Too much room to go astray

an innocent attempt to follow the bewildering thread of Tueur de Monde

If it seems strange to us that the writers of these stories should have used such a trivial literary device as punning so extensively, it should be remembered that they were heirs to a very long tradition of this kind of word-spinning. The Old Testament is full of it...

John M. Allegro, The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross p.48

Tueur de Monde was my first experiment in reading Mœbius in French. “World Killer” is, I think, the obvious rendering of its rather ominous title, but there was an English translation in Heavy Metal, in the early eighties, under the less ominous title of “The Twinkle in Fildegar’s Eye”. Rather a clever title, playing on panels 35 and 42, but it suggests a quality of mischief somewhat at odds with the tone of the story, which is gentle and melancholy.

I didn’t see the story at that time, and when I became curious, recently, to read it, I considered getting hold of the issue of Heavy Metal in which it appeared (vol.7 #1, April 1983). But the original presentation in French was as a short book, with one panel per page, whereas the version in English made an attempt to arrange the panels on typical magazine pages, seven of them—a format for which they were not designed.

Also, the English version was in black and white. So was the original French edition (Humanoïdes Associés, 1979)—or blue and white, to be more precise—but I’d seen panels reproduced in color. So I settled for the second edition (Casterman, 1988).

It’s rather beautiful. The images are presented with plenty of white space around them, and, while most of the dialogue is given in balloons, the panels are supported by a text printed below. It looks and feels very much like a children’s book. The cartooning is both light and careful (with mannerisms that, in places, recall Hergé) and I’m charmed by it. But, simple as it is, the children for whom this story is intended are strange indeed.

