36 EXCURSIONS & EXCAVATIONS in the HERMETIC GARAGE

8: A characteristic dissociation

“I’m afraid I haven’t got one,” Alice said in a frightened tone; “there wasn’t a ticket-office where I came from.”

(Lewis Carroll, Alice Through the Looking Glass, chapter III)

One advantage of not having to pretend I’m an expert is I get to confess my ignorance, my short-sightedness, my lack of perception. For instance, when I first encountered Mœbius, I thought “Mœbius” was just a name used by Jean Giraud to sign his work, the same way he sometimes signed it “Gir”. What was the difference?

When I got a look at the early Blueberry books—Fort Navajo, Thunder in the West—they were hard to reconcile with what I’d been seeing in Heavy Metal. The stories were readable (at the time I’d have been happy to read more) and the storytelling was clean and engaging, but the art was fairly pedestrian. Obviously it was from an earlier period, and I simply supposed the Mœbius with whom I was familiar was a linear development of that earlier artist. Even when I read the later Blueberry stories published by Marvel, I didn’t quite see that Mœbius and Gir were two distinct artistic personae, operating in parallel. It was only last year, while filling in gaps in my belated collection of Metal Hurlant, that this became obvious.

Le Hors la Loi, the sixteenth Blueberry album, was the last to be serialized in Pilote (as L’Outlaw) between April and August 1973. After the next album, Angel Face, published in 1975, the series was halted by a dispute over royalties. The eighteenth, Nez Cassé, didn’t appear until 1979. It was serialized, in three parts, in Metal Hurlant, just as the Garage was coming to its end.

The contrast between Gir and Mœbius could hardly be more pronounced...

Giraud, a lover of jazz, would later write that his work as “Gir” represented the statement of the theme, whereas “Mœbius” was the improvisation. Perhaps a clearer way to make the distinction is to observe that Giraud’s work in Blueberry was done in the service of narrative, whereas his work as Mœbius, in a variety of ways, escaped its bounds. Several exhibits, by way of illustration, follow.

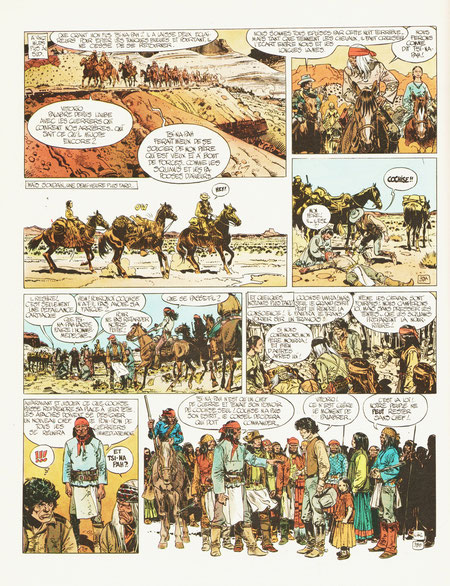

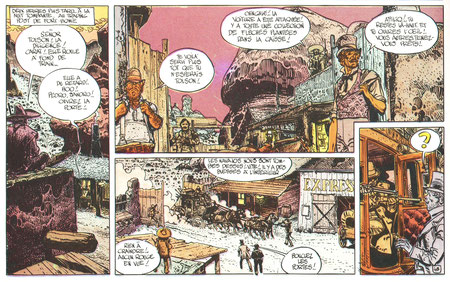

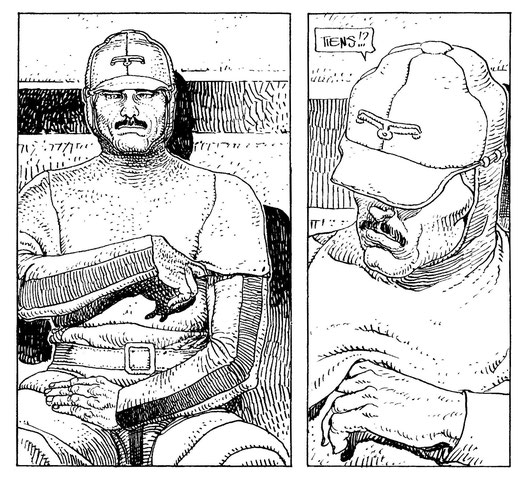

Most of Blueberry, from 1963 until 2005, when Dust was published, played out on pages whose basic framework consisted of four tiers. There were variations, but mostly they were drawn and numbered as half-boards. Here, for instance, are pages 4b and 5a from Nez Cassé, first published in Metal Hurlant #38:

As the point of view shifts, Tolson watches the stage approach, then calls for the gates to be closed when it enters the trading post. He’s then surprised to find himself facing the wrong end of a rifle. The large panel on page 5 reveals the nature of the situation, and two further panels bring into focus the specific quarrel the Apaches have with Tolson. The seven panels form a continuous sequence. All the characters are attentive to the developing action and to one another. This is fairly typical of the work of Giraud, in stories scripted by Charlier.

