“I’ve got an appointment with a humanoid in Bolzedura. His name’s Grubert...”

Rediscovering Mœbius – a reading of “Major Fatal”

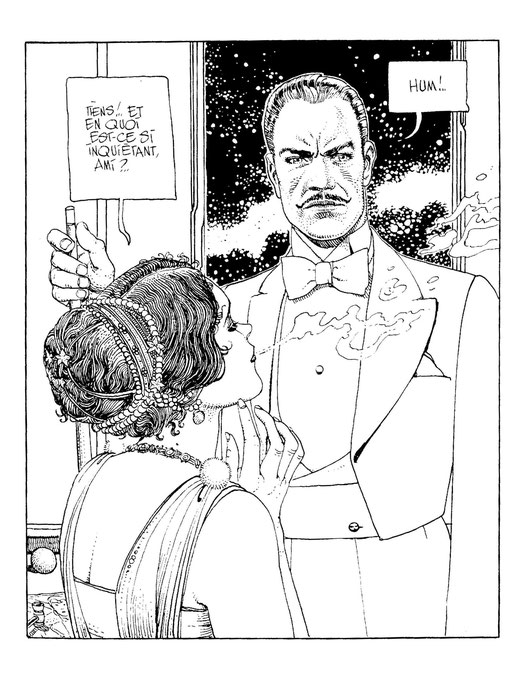

I remember the strong impression created by some of the early chapters of what was then known as The Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius. It was 1978, and the first chapter I saw was the fifth. It was incomprehensible, but fascinating. Someone was resting a finger on a photograph of Jerry Cornelius, then there were a couple of panels that looked like they might have belonged in a glossy nineteen-thirties movie melodrama. (As it turns out, they probably did.) On the following page, two panels seemed to be set in something like a railway carriage. The last panel showed a giant blimp-wheeled truck racing across a desert. The draughtsmanship was exquisite, it was entirely mysterious.

Over the next couple of years I gathered together as many chapters as I could find in the early issues of Heavy Metal, but I never found them all. There was always something missing and, fascinating though it was, The Airtight Garage remained elusive. So when it was published as a book nearly a decade later, I bought it because it was unfinished business.

But it was a different time. I’d changed. What I saw collected in the book seemed remote. I had things on my mind, I was busy. (It happens to most of us.) And, after the intense colors of Arzach—I’d found a copy of the French hardcover album not long after I came across Heavy Metal—I wasn’t sure the often flat and pastel tones of the book were an improvement over the clean black & white of the original. I can’t even recall that I read it in its entirety. Possibly I just kept thumbing the pages and thinking, “One day, one day...”

And, by and by, it got silted up, buried in drifts of time, and my interest in this curious work became a thing of the past.

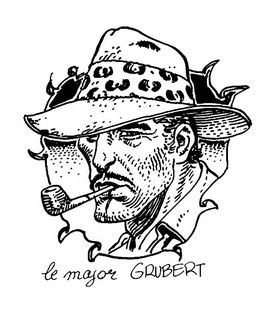

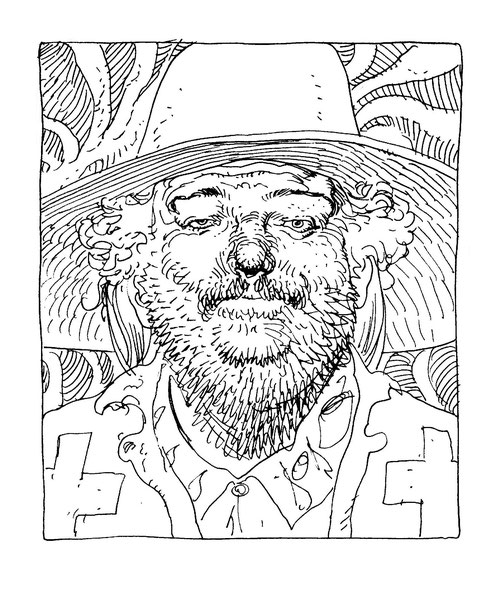

Then, in 2018, I picked up, in a store, a copy of the Dark Horse edition of Inside Mœbius volume 1. It was sealed; all I could do was look at the cover, showing the diminuitive figure of Major Grubert holding a smoking gun—a pistol, not a rifle—one foot planted on the body of the artist. Not The Airtight Garage, for sure, but enough to rekindle, after all these years, my dormant engagement with the work of the artist known as Mœbius. I bought the other two volumes as they came out—hurrah for Dark Horse!—then gave in and bought The World of Edena, which Dark Horse had published a couple of years earlier. Then I gave in and bought The Art of Edena, because I was feeling an itch, a hunger. Never too late to get hooked.

And maybe never too late to roll back forty years and wonder what was it in The Airtight Garage that so fascinated me? So after a few weeks of looking on eBay, I found a copy that wasn’t outrageously priced, and started with the opening story, the immediate precursor to the Garage—its “prototype”, as the artist later called it.

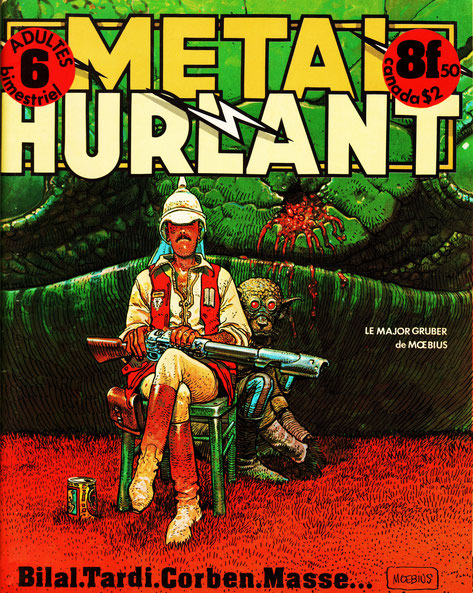

As it happens, the first episode of Le Garage Hermétique appeared in the same issue of Metal Hurlant as “Le Major Fatal”, and may have been drawn before its ostensible precursor; but Major Grubert is not present in the first two episodes of the “grand feuilleton à suivre en bandes dessinées” that began in that issue; and, as Giraud later wrote, it was

only with the third chapter that I began picking up the loose ends and giving the story a direction. That’s when I brought back Major Grubert, for instance...

(Introduction to “the Airtight Garage”, 1987)

And I was surprised when I read “Major Fatal”, not least because I enjoyed it enormously. My only recollection had been that when I’d tried to read it thirty-odd years earlier, as part of the book, I found it opaque and whimsical. Maybe I’ve grown more whimsical myself as the years have passed—a defense mechanism, I suppose. But enchantment opens doors: the sun was shining, and the story welcomed me. I felt happy. It would hardly be accurate to say I was seduced by the plot, but I was charmed by the artist’s approach. I saw the humor to which I hadn’t responded first time round; and it was, moreover, a humor that didn’t undercut my delight in the fantasy. I felt Giraud was affectionate rather than cynical as he playfully scattered an assortment of familiar clichés across the pages. And I had the curious sense of being an onlooker, closely attending to the act of making of a story—a privileged witness to a peculiar form of narrative creation, unstable despite the familiarity of its devices.

In what follows, I do little more than attempt to trace, in an approximate way, the main lines of my delight. It’s a reading, not an analysis—I draw no conclusions—but it ought, at least, to supply an illustration if not an explanation (for those who, like my younger self, don’t get it) of the fact that “Major Fatal” might be read with pleasure. I’m not, of course, advancing an argument that it must be read with pleasure; nor suggesting that the ability to read it with pleasure requires a degree of refinement or perception lacking in those who fail to enjoy it. I’m merely airing a small happiness—rare enough for me, these days—and sharing with others who may have delighted in the story my belated appreciation, and an opportunity to compare notes.

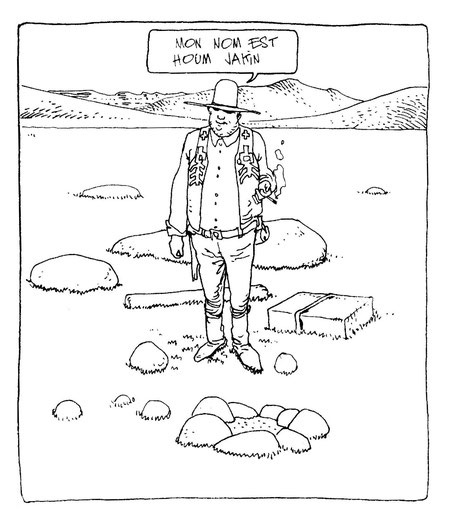

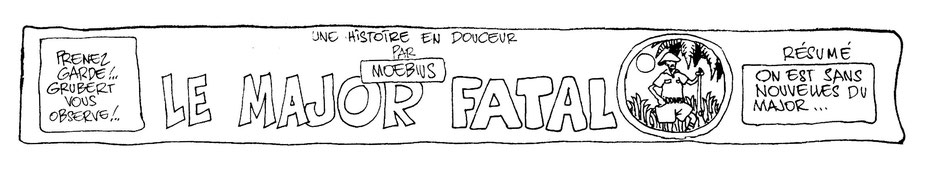

It’s a story that draws attention to its medium, its narrational circumstance, first of all by titling its pages. The first page is titled, simply,

FIRST PAGE

The story is also characterized (perhaps incongruously or misleadingly) in the English translation, as

“a sweet story”

—“une histoire en douceur.”

Perhaps a less confusing translation would be “a pleasant story” or “a pleasing story”; but to proceed “en douceur” is to proceed cautiously or carefully, so, better yet, “a cautionary tale”? Indeed, a warning is announced to the left of the title:

“Beware! Grubert is watching you!”

Major Grubert is not the main focus of the story, but he’s the pivot on which the plot (or mock-plot, as it happens) turns; and already, as a reader, the tables are turned on me. I’m warned I’m being watched by someone I’ll be watching for—someone who is, moreover, a hunter.

So, at least, he was pictured on the front cover of the magazine in which the story first appeared; and, rather more whimsically, there’s a tiny cameo to the right of the title, of Grubert in hunter-with-foot-upon-kill pose, beside which I find

“The story so far:”

—the “résumé ”. Even as the story begins, I find myself in the middle of things. What have I missed? What don’t I know? I may know this is only a bit of fooling, but it puts me on alert: prepares me for the tension of continuity, the entanglements of a plot already underway.

On the other hand, of what does this résumé consist ?

“No news from the major today...”

Or is it possible we have (“on est sans nouvelles du Major”) no news of the Major?

It tells me little except, perhaps, that the continuity involves being prepared for something concerning the Major—that, somehow, this is what I ought to be waiting for.

But let me not evade the issue: this is also flat out and obvious absurdism. The story so far is that there’s no news. That doesn’t necessarily mean good news. Nothing from Godot either, I suppose.

In any case, the story begins—and begins in what might be the American southwest, sometime around 1900, by the looks of the first panel. But the character who introduces himself in the first panel as Houm Jakin disabuses me of this notion by quickly flooding the story with background. This somewhat paunchy scout is, he tells me,

“Lord of the Carn Finehac,”

So, in addition to his name, I now have a title—a title redolent of power. And what is the “Carn Finehac”? Something, in stories of this sort—fantasy adventures—which I may soon discover, even if I do not discover all.

Or, since this is a continuity—a mock-continuity—something I ought to know already, or, at least, to be able to put in context. (Well, haven’t I?)

“south of here, in the onyx zones.”

And here, in addition to name, title, and the mysterious “Carn”, I am offered a double orientation, one of which (“south”) is commonplace, and one of which again announces regions of fantasy. I may not know where the onyx zones are, but by knowing there are onyx zones, I know I’m in the realm of invented worlds—on a world somewhat like our own, but not our own.

“We’re wasting away, there.”

Houm, though alone when I encounter him, is not a singular being: his “we” presumes a people, a history; and that history has evidently arrived at a point at which they—whoever they are, and however many—are “wasting away”.

Wasting away in what sense? Wasting away, there. So they’re isolated, or separated from something. Cultural isolation?

Or is there something they would do, which they can’t, in order to make manifest some form of growth or expansion? And does that expansion imply an imperial situation—a power that might enforce its growth at the expense of something or someone else? Houm announces himself as “Lord” of the Carn Finehac, after all—though he looks humble enough. And, perhaps for this reason, it’s easy to mistake him for (or identify him as) the hero of the story.

Certainly, the situation he announces has need of a hero. This is what he tells me, and what I’m ready to hear when he says,

“The junction’s been suspended so long now...”

So, yes, they’re cut off in some way. But the “junction”...? An ordinary word; but, in an extraordinary context, does it suggest a point of contact between worlds? Certainly, Houm and his people appear to depend on this “junction”. And

“pretty soon, it’ll be too late ...”

Now, this is the kind of urgency that launches an adventure...

“... we’ll enter a period of irreversible decadence.”

... a heroic quest to rescue a people from their doom. Here the epochal scale of Houm’s concerns and the context of the plot become explicit, and

“Already the Bakalites’ magic exceeds ours ...”

So the weakness of Houm’s people is weighed against the power of others. I now find myself on the inside of a fantasy that sustains identity—“we”, “ours”—in relation to intertribal, international or interplanetary conflict, and the stage is set for the actions of the hero. He has an opponent, an enemy—an other. And I’m still only in the second panel.

“Anyway, that’s what the scroll readers say...”

Are scroll readers part of a ritual hierarchy? Is prophecy involved? I’ll soon discover that a scroll reader is an electronic device. This does not, however, rule out its ritual or magical character (see pages 4 and 5).

Panel three brings the nature of the adventure fully into focus:

“I’m going to Bolzedura,”

Another invented name, hurrah, thickening this invented world...

“the forgotten city,”

... and the obscure thickness of its history. A city “forgotten” (or forsaken—“abandonnée”) on our own world already involves us in the remote and unknown enterprise of a people, their long-past eclipse or scattering, their loss to time (amid the rise of other cultures, other histories), and the indifference of nature. Ah, the romance of recovering, from that obscurity, some knowledge of these people. Or haunting their long-vanished footsteps with our gaze. But, in such a case, these are people who have vanished into the shadows of a world we imagine we know, or a world we suppose may be known. How much greater the romance when we must recover such knowledge from a world, or plurality of worlds, immersed in the unknown?

Nonsense, you object. Such worlds in the realms of fantasy do little more, at best, than mimic (often not very well) the structure of cultures and histories already submerged in the past of our own world. They are the flimsiest of inventions, and insubstantial.

Yet I know that, in my past—the time of my own growth as an individual—I delightedly turned to such fictions, with a willingness (however temporary) to imagine them more substantial than they were. In such imaginings, the bloom of discovery was not yet restrained by the knowable, the recognized. And did I not persist in returning to such imaginings until at last I was obliged to concede there were no discoveries to be made that had not been made?—or, at least, to acknowledge that, if there were, they would be made by others, and perhaps would not greatly interest me. I've been forced to admit to myself that to glory in the hope and dream of such discoveries is to cling to childhood, to the ignorance of childhood, in defiance of what I’ve learned. And surely I ought to know that what I’ve learned forbids me the luxury of not knowing. Isn’t it time to acknowledge I can no longer be a child?

Yet what did I want, as a child, but to know? I was hungry to know, I kept asking questions. Is there nothing in this forsaken city for me? There is, at least, the recognition of what, once, I longed for—and what, now, I recognize as only a cliché, a facade. But even this empty glamor, this play of surface, presents an opportunity not only to remember, but to explore, and irony opens a door to self-awareness even as all the old plots come tumbling in:

“to try to find a new junctor...”

A quest, in search of renewal—of renewed connection. The suspended “junction” has now gained an agent, a means of its production, the motive force of plot—Hitchock’s “McGuffin”, which sets the plot in motion—a necessary device...

“in spite of an old Bakalite with terrible powers.”

... and an enemy, to be overcome. What are his terrible powers? It’s enough, at this stage, to know they are terrible. Did he survive to be old because of his terrible powers, or are the terrible powers a consequence of his age? And what is a Bakalite, anyway?

(The Shorter Oxford Dictionary reminds me that Bakelite is the “(Proprietary name for) a characteristically dark brown thermosetting plastic made by copolymerization of a phenol with formaldehyde.” Obviously, this is not quite the answer I am seeking.)

“Many have already died...”

The danger of the quest is advertised: the tide of time washes its would-be heroes, repeatedly, against the sands of disaster and ruin. And here before me is yet another hero—the one the story provides for me to follow. The aim of the quest, whatever its ostensible purpose, is to recover life from inevitable death.

The fourth panel extends its difficulty:

“In three days, I’ll see the high towers of Platmol...”

But I shall not see these towers—though Platmol, for a moment, looms in my path, like the distant cities Lovecraft saw in the sunsets of his dreams, or in the early stories of Dunsany, which were perhaps their inspiration. Bolzedura, meanwhile,

“and its old Bakalite will still be very far away!”

So the quest is to be long. I’ll find out how long on page 6; but the reason for the length of the journey is evident on this first page. Houm, like knights of old, is making the journey on horseback. Or not quite—because what he’s riding is not quite a horse:

“We’ve created these creatures to mimic the famous “horses” of Earth...”

There’s very little on the first page to tell me, visually, that we’re not on Earth, and that this is not an offshoot of Charlier/Giraud’s Blueberry, overwritten (in both senses) by a science fiction plot. Everything in the exposed mechanics of plot and setting—if I discount the slightly strange horse in the fourth panel, is inscribed in Houm Jakin’s monologue, so the ironic nature of this clotted science-fictional background is emphasised by being “spoken” in the context of something that looks recognizably (if approximately) historical. The invented fantasy is verbalized in the space of a representation that I might take for a representation of the real, and the fantastic nature of science-fiction, along with the dependence of fantasy on language, are evident.

In the common world, whatever our differences and misunderstandings, there are some things we take as being commonplace. We need only say the sun rises, in order to indicate a common experience. But the world in which two suns rise must be invented, and its story told. I once had an appetite for such stories, and have been delighted by them. I’m reading one now. But I’m also conscious here of only being told we are not on Earth.

I'm also being told that Earth is far away—with the implication that here is also an untold history (such as I have seen invented many times) of mankind leaving Earth and extending into the star-filled sky to find a new home. All this happened long ago, and Houm’s people (whom I shall never meet), though now on the brink of decadence, had (or still have) the power to make a “horse” to mimic the creatures on their faraway, fabled (?) ancestral (?) home.

Why make something like a horse?

Nostalgia? A hedge against alienation? An effort to make real a tradition in order to stabilise a self-identity at risk in a universe so vast that the very notion of “home” is absurd?—for otherwise they might feel themselves to be creatures without a center. Or is the loss of centeredness, of self-identity, this nostalgia, this mimicry of an imagined distant homeland itself a symptom of the decadence, the “wasting away”, that threatens to become irreversible?

The second page is titled

THE AMBUSH

Was it Raymond Chandler who suggested that, when a story sags, it’s useful to have a man walk in with a gun?

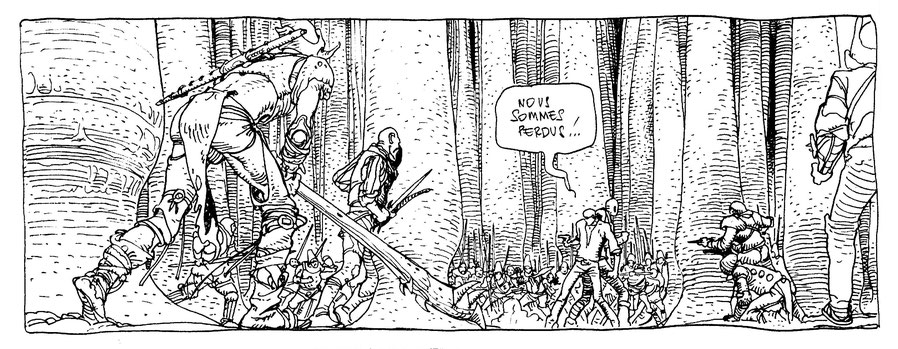

One consequence of this, in cultural terms, is that we may grow bored if a man doesn’t walk in with a gun. But let me not carp. An ambush is advertised by the title of the second page and by the first panel: on the left, hidden by a tree trunk, a man with a gun waits for Houm Jakin.

Well, not quite a man—he has almost no nose. And the gun is a science-fiction gun. In narrative terms, the situation is immediately gripping. But the second panel just as immediately places that situation at an ironic distance, as Houm Jakin thinks,

“Well, if it ain’t that charming Boaz fella,”

“ce cher Boaz”

“trying to lay one of his deadly ambushes again ...”

Jakin is evidently unconcerned. Gripped by suspense, alert to the advertised danger, I, as a reader, am often a victim—usually willing—of a sleight-of-hand. Heroes are frequently conventional, and the dangers they succeed in overcoming exceed what I might reasonably expect to survive. Their successes affirm my admiration for them, even when the dangers (and the powers of the hero likewise) are exaggerated beyond credibility. What a child I am, to be so regularly seduced by such a trick.

But the whimsicality of the presentation here exposes the sleight-of-hand: Jakin is evidently more powerful than he looks, and secure in his power. I may not know what he has up his sleeve, but I know he has something up his sleeve.

Also: that Boaz is “trying to” lay a deadly ambush advertises his lack of success; “again” his prior and perhaps persistent lack of success. Jachin and Boaz are the biblical names of pillars in Solomon’s temple, so is it being hinted that these two adversaries are formally bound together in a perpetual opposition, like Ignatz and Krazy, in order to sustain the readers of such stories?

“When will you learn?”

asks Jakin of Boaz. But the question is perhaps rhetorical, for the recurrent stereotypical villains of popular culture never learn. They bring themselves to the fray, time and again, to be frustrated and foiled, so that a thoughtless audience, immersed in a historical situation about which it doesn’t want to think, can satisfy itself with the dream that all is right, or can be made right.

Of course, these days, that has begun to change, as an argument goes on over whether we can have faith in our heroes, or whether our heroes are heroes at all—and, more to the point, as we argue over whether all can be made right, or whether the world in which we live is irremediably injured.

But let me attend to this encounter, which had its origin in times no more innocent, but in which the expression of innocent hopes (or the recollection of such hopes) were still part of the common culture. In the original French, Jakin asks, “Mais, quand cesseras-tu?” When will you stop? When will you give this up?

“You’re not welcome on this planet...”

says Boaz to Jakin. (Or “not wanted”.) By the time he drew this, Jean Giraud had been drawing stories set in the American west for more than a decade. Europeans had overrun the continent, changing it irreversibly, dispossessing its inhabitants. The resistance and hostility of the natives became part of the entertainment of those who had taken the country, and the forms of that entertainment were exported. Giraud was by no means unconscious of or unsympathetic to those who had been disposessed. He was also a reader of science-fiction, where this affirmative conflict, with heroes representing the winners, was often replayed. (There were, of course, exceptions—but a culture of winners tends, inevitably, to misread or ignore or forget the exceptions.)

Europeans had also spread south and east, encountering cultures—and the remnants of cultures—remote and older than their own. Other colonial trajectories inform this adventure:

Things have indeed changed on Syldaine-Cygnoos...

The planet now has a name. In the original, “Syldain-Dolchigne”. Since cygne is a swan, and chignon a coil or knot of hair, I suspect that an obscure pun or elusive idiom (such as “D.A.” for swept back hair) may be here given a hopeless but playful translation. I don’t know. Anyway, I’m confronted by the implication of a history—things have changed, they are not as they were.

How they were I may not know, but these hints and echoes of an unknown past litter the foreground of the action...

... a traveler often falls prey to a melancholic Cyd’berg ... as is now the case with Houm, who faces Boaz ...

... but this, at least, I do know. Once, Houm’s people were strong enough to be secure in their travels. No longer. The empire, if that’s what it was, is in decline. Its inhabitants are no longer safe when they go from here to there, and this signifies a loss of power.

And yet, not perhaps a resurgence of the dispossessed. If I detect a nostalgic note in Houm Jakin’s equipage, and his quest, Boaz is also characterized as “melanco”. Both are possessed by the sadness of things lost. In the third panel, Boaz is allowed to make a speech:

“You’re headed for Bolzedura ... to disturb its silence...”

Not only is the city forgotten. It is, as the original French made clearer, abandoned. But its abandonment is, for Boaz, something to be respected, not desecrated, not violated:

“... to ransack its memory walls...”

A. E. van Vogt’s principle of writing science-fiction involved using language and a set of terms in such a way that the difference of the world of the story from the common world of experience was kept constantly before the reader. Here we have “memory walls”, which may be more, or no more, than illustrated tableaux or library shelves. It hardly matters. At this moment, I am alienated from my certainty, I look toward discovery.

“... to destroy the delicate forms of the city of honey!”

Ah. Is this why the story is a “sweet” story?—sweetness stored up, as food for the young. The golden age of science-fiction is twelve years old. (The language of the story looks back, from the mid-nineteen seventies, when science-fiction was beginning to emerge, if not yet fully, as a viable popular category, to a time when it was more marginal. The heroes from that earlier time shared the shelves and racks with those riding the new wave.) In the story, however, those for whom the stores were laid up are no more. The delicate forms of this golden city are precarious. Those who feed on it are not those who were intended to feed on it, but aliens. (This not long after a time—the nineteen sixties—when the young were aliens, and the culture was transformed by their alienation.)

“I’m going to scatter your atoms...”

A classic threat...

“... with my S.W.F....”

What does that stand for, I wonder?

“... to teach you a lesson!”

Notwithstanding the cheap pulp dynamics of much science-fiction, it retained for many years an aura of didacticism inherited from Hugo Gernsback, and a loose aspirational alliance with technological progress. To teach someone a lesson, however, implies their situation in a hierarchy of knowledge or power, and a reformation of their behavior. Boaz’s threat is made absurd by the fact that he intends to turn H. J. “into a little pink cloud ...!” What might one be said to learn from that?

He ends the page with:

“Damn you, Houm! My heart seethes with hatred! I’m going to kill you ...!”

Or, more accurately, “Damn it... My heart is full of hate!..” Something of a surprise, then, that the third page is titled,

AN ORATORY JOUST

signalling that speech, rather than mindless action, may resolve this conflict; but fitting, in that words rather than images sketch out and sustain the development of the narrative. And, indeed, rather than a duel, the exchange on the next two pages represents an almost collaborative consolidation and extension of the plot. Jakin addresses his would-be assassin as “my dear Boaz” and asks Boaz to “Listen to the reasons for my journey”. He tells him:

Yes, Grubert. The same Grubert I’ve been warned is watching me. The same figure as on the cover of Metal Hurlant 6, who’s pictured in cameo in pith helmet alongside the title on page 1.

But what do I know about him? There was no reason I should know, as I read this, that in a previous incarnation (“The Hunt for the Vacationing Frenchman”) he was not merely an absurd character, but exaggeratedly comic—a parody of the big game hunter, preposterously in quest of a camera-wielding tourist:

Despite the ironic and whimsical aspects of this story, this will not be his character here.

But I don’t know anything yet. That he’s a “humanoid” tells us more about the world he inhabits than about Grubert, but Jakin asserts that

“he can help me find a compromise with the Bakalite.”

—the “old Bakalite” with terrible powers. So what does this tell me? That the Major wields or represents some political power? Boaz appears not to be convinced:

“Impossible! The Major is a megalomaniac impostor! ...”

An interesting and definitive combination. The Major may well claim political influence, and Boaz appears to know of him, so he has some prominence or reputation—but is his rank anything more than a mask, a pretence? Are those who claim influence only frauds and manipulators, motivated by ego, whose success is founded on the illusion that they are what they say they are? Is Grubert who Jakin hopes he might be?

Boaz’s argument that he is not, however, appears founded on the premise that the figure of the Bakalite represents an immutable role, from which consequences may be deduced:

“No one can find a compromise with the Bakalite who is, by nature, uncompromising!”

I wouldn’t presume to know, at this stage, anything about the nature of the Bakalite, nor whether Boaz’s argument is specious. It sounds, rather, as if the Bakalite’s role may be as fixed and stereotypical as that of Jakin and Boaz. Jakin, however, disagrees about the Bakalite’s nature—or is he disagreeing about Boaz’s characterization of the Major?—while indicating further complexities that lie in the background of this colonial or post-colonial history:

“No, he isn’t. That’s a bunch of lies from Terran propaganda.”

Probably he’s referring to the Bakalite—unless the mysterious Major is not himself a Terran. Hmmm. And here, perhaps, I find myself slightly alienated from the Terran point of view natural to me, when I realize that, in this story, the Terran position may be sustained, dishonorably, by lies.

Of course, I’m not such an innocent that I don’t know this may be so—but I’m a slow learner. And in order to read a story (no matter what the theorists of genre pretend) one must be prepared to re-learn the ground rules each time one begins.

At this point, Jakin makes a surprising offer:

“Come with me ... We’ll fix my scroll reader and face the Bakalite together.”

Still Boaz resists. “Tsk, tsk ...” he says, as if Jakin’s suggestion is somehow improper. And again backs up his position by an appeal to an immutable role—this time, his own:

“I’m Boaz, Cyd’berg assassin! The only thing that pleases me is to lay an ambush and kill colonists...”

... the role he was given on the preceding page. He’s still under the illusion that he is as he was created. He has not yet embraced the ongoing existential quest of becoming. Jakin challenges his fixity of purpose by telling him to

“Beware the Muller-Seltzer effect, my dear Boaz!”

What is the Muller-Seltzer effect? I can’t even remember, in these, the days of my decline, what the Muller-Fokker effect was. Anyway, Boaz continues to resist, insisting on the fixity of his role:

“A Cyd-berg assassin fears nothing!”

The irony of the declarative fixity of purpose, by which characters in the crudest adventures identify themselves, here generates a further irony, discernible in a history to which these two characters have no access:

The filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky, by engaging Jean Giraud to help design his projected movie version of Frank Herbert’s Dune, was instrumental in the development of the artist known as Mœbius. It’s fair to say that Mœbius, with his exploded and recursive worlds, had been waiting to be born for some time; but out of the deserts of Mexico and Arrakis he emerged in the mid-seventies, trailing alien spaces and an artistic quest for existential self-creation: here’s the setting, here are the characters, the costumes, the creatures, here’s the plot—what’s it all about? In relation to the origins of Major Grubert, Giraud/Mœbius later wrote:

I did Major Fatal in one sitting, without a script. I improvised as I went along, out of a sense of risk and pure fun... It’s one of the few stories of the times where, when I look at it, I still feel a sense of true freedom and an immense joy.

After the collapse of the Dune project, and with the onset of paralysis in his career as a director, Jodorowsky would be drawn to a career in comics—including the creation of what would be a six book series in collaboration with Mœbius: The Incal. The irony is that, despite Giraud’s craft and professionalism, that series constitutes a significant step backward from the Mœbius of “Major Fatal”, The Airtight Garage, and even from the brief but influential piece of sf-noir written by Dan O’Bannon, “the Long Tomorrow”. When the Metabaron made his appearance in The Incal, he, no less than Boaz, was a creature of preposterous plot, a stereotyped cliché—and he would remain so throughout. Despite the transformations foisted upon him, the Metabaron remained securely imprisoned (not least by the style in which he was drawn) within the puppet show of which he was a part, prevented forever from becoming a character, or revealing the character of his illustrator. Boaz, by comparison, belongs to a tremulous moment, alive with possibility, with the potential for (as the title of the fourth page tells me)

A REVELATION

A revelation which, in this case, turns out to be absurd in two ways. Houm, who in the first (wordless) panel of this page looks a little like a chubby Philip K. Dick (perhaps pretending to be Gabby Hayes), in the second panel gets down off his “horse” to explain to Boaz the Muller-Seltzer effect. In the third panel, planting feet wide apart in a stable but confrontational pose (but with a fixed smile on his face) he explains. And Boaz (still holding his gun) is persuaded.

The “explanation”, though clothed in pseudo-scientific language—

“an atomized body forms an active nuclear chain, and its loose but tenacious nexus...”

—is effectively that if Boaz kills him, Houm will return to haunt him and drive him crazy. The linguistic transfer of old narrative tropes to a science-fiction setting defines “space opera”—a term derivative of “horse opera” as a term for a western, which this story continues to resemble.

Boaz, whose conscience may have been troubling him—

“Hmm ... that would explain many things”

—is mollified, and finds a second dimension of action. His suggestion extends the linguistic creation of the plot:

“Show me your scroll reader. I have some knowledge of the sacred electronics...”

The “scroll reader” mentioned on the first page is now identified as an electronic device; and reference to the “sacred electronics” sounds another common science-fiction note that often signifies decadence: the confounding of technology with religion or magic.

The title of page 5 announces a major development:

THE ALLIANCE OF HEROES

which is another surprise. Given the the announced fixity of Boaz’s role. I didn’t have him pegged as a “hero”.

But the situation is familiar enough (think Robin Hood and Little John) and comforting (those who are presently our enemies may become our friends and allies). Boaz discovers that Houm’s scroll reader has a fault, and proposes that they travel together:

“With our powers united, we might have a chance to defeat the Bakalite ...”

Houm, however, appears to remain hopeful that conflict may not be necessary:

“I still have faith in this Grubert fellow ...”

I have no idea, of course, what Houm knows about Grubert, or how their meeting was arranged—but I’m beginning to suspect that, while Houm protests this faith, he’s not entirely sure.

At last, in the fourth panel of the fifth page, the long trek to Bolzedura resumes. And when I turn to page 6,

MACHINES IN THE GRASS

(more ruin, more decadence) I’m confronted by a caption that reads,

And after a journey of ten months ...

Well, why not? The essence of the story is to tell the essential story. The quest, the meeting and the adventure in Bolzedura are essential, but (whether arduous or dull) not the journey. The rudeness of this elision reminds me of some old, spare tale—something from the Thousand and One Nights perhaps—whose marvels require no excess of setting, or some old chronicle. But, again, let me not pretend that this casual skip, this airy dismissal of ten months, is not whimsical.

And it is a skip—or a leap, or a lunge. The first five pages consisted of a brief introduction followed by a single scene. Now things are beginning to move. In the first of two panels on this page, at last I see the signs of decadence, failure and abandonment—ruined walls and windows, grass in the streets of the city—at which the story has determinedly pointed.

And, surprisingly, in the second panel, I catch a glimpse of

Grubert, the famous Major ...

watching the two travelers from somewhere above. As reader, I’m looking down on all of them, watching Grubert watching them. His face is averted. I see his helmet. I see more of his neck than his face. That he is letting Houm and Boaz pass below appears to suggest he has his own plans; he knew Houm was coming, but shows no sign of wishing to meet him. Hmmm...

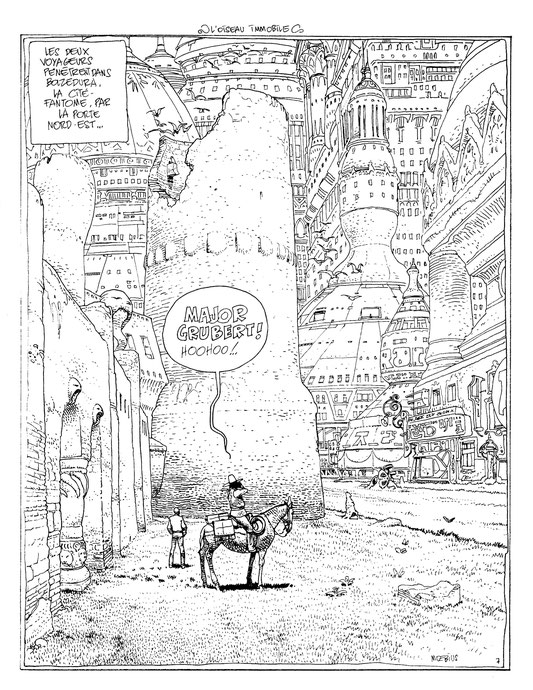

On page 7,

THE MOTIONLESS BIRD

a full-page panel situating Houm and Boaz inside

Bolzedura, the ghost city

Houm calls out, unavailingly, to the Major. It’s a large city, impressive and ornate—reminiscent, perhaps of one of Frank Paul’s early science-fiction cities. Pause a moment, and consider its silence...

Looking back, this turns out to be the still point at the center of the story. The balance has already shifted—the Major is behind, no longer a figure in whom I, along with Houm, may place my hopes—and things are starting to happen. As soon as I arrive on page 8, ominously entitled

THE TRAP

I find Boaz leading Houm through the sewers (he knows them well) while Houm concedes,

“You were right about Grubert ... He’s abandoned us.”

These sudden shifts are unsettling, but it’s as it should be. This is an adventure. What kind of adventure is it if I know what will happen?

The Major, whose presence was expected, is now a sinister absence. And the two heroes,

under the city

—in sewers dry for who knows how many years or centuries (but still, conveniently, well lighted)—are prosecuting their search for a junctor, when, in the third panel, the lights go out.

“It’s the Bakalite!”

declares Houm.

“He’s got us!”

Such things happen to heroes. I fear for them, reflexively, as I’ve been fearing for the heroes to whom such things happen since I began seeing and reading such stories. Yes, indeed, the Bakalite has got them. He turns up in the next panel to tell them so. His absurd birdlike companions tell them so, too.

And the Bakalite, dressed, by the looks of things, against the cold—are those ear muffs?—appears to be humanoid; but all I can really see, apart from the tip of a foot in the fourth panel, and a tiny, clawlike hand in the fifth, is his face, which is somewhat suggestive of a wrinkled fruit.

“You degenerate humanoids ... !”

he says, in typically villainous fashion.

“Junctor thieves ... !”

Did they really intend to steal a junctor, I wonder? And has the Bakalite any right to be proprietorial in this matter?

There are two issues here. One is a matter of translation. I notice that on the first page, in the English of 1987, Houm announced his intention “to find a new junctor”, whereas in French he’s going to Bolzedura “tenter de découvrir le joncteur”—to try to find the junctor. No indication in the original of the possibility of finding another or a new junctor. Here on page 8, in the translation, Houm recalls a saying: “A junctor in the hand is worth ten in the bush!”—an adaptation of a proverb in English, but not strictly appropriate to this situation, because Jakin and Boaz do not have a junctor to hand. The original French underlines more clearly the value of a junctor, with Houm saying, “a [or “one”] good junctor... a thousand years of happiness!” In addition, he follows this up with “N’importe quoi...”—but my French isn’t up to being certain this reinforces what he says (as if it might be translated as “whatever happens” or “come what may”) or whether it’s no more than a verbal shrug (suggesting a note of fatalism or resignation). The point, however, is that if there’s only one junctor available, then perhaps the Bakalite is justified in his suspicions. Whether he’s the rightful owner of the junctor I don’t know; but junctors are evidently precious and rare. Possession of a junctor confers power. Therefore proprietorship is sought, and contested—and some who contest may resent others who might deprive them of the power they think of as rightfully theirs.

In any case, the Bakalite appears powerful enough. On page 9,

FLOWERS EVERYWHERE

he has merely to raise a hand to banish Jakin and Boaz to another place. Very magical. They reappear on a piece of open ground (I don’t know where), unnoticed (for the moment) by groups of figures on all sides.

“Blangels ... !”

says Boaz.

“Thousands of blangels ... ! We’re doomed!”

I don’t know what blangels (begnanges) are—nuns?—or why Boaz considers the situation dangerous. A tremor of expectation rather than imagination is excited. But Houm reckons they can make an escape and, by the next panel, they have:

And after a mad flight ...

—a merely verbal, unwitnessed flight—they find themselves looking anxiously at

“Flowers everywhere!”

But the panel is so tightly cropped that only a few are visible in the background.

The story started by foisting a thickly fanciful verbal background on a superficially commonplace visual foreground. Now even the action signalled by the words is taking place between panels that otherwise have no connection. At some point, our heroes have acquired and—for one panel only—donned stylish polo-neck sweaters. Did I mention that Houm is now entirely bald?

Houm claims to know this place:

“... it’s evil”

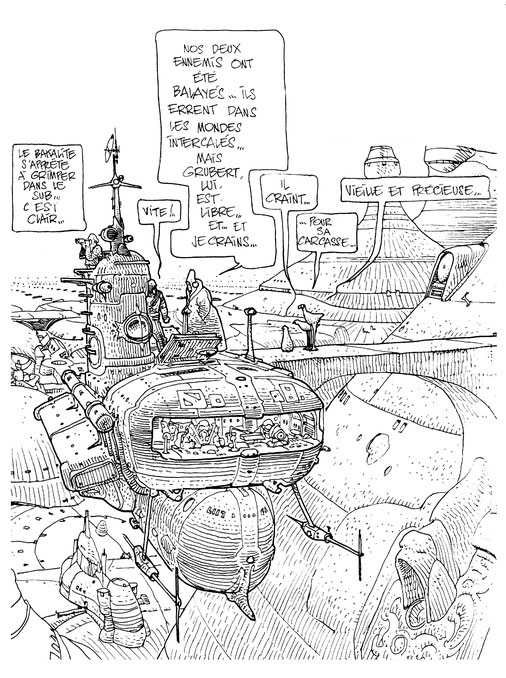

So it’s the Fleurs de Mal, or something opiate out of Oz, or seductive out of Clark Ashton Smith, or it's one of the uncountable pulp gardens or fields whose flowers are hungry, or induce narcosis, or both, or worse. And here our poor heroes are abandoned, for the next panel shows me the Bakalite,

waiting for the sub ...

Not just a sub, but the sub. I’ve been pitched, let me not forget, into the midst of a continuity. My first thought was that it might be a yellow submarine. Certainly it’s not waterbound, so perhaps it earns its name as some sort of sub-space or sub-orbital flyer.

In my copy of the English translation (Titan, 1990) page 10 lacks a title.

A lapse? An oversight in the printing? As it turns out, the title—“Grubert en pleine forme”—is not the only thing missing.

I take the missing title to suggest that on this page we see Grubert in his element, for what he is—which is to say, in his true colors.

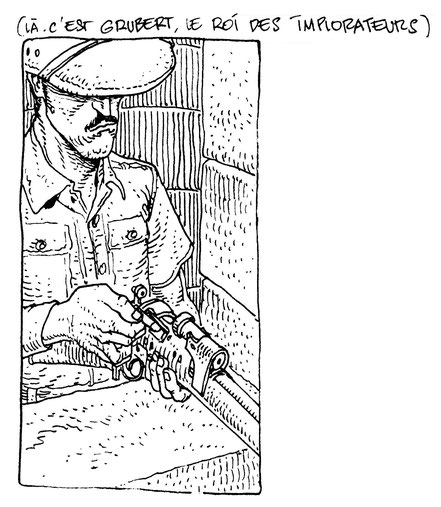

But, in addition, in the original, I find that above the first panel, between parentheses, the text reads, “Là. C’est Grubert, le roi des implorateurs”: “There. It’s Grubert, king of...”

But here my very uncertain grasp of the French language halts me. Is Grubert “king of implorers”? Is “implorer” simply a whimsical inversion of “explorer”? Or is there something I’m missing? (I concede, it doesn’t trouble me overmuch, right at this moment.)

Anyway, in the small first panel Grubert is loading a bullet into his rifle. In the second, the sub floats toward the landing stage on which the Bakalite stands. In the third—another small panel, horizontal, this time—Grubert raises his rifle (we never see his eyes) and thinks,

“Mœbius sure likes to make trouble!”

What is he talking about? Obviously he knows he’s in a comic strip, but is he commenting on the plot? Or on the artist’s freewheeling and mischievous improvisation of the story? Or on the little blobs and dots of ink that appear to be tormenting his rifle—eating it, perhaps? Literally, the French tells me “Mœbius is a lover of scandal”, and perhaps this makes more sense: “Mœbius”, for Giraud, was a means of breaking new ground, of pushing against the limits of what was expected of him, and if he surprised or unsettled his audience, this was some part of his intention. Anyway, this is our last glimpse of Grubert in this story, so make the most of it.

The next panel is a handsome composition showing the Bakalite boarding the sub—

“Hurry!”

says the man emerging from the turret—and, troublemaker or not, Mœbius does some tying up of the plot:

“Our two enemies...”

Houm and Boaz. Not merely degenerate humanoids, or junctor thieves, but “enemies”. As I suspected, there is a political dimension to the maneuverings in this story. Or is the old Bakalite just a paranoid self-dramatist?

“... have been swept away. They are now lost within the interpolated worlds.”

Any plurality of “worlds” invites me to marvel. To offer a subset of this plurality is to conjure us deeper into realms of fantasy. The interpolated worlds. A marvelous phrase. Interpolated. (In the French, “intercalés”.)

Where are they? Between the panels?

“But Grubert is still at large...”

“libre” – free, at liberty. And still taking liberties. We know that.

“... and I fear--”

“I fear” sounds like the Bakalite might be stating his concern about a negative outcome of this narrative conjunction—our enemies are swept away, but Grubert remains remains at liberty. His birdlike companions give it a more corporeal complexion:

“He fears--” “for his old--” “--and precious carcass!”

That’s the bottom line. But on that note I am suspended—there is suspense, as the story rushes to a climax—because as I pass to page 11,

THE WHITE FOREST

my attention is transferred back to Houm—“Hurry!” he says—and Boaz, running across the first of three horizontal panels, along a straight path between some peculiar stalagmite-like (fungal?) growths, behind some of which crouch armed men.

To have come so far, and yet to find myself back where I started—an ambush. In the next panel they are surrounded and Boaz concludes (not for the first time),

“We’re doomed!”

He puts up a fight in the third panel (though the figure striking out at his crowding attackers has a nose) while the narration takes a more distanced view:

Do not be mistaken ...

I am told—just in case I’ve jumped to any wrong conclusions...

Boaz is a master.

A master of fisticuffs, a warrior, it might appear. But is it that I might be mistaken about?

His ways may seem a little strange to us...

The narrative voice adopts the ironic distance I may have neglected as I got caught up in the suspense and the action. Am I mistaken because I suppose what I’m seeing is merely one of my daydreams—a fantasy of struggle and triumph against the odds?

... but that’s because he lives on a slightly aberrant world...

That ought to give me pause. Slightly aberrant. Not aberrant in a major way. Only slightly. Is that why I recognized it, became accustomed to it so quickly? Are the worlds of fantasy only slightly aberrant, but founded inextricably on the world we know, and unavoidably shaped by its values? Are the aberrations of Boaz’s world no more than a distorted reflection of my own cultural presumptions?

In any event, the fighting lasts for a reasonable amount of time ...

... but is represented by just this panel. The “reasonable amount of time” is presumably the time it takes to read the commentary plus whatever time I care to imagine—or interpolate. For in the next panel, on page 12,

PURIFICATION THROUGH FIRE

there has been an another lapse of time:

And after three days and three nights of various festivities ...

Houm and Jakin have been stripped and chained to separate posts, in a woodpile, wearing absurd caps. Behind them, along the rear of the panel, are the heads and shoulders of a row of rather chubby men wearing what appear to be bakers’ caps; in the foreground a procession of singers wearing headgear similar to that common in the world of the Arzach stories. Houm says,

“These songs are truly bizarre ...”

and Boaz lets him know the bad news:

“These are magical songs that have the power to raise the temperature of wood to the point of ignition, Houm. We’ll very likely burn to death.”

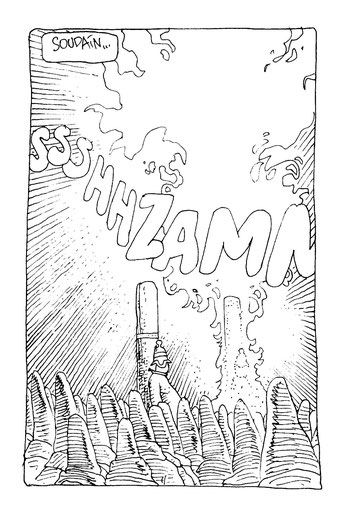

“[C]ertainement” in the original. But before I even have time to begin worrying about our heroes’ latest predicament,

No Billy Batson, no big red cheese. Boaz ignites, and

At the same time ...

(in some other world) in the third panel,

“Shiiit!” “The Bakalite!” “Shot by Grubert!”

Shot right through the ear muffs. He looks mildly discomfited, dimly surprised.

So! It’s not Boaz in this story who’s the assassin, but Grubert. The Major.

The last page, baldly titled

LAST PAGE

returns me to the outskirts of Bolzedura, where Houm is sitting in the grass rubbing his head. He’s somewhat confused, but—

“Boaz ... Poor Boaz...”

—he remembers what happened and realises soon enough that things didn’t work out:

“It’s all over ...”

Smoke drifts across the panel from somewhere in the city, while something—which turns out in the next panel to be a piece of shattered machinery—is shrieking.

Oh. Is that all that’s left of Boaz? Presumably they were snapped back to their accustomed world by the death of the Bakalite. Too late for poor Boaz.

As Houm saddles his “horse”, he sees Grubert’s spaceship taking off, but the final tier—a three-panel epilogue or coda—pushes all I’ve just read quickly into the past:

And on the following Jan.127th...

Another nostalgic holdover from Terran antiquity? But are the years on this big planet so long that in order to have only twelve named months they must be swollen and stuffed with an excess of days? How long, then, has passed? A reasonable or an unreasonable amount of time...

More prosaically, might I suppose this is simply Giraud’s fancy way of letting me know he’s referring to May 7th (31 + 28 + 31 + 30 + 7)? That just happens to be the day before his birthday.

Why the day before? Does it signify that “Le Major Fatal” marks the end of a period of gestation, heralding the full term and new birth of the artist known as Mœbius? One might reinforce this argument by pointing out that fifteen years later, when Giraud redrew the first episode of Le Garage Hermètique de Jerry Cornelius (which originally began in the same issue of Metal Hurlant) he dated the beginning of that celebrated and fondly remembered series to precisely May 8th.

Another, more prosaic explanation is possible. While in three out of four years January 127th would translate to May 7th, the year in which “Le Major Fatal” was published was a leap year. The 127th day of 1976 was therefore Thursday May 6th. Is it possible Giraud intended to indicate his birthday, but, at the end of a marathon session of drawing, simply miscalculated—subtracting a day for the leap year rather than adding it?

Anyway, a figure stands in a large room, gazing from a large, arched window, over the sea and toward the sunset. He says,

“All this is ancient history now ...”

Yes, the adventure’s over, sealed in the past. The fortress (?) from which the figure gazes is set atop a sheer-sided pinnacle of rock, set in the sea.

“Grubert took off to deep space with the junctor ...”

Degenerate humanoid. Junctor thief.

(On the contents page, the story was listed as “Gruber’s Jonction”.)

“May the rats eat him!”

Meddler. Assassin.

Of course, had I been following the adventure from Grubert’s point-of-view, possibly I might have had more sympathy for his action. The Bakalite... did he not perhaps deserve to be shot?

And yet, here I feel my age. I’m of a generation that could still be shocked by political assassination, and cannot be reconciled to believing political realism involves accepting the naked exercise of power on behalf of self-interest.

Or maybe it’s not my age. Maybe it’s just a matter of temperament.

“What was meant to happen did happen ... !”

It may be worth comparing the story narrated by Giraud’s wife, Claudine, on page 5 of an earlier Mœbius strip, “the Detour” (“La Deviation”), first published in 1973:

What you’d expect to happen happens: we succumb to their numbers. They bind us tightly and carry us through a maze of tunnels and dark caves, to a huge cavern deep inside the mountain... Soon we hear the echoing sound of barbaric blood-thirsty melodies... My blood freezes in my veins, for I recognize the songs which traditionally precede the tourist sacrifices... We are doomed!

Later, in the 5th episode of The Airtight Garage, Grubert may be seen to think, “So, this it ...! What’s happening now was eventually bound to happen!”

Major le fataliste, indeed. Que sera sera.

Or, to be more precise, “Ce qui arrive devait arriver!”

“Bah!”

Doesn’t mean we have to be happy about it. (And I shall discover, in due course, that this was not Grubert’s original thought, back in 1976, but a rewrite—was I fated to make this discovery?—dating from 1979, and the first publication of Le Garage in book form.)

The individual who says “Bah!”, by the way—a figure looking out over the sea, and looking back at what happened and cannot now be helped—is apparently Houm Jakin, out of his cowboy duds, high-collared, immaculately curried and holding a monocle in a small claw-like hand that recalls the hand of the Bakalite.

Need I infer from this latter detail that some mysterious transmigration plays a part in the plot? I think not. But let me concede that, on Houm turf, Jakin looks thoroughly decadent, and none too appealing. If the claw-like hand is not simply an impromptu slip (like Boaz’ nose on page 11) let me read it as a sign that, however I may have been prepared to accept him as a buddy back on the trail, he may be, in this slightly aberrant world, no better than the Bakalite.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

I think the foregoing is not simply an expression of nostalgia. There’s an element of that, to be sure, but I’m also discovering what I probably knew already—or ought to have known: that, to put it kindly, my experience is historical. To put it less kindly, I’m a fossil, a relic. In some ways what I’m looking at looks both familiar and very fresh; but it’s evident that it belongs to a different time, and a very different world. Leafing through a copy of Metal Hurlant the other day, I came across an article on the prospect of the use of videotape in the home. For the first time it was conceivable that people might be able to maintain a library of film, taking one off the shelf and viewing it—or referring to it—whenever they wished. There were no personal computers. No mobile phones. The original Star Wars had come out just the year before.

I may rely on my experience of those somehow bright but distant days to animate and inform my reading, but, while some pages from The Airtight Garage recall to me with an almost tactile immediacy the rack from which I picked the magazine in which it appeared, “Major Fatal” has no time or place in my memory, except as a dim and misplaced pendant to my curiosity, then fresh, about the work of Mœbius. Reading this story, I am not transported back to the moment of its initial discovery, or a precedent experience of pleasure. Yet back I have certainly gone, within myself, to a time now lost. Not to what was, but to what might have been. This was a story I did not read or could not read, and it vanished from my horizon. Suddenly it’s here in front of me, bright and alive.

Not Jean Giraud, alas, who, in the time I was sleeping, continued producing a prodigious body of work—some of it marvelous—and aged, and died. This is the nature of our time in this world: it passes. So it goes. But artists lay down sections of a parallel time that intersects with the lifetimes around them. It would be a waste for me to regret that we slipped past one another at a time when the best I might have offered him was a fan letter—though artists are always in need of, and often grateful for those who read, who look, who listen; and particularly for those few who, as in the Henry James story, might care to apprehend “the figure in the carpet”. Anyway, it pleases me now to be writing these words in recognition of a connection made, across time, with an artist who, in “Major Fatal”, was just discovering the way to one of his most characteristic works.

I’m finding my way to that, too. But the beginning is this, the moment of “Major Fatal”, which delights me now (or, to be more accurate, delighted me in a “now” already receding) and prevents my engagement with the work of Giraud/Mœbius from being merely retrospective and historical. Works of art, of course, have a history; but, if they are to exist at all, they must continue to exist in the present—the present of an encounter not circumscribed by prior judgements.

I insist—as any self-respecting reader ought to insist—on the opportunity of making discoveries...