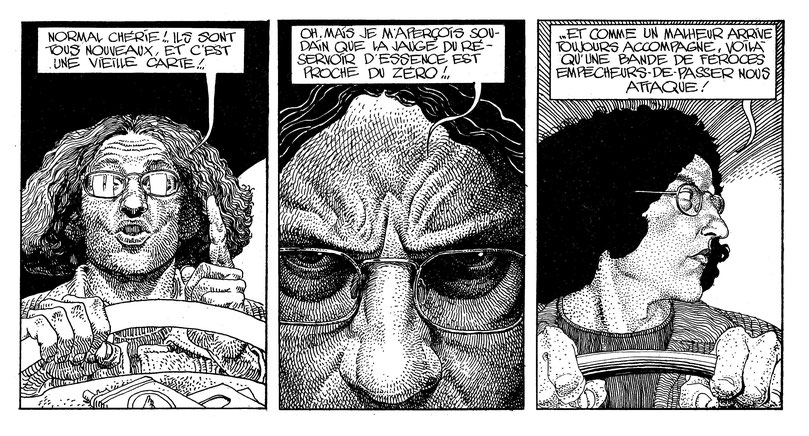

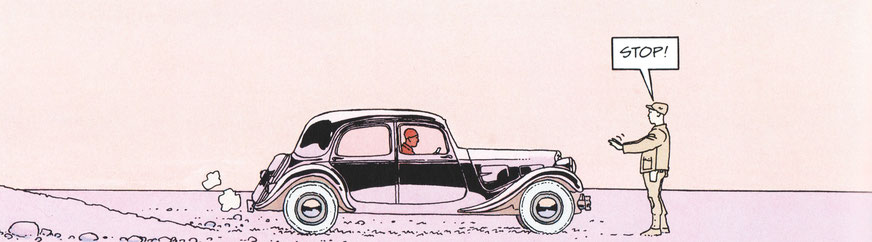

The seminal moment had been a whimsical but densely textured strip that appeared in Pilote #688 (January 11, 1973). Advertised on the cover as “a completely crazy trip with GIRAUD”, “La Déviation” (“The Detour”) would later be considered the decisive first step on the road Giraud would follow as Mœbius. In an interview with Kim Thompson in 1987, Giraud explained something of the context:

Over several years Pilote had developed what they called the “current events pages.” I had too much work to do on Blueberry... but I went to their meetings and... tried to contribute ideas... I did a couple of pages... three or four times, collaborating with various people. But the “current events” pages began to suffer from a certain sameness... My idea was that we should break the sameness. I suggested that... we could also do experimental works. The first reaction, of course, was fear: “Experimental? What does that mean?” Something obscene, or incomprehensible? The only way I could explain it was to do some, so I did “The Detour,” the theme of which, to an extent, was what I was proposing, namely to take unexplored roads... which was also a manifesto of sorts on the subject of freedom and dreams...

(Comics Journal #118, December 1987, p.94)

In notes prepared for Marvel’s reprinting of the story (MŒBIUS 2 ARZACH) Giraud also wrote that his friend Philippe Druillet had been nagging him to do a comic strip in the style—or one of the styles—he used for his sf illustrations, implying that “La Déviation” was done in response to Druillet’s urging. But everything that happens is the result of more than one cause, and Giraud told another version of the story a dozen years later:

Who said it? I no longer know. Tardi and Mandryka were there. Was I raving once more on the subject of comic strips? Did I give my opinion once too often on what one ought to do? The reply was direct, exasperated, definitive, unappealable, like a sentence: “Stop berating us with what to do. You’re there, stuck with your Blueberry. You don’t stop saying you’d like to do something else, but we never see that anything comes of it. Do it! We’ll talk about it afterwards.”

Do it! It was ringing in my ears as I made my way home. The drumming of the words broke my skull. The ancients must have felt something like this when they consulted the Delphic oracle. Do it! Two words were enough to send me back to myself, with my outbursts and my contradictions. An old schoolteacher incapable of questioning himself. That’s how my friends saw me. Had they talked to each other before speaking so bluntly? No matter. I hurried to buy a pen-holder and some paper and set to drawing La Déviation as if my life depended on it. This was the point of departure...

(Moebius/Giraud, histoire de mon double, p.161)

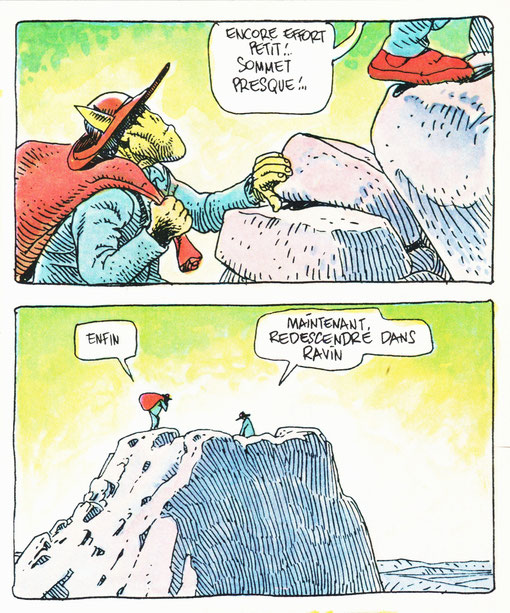

On the opening page, the story was advertised as having been drawn in pen “FROM A DISCONCERTING ABSENCE OF SCRIPT”, and he later wrote that the story “told itself, straight from my unconscious mind” (MŒBIUS 2). Le Bandard Fou likewise “came in a state of complete spontaneity”; he worked on it “at night, in small increments, while... doing Blueberry and other jobs during the day” (MŒBIUS 0 THE HORNY GOOF). He did the thirteen-page “Major Fatal” in one sitting, without a script: “I improvised as I went along, out of a sense of risk and pure fun” (MŒBIUS 3 THE AIRTIGHT GARAGE). And the Garage, in turn, would progress in a deliberately haphazard fashion into uncharted territory.

You can take your pick, but from where I stand it looks like the end of the first flowering of Mœbius is marked by the appearance of “Escale sur Pharagonescia” in Metal Hurlant #47 (January 1980). Begun in 1977, this twenty-six page story was finished in 1979, and appeared six months after the Garage had been published as a book. Thereafter, what is or is not the work of Mœbius may be argued one way or another. I’ll argue it this way:

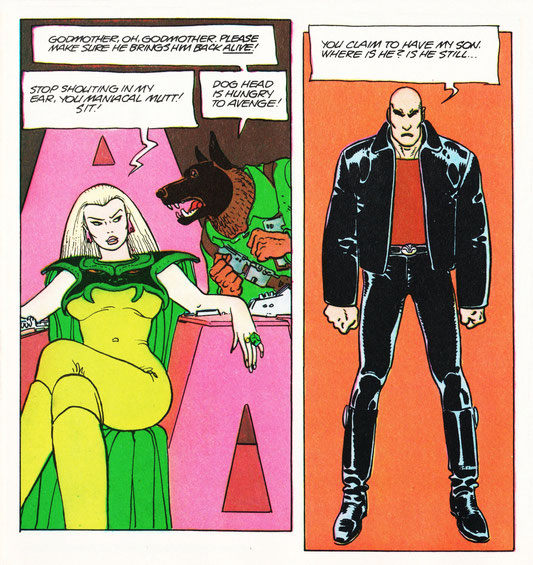

If Giraud began The Incal as Mœbius, it became, after only a handful of pages, the work of “Mœbius” in name only. It was a name he’d established and was his to use, but the Incal lacks some of the defining characteristics of the Mœbius of the preceding half-dozen years: space, for one thing, expressive and individual characterization for another. It’s derivative, second generation work: slick but cluttered; facile, occasionally spectacular, but superficial and—dare I say it?—unadventurous.

Elsewhere, Giraud—who was then embarked on a journey of personal evolution—had begun to distance himself from the “Mœbius” signature, evidently out of concern or uncertainty over negative aspects of character expressed by his work in that mode. The signature does not appear in any of the panels of Tueur de Monde (1979), which curiously and ambivalently reflects on the origin (and perhaps the limit) of the Mœbiusian adventure. He also began signing some of his work as “Jean Gir”.

The work that forged a new and positive link, in 1983, with the adventurous and exploratory aspect of his Mœbius persona was Sur l’Etoile (Upon a Star)—a fact memorialised thirteen years later in “Les Reparateurs” (“The Repairmen”), an eight-page story in which its protagonists, Stel and Atan, find Giraud in stasis, and return him to creative life.

As I’ve just demonstrated, one may split hairs over what, after 1980, is or isn’t an authentic work by Mœbius; but the fact is that everything by Mœbius (or “Mœbius”) was by Giraud. So, for the most part, I prefer to avoid controversy by the simple expedient of identifying Giraud as the author of the works in which I’ve taken an interest.

That interest, however, is focused primarily on works that may be taken to extend, develop or fulfil the artistic adventure, begun in the nineteen-seventies, that went by the name of Mœbius.