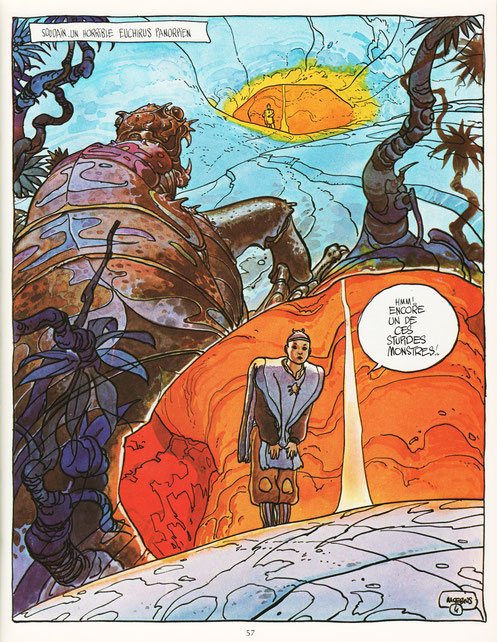

The work of Mœbius can hardly be said to lack sequences of narrative action—indeed, “L’Homme, est-il bon?” and the three Arzach stories, being mute, depend entirely upon the clarity of Giraud’s narrative control—but more in Mœbius than in Gir spills over into wonder and mystery. Consider, for instance, the fourth page of “Ballade”, from 1977:

What strikes the eye first of all as a single image is actually two successive images. In the first, a “HORRiBLE” creature is climbing toward the cave in which the story’s protagonist has settled for the night; in the second, that individual bends forward, peering down at the creature. “HMM!.. ANOTHER ONE OF THESE STUPiD MONSTERS!..” The posture indicates a placid curiosity and unconcern, yet on the next page there will be an apparently rather desperate resistance to the dangerous creature’s intrusion. Why no sign of alarm on page 4, no preparation for danger?

The same question may be posed with respect to page 8: why does Loona, the other character, seeing the unfortunate end of the story approaching from afar, do no more than announce a fatal acceptance of it? The actors in the story proceed to their appointments with an almost dreamlike detachment. It’s for me, as a reader, to feel the unsettling surprise, the shock of a rude awakening.

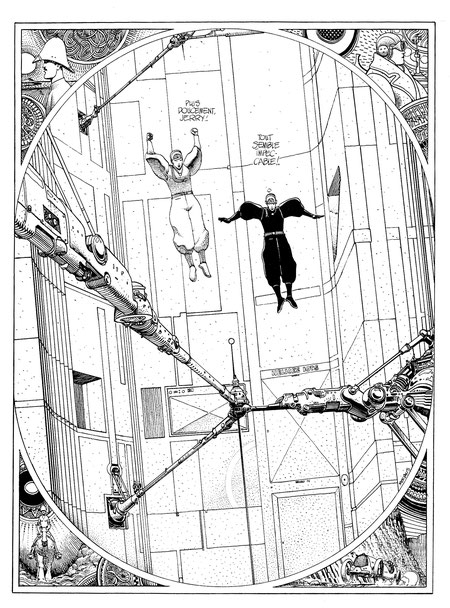

I find a similar and startling dissociation between my response to the action and the Major’s, in episode 19 of the Garage. His helmet has just been grazed by a projectile, fired by an assassin; yet he looks around as if only mildly surprised, and expressing disdain that someone might display such poor taste as to try to kill him or one of his companions. In this instance, his apparent unconcern may be open to explanation, so let me turn to an earlier example, an incident that didn’t shock me, but left me baffled.

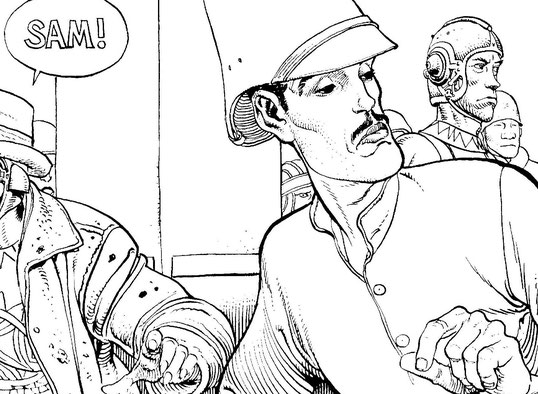

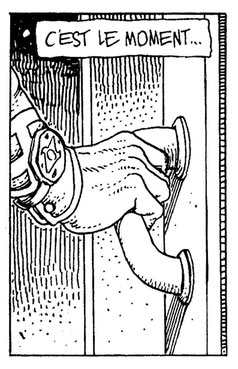

It’s a page that appears no less surprising and hardly less mysterious than when I first saw it, because the narrative turn remains thoroughly unreasonable. It begins with a small panel, a hand on a handle; the caption reads, “iT’S TiME ...” In the second panel, the Major’s spy, Sam, and his companion, Okania, are at a window on a train whose progress has been halted by a bomb. They’re watching the plane that dropped it, and the résumé (in the title panel at the end of the first tier) reminds us the train is under attack. But the second tier opens onto a full-width panel heralding the arrival of... a ticket inspector? Flanked, let it be said, by two guards.

“TiCKETS, PLEASE!..”

The three remaining panels reveal that the other passenger in the carriage—asleep until now—appears to have misplaced his ticket. Neither the inspector nor the guards seem disposed to treat the matter lightly.

The shift of attention from the bombing of the train to the business of the ticket inspector (who is indifferent or oblivious to the bombing) still troubles and delights me, because, by the end of the page, I also am more concerned by the passenger’s predicament than by what may be a terrorist attack or an act of war. The change of focus betrays an absurd lack of proportion that has a dreamlike quality.

And Sam and Okania? Let me wonder about them if I will, but they’ll be absent from the narrative for a while to come, and I’ll never be told explicitly what happened next...