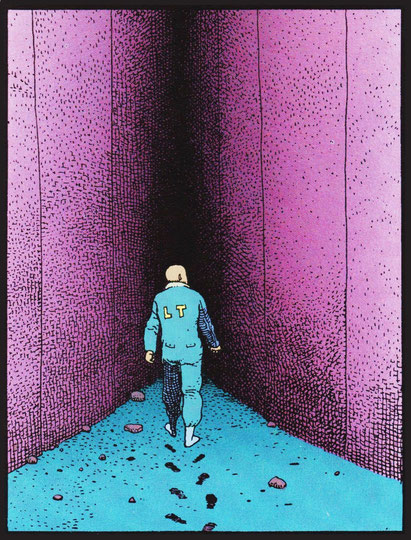

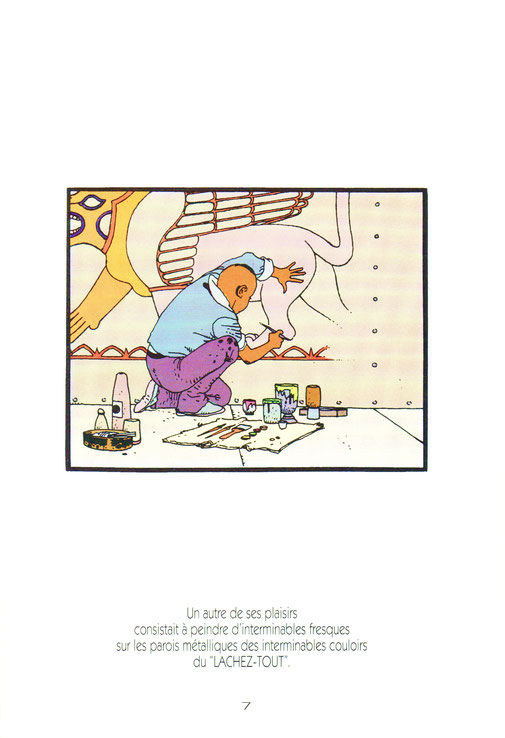

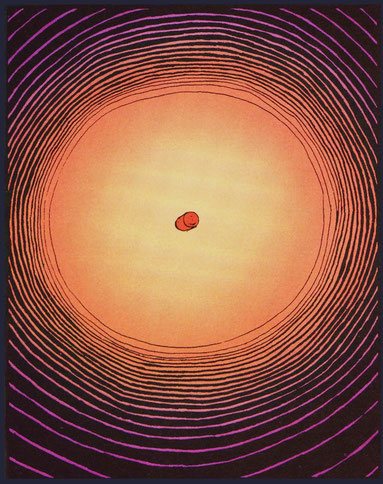

I suppose it might be read quickly, but the format allows a leisurely, lingering attention—just as well, considering my uncertain grasp of the French language. Nor does the narrative encourage haste: the first seven panels introduce us to what our protagonist, Fildegar, does on his spaceship as he travels between galaxies at a million times the speed of light. Fast as this may sound, he’s in a void, a vast emptiness, with time on his hands. He likes nothing better than to spend time among the flowers in the hydroponic garden (panels 1 & 2)—a detail that recalls Douglas Trumbull’s Silent Running. He also paints murals on the walls of the spaceship’s “endless” corridors (panel 3) and sits for long hours “contemplating the crystal that palpitates at the heart of the vessel” (panel 4). Two panels (5 & 6) show him sorting carefully through old photographs.

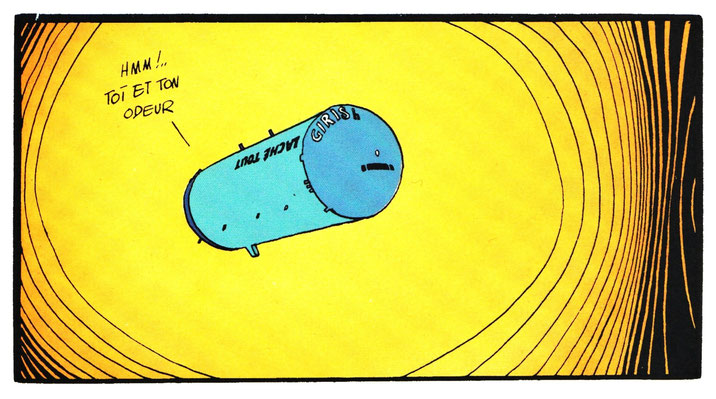

But sometimes he’s simply bored (panel 7); and the narrative movement from his appreciation of life’s pleasures, and artistic activity, through periods of meditation and reflection, to a state of ennui establishes the melancholy tone. Fildegar is alone, isolated—his ship, in panel 2, is rather a rude canister, suggesting enclosure—distant from all manner of urgency or social involvement. It appears that the name of the ship (“LACHÉ TOUT” in panel 2, but subsequently, in the text, “LACHEZ-TOUT”) may bear the implication of “Let It All Go”—in the sense of a renunciation or leavetaking—or possibly “Leave It All Behind”. In the first English translation, it was given as “Drop Everything”. (Another reading will be suggested below.)

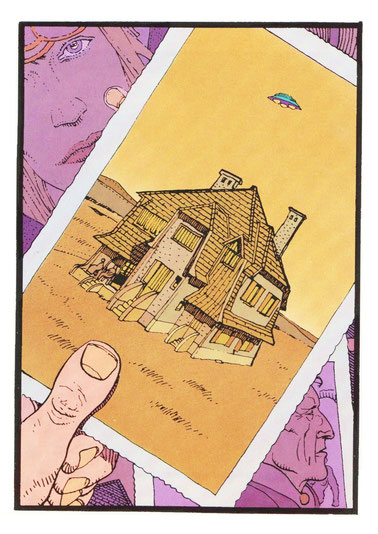

The fact that one of Fildegar’s photographs is a panel from the fifth episode of Le Garage Hermétique, showing the face of Jerry Cornelius, may be no more than an in-joke; but, published in 1979, the year Giraud brought that particular creative adventure to a close, it might also be seen as a recognition by the artist that one phase of his life was coming to an end. This reading, informed by hindsight, need not be considered fanciful: it is amply documented that Giraud invested himself emotionally in his stories, and that for their substance he sought the guidance of his subconscious mind.

Fildegar too is an artist—we see it in panel 3, and he will subsequently be identified as such in panel 33—but an artist evidently less concerned with producing work for an audience than with seeking to fulfil his own needs.

Back in the sixties and early seventies, Giraud had felt this private impulse toward artistic fulfilment while working on Blueberry for Pilote: “I was presentable,” he said in an interview for Hasko Baumann’s documentary, Mœbius Redux: a Life in Pictures (2007), “and got to the meetings... on time. But in the depths of myself I was in turmoil. I felt different.” At the end of the seventies, however, having opened the doors to creativity in ways that had secured his position as a major figure in comics, he was primarily concerned with changing his spiritual orientation.

The panel in which Fildegar’s ship at last re-emerges into “human space” (panel 8) is one of the simplest. Text rather than image does the work, and one thing the text implies is that Fildegar is not entirely in control of his journey. If he’s a wanderer or an explorer, nevertheless it’s the crystal at the heart of the ship that judges this nearby planet interesting. Later, he’ll say that he travels the universe at random (panel 32). The crystal is shown only once, and its assistance is articulated only in passing; but Fildegar’s reliance on it is subsequently made clear in panels 38 and 39.

In 1978, as Le Garage Hermétique entered its final phase, it turned out that what Major Grubert was carrying in his suitcase was a fourteen-faceted crystal—essential to the process of personal transformation he would undergo in preparation for his journey to the first level. In 1983, a giant crystal would be found at the heart of the blue pyramid in Upon a Star, waiting to power its journey to Edena, the legendary paradise planet. At the end of 1983, in “Celestial Venice”, Mana carries a “soul crystal” in a case of blue gold, in order to bring about the regeneration—indeed, the “crystallization”—and elevation of a ruined and deserted city. Many other images incorporating crystals would follow. In an interview with Kim Thompson of The Comics Journal (December 1987), there occurred the following exchange:

Giraud: ... Very often I used to compensate for quality with quantity on my drawings... If there is a simplification, a synthesizing, a purification in my work, it’s not because of a conscious decision, although it’s part of a set of rules that all my teachers have tried to teach me, which is that... beauty goes with simplicity, and simplicity goes with precision.

Thompson: The image of the crystal seems very important to you. Is this part of this search for purity and simplicity?

Giraud: Yes, but here we’re entering an area different from style, namely theme...

As late as 2008, in Arzak l’arpenteur, the last Werg necromancer, Ark-le-seul—guardian of the memory, the soul, and the conscience of his race—would sit, “cloistered in a palpitating crystal”.

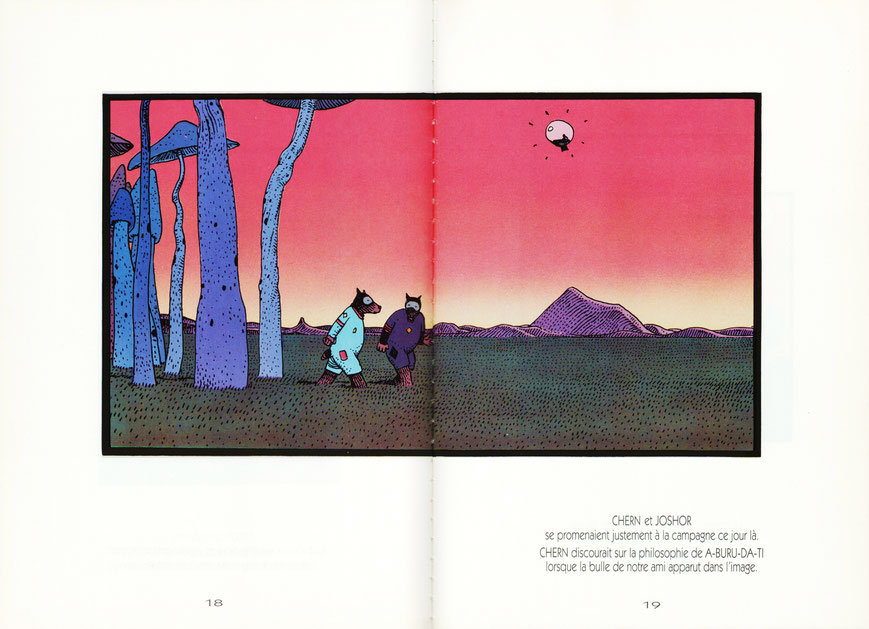

If the network of energy surrounding the planet Fildegar finds is simply sketched in panel 8, the following panel (though pictorially modest) does a little more to substantiate the text’s insistence that the spectacle is impressive. The focus of the panel, however, is on two inhabitants of the planet—perhaps the only two—who are watching the spectacle. They’re seated, we see them from behind. One has an arm around the other. They’re both plump, stocky. Fildegar will be described in panel 25 as a “young man”, but, to be more precise, he looks like a teenager (possibly not much older than Tintin). His face is simply drawn, unlined, indeed babyish—and the suit he wears in the latter part of the story is not unlike a set of baby’s rompers. By contrast, at first sight, it would seem reasonable to read the inhabitants of the planet as a couple, probably past middle age—an impression possibly reinforced by their apparent sexlessness when, in panel 10, we see them more clearly as humanoid creatures with animal heads. Dogs? (Or goats? They are referred to as “Tragos”, from the Greek.) Anyway, they are, we are told, “mild and contemplative”—just the kind of reassuring adults (grandparents?) that might appear in a book for the smallest children.

Panels 11-13 have a more conventional science-fiction look, as Fildegar exits the LACHEZ-TOUT in his bubble. The melancholy tone is further reinforced as he drifts past a ruined space station “dating from the war of the stars”. This placid, peaceful story has behind it other times—times of strife and upheaval—reflecting perhaps the influence of the cultural upheavals of the nineteen-sixties on Giraud’s development. At the same time, the “war of the stars” is also a reference to Star Wars, and to the moment when science-fiction and fantasy quit loitering on the margins of popular consciousness, and suddenly emerged at the forefront. Giraud, involved with the launching of Metal Hurlant, with Alexandro Jodorowsky’s attempt to make a movie of Dune, and subsequently with input into the designs for Alien, was plugged directly into this emergence.

Panel 14 (the only panel spread over two pages) returns us to the surface of the planet, where the two inhabitants are walking in the country “when our friend’s bubble appear[s] in the picture.”

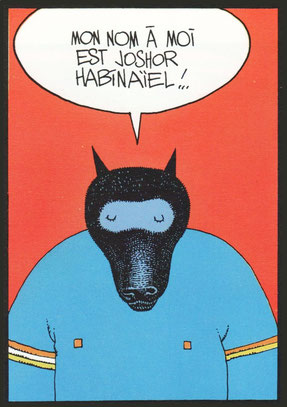

Is this a children’s story? At no point does it look more like a children’s book than here and in the next two panels. But, as Fildegar’s bubble appears in the sky, Chern is “discours[ing] on the philosophy of A-BURU-DA-TI”. And when the space voyager and the planet’s inhabitants introduce themselves to one another (panel 15) they speak “a galactic hebrew”. Add to this the fact that the planet is called Bar-Jona and one might come to the conclusion that behind the text is something more recondite than the simple visuals suggest. Indeed, the surname Joshor gives himself (Habinaïel) may acknowledge this union of disjunctive textual and visual elements if read (by way of word-play in French) as meaning “cunning/simplicity of God” (Habi[le]-naï[f]-el).

The three characters sit down together in the soft grass (panel 17) to watch an electrical storm, and thereafter Chern and Joshor are seen no more. They are older, they are settled, they are at peace. They are at home. In all these things they appear to present a contrast to Fildegar. But our business is with this young voyager, not with them.

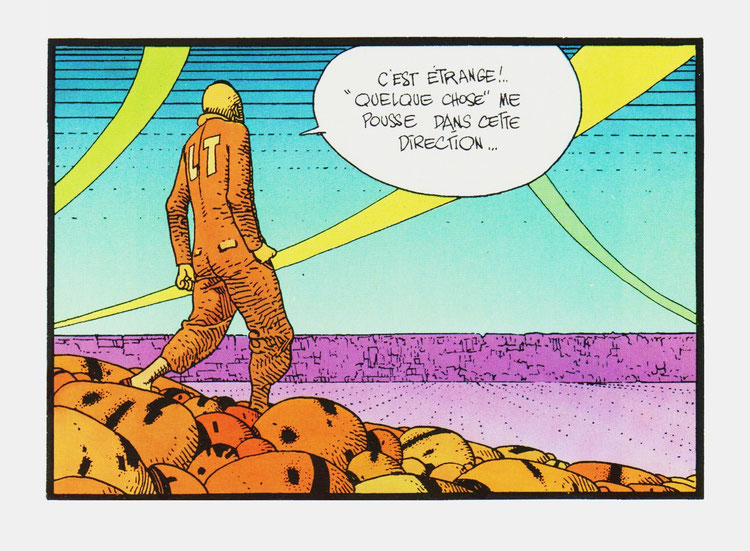

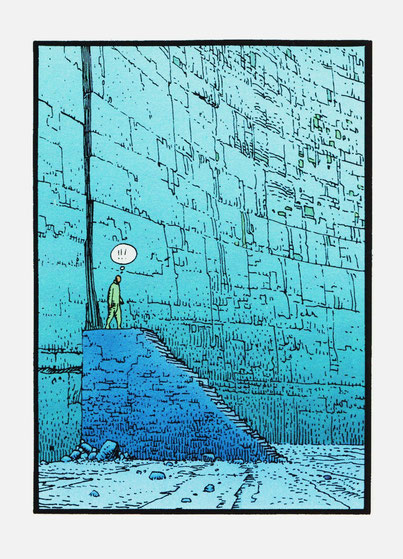

The next image is more sophisticated both in composition and in texture. Fildegar moves with some appearance of resistance—some stiffness about the shoulders—toward a remote cliff that extends from one edge of the panel to the other: “It’s strange!.. ‘Something’ is pushing me in this direction ...”

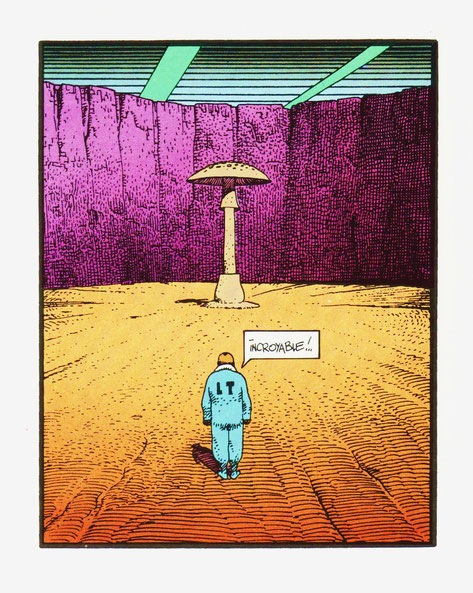

Panels 19-22 follow him into and through a crack in this enormous wall; they are simply composed, strong, carefully shaded, and compelling. Fildegar’s exit, on the other side of the wall, displays Giraud’s mastery of scale (23); his entry, down a set of ancient steps, into a space we have not yet seen, is stately (24); and he stands at the foot of the steps, folding his arms (25). Only then (26) do we see what he sees.

In the third “Arzak” story, the protagonist entered what looked like an ancient monument, descended some steps, and arrived in a large circular space—larger, indeed, than might have seemed possible from outside and above. Fildegar here also descends some steps; again the space is circular, and very large; but this space has only one feature—a giant mushroom. Fildegar approaches (panel 27) and the mushroom speaks (28). What it says is, literally, “I am Kurbalaganta and I’ve been waiting for you since the night of time”—i.e., “since before the dawn of time”. Fildegar falls over in surprise, and I laughed out loud; but here we have arrived at the esoteric heart of the story, because Fildegar, still seated on the ground, immediately translates:

KURBALAGANTA : KUR – BA (LA) G – ANTA!. BUT ... iT’S SUMERiAN ... AND ... WAiT!.. THE EXACT MEANiNG iS: <<CONE OF THE ERECT PHALLUS!>> ...

(panel 29)

There follows, over the next six panels (30-35), a curious conversation and a mysterious sequence of action. Giraud re-establishes a sense of scale (panel 30) by setting Fildegar and the mushroom in the distance. Beyond them is part of the circular wall by which they are surrounded. “You think you know many things, but you ignore the essential ...” the mushroom tells him. “For example, do you know that you are here to destroy me, as well as this planet!.?”

As the exchange progresses, Giraud brings the reader closer. Fildegar pleads innocence and, surely, considering his youth and his simple, open face, we are prepared to believe him. Yet, as he gets to his feet (31-32) he is seized by a strange impulse (33). Just as he is declaring himself “An artist!.. Always on the lookout for new sensations”—a phrase Giraud would acknowledge (Sadoul, Docteur Mœbius et Mister Gir, p.192) as a slogan accurately describing himself—he approaches the mushroom with raised hands. He breaks off a piece of the cup at its base (34) and eats it (35). “Truly,” says the mushroom, “you know not what you do”.

FILDEGAR understood his error, but too late... A dull rumbling beat in the depth of his skull.

(panel 36)

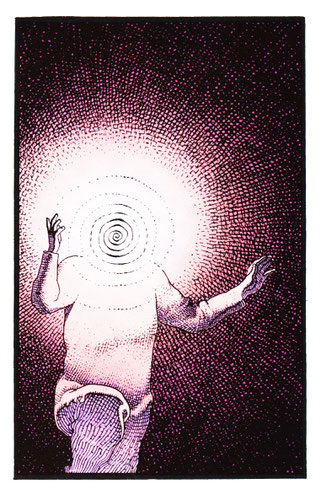

He leaves the way he came, holding his ears (panel 37), then calls to his crystal for assistance (38). But the ship is gone (39) and a transformation begins (40). This is “the final end of the era of the sacred mushroom” (42).

It’s undeniably slim, but I enjoyed the experience of reading the story—enjoyed it with my eyes, panel by panel. (Giraud released the colored artwork first of all as a portfolio.) I enjoyed its curious changes of register, of tone, its modest surprises, its enigmatic journey. I’ll admit, however, that I found the ending both abrupt and opaque. Yet if I didn’t respond wholeheartedly, why complain? I enjoyed my time in its company and, moreover, my uncertainty concerning the end offers a pretext to return to it, to look again, more closely.

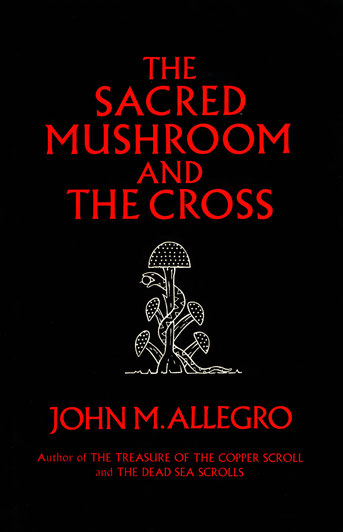

The mushroom is no great puzzle. The text accompanying panel 27 identifies it as “Une amanite tue-mouche géante.” Even with my rickety French (and even if the coloring fails to give it its striking red top) I was fairly sure this was a giant amanita muscaria, the subject of a once controversial book by John M. Allegro, The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (1970). This is confirmed by Giraud’s response in an interview with Numa Sadoul:

I’d begun, as sometimes happens, a series of drawings that were going nowhere. And then there was grafted on to it the story of the mushroom, because I was reading a book that got me excited: The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, a study by philologist John Allegro on the connection between psychotropic plants, notably the amanita muscaria, and the genesis of religions in the mediterranean basin. An interesting subject, and one totally hidden in the official histories of religion. My story is made up of bits and pieces on this theme. It was at this time that I’d stopped smoking cannabis.

You made a little parable on the elimination of hallucinogenic substances?

That, and all such crutches. And not only on a personal level but also on a cosmic level. The human race sends a killer to the giant mushroom which is the source, the great spirit.

The killer doesn’t know he’s a killer: “You don’t know what you’re doing”...

Yes, it’s full of ambiguities.

(Sadoul, Docteur Mœbius et Mister Gir, p.191)

John Marco Allegro was one of a team of scholars assigned to translate the Dead Sea Scrolls, but his independent views brought him into conflict with colleagues and critics. The publication of The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross in 1970 brought him a measure of notoriety, but definitively put an end to his reputation as a serious scholar.

Fildegar’s translation of the name Kurbalaganta (panel 29) is found on page 50 of Allegro’s book. Approaching the mushroom, in panel 27, Fildegar’s remark (“C’est une véritable merveille de l’univers”) echoes the remark of Pliny, as reported by Allegro: “To Pliny the fungus had to be reckoned as one of the ‘greatest of the marvels of nature’...” (Allegro, p.54). Even the seemingly innocent adjective applied to the mushroom (“géante”) supports a reference in Allegro’s book: “our own word ‘giant’ comes from a similar Sumerian designation, found in Greek form as the name of the mushroom” (p.132). One might wonder whether Fildegar’s name also carries a playful echo of the mushroom’s name in English: Fly-Agaric → Fl – egar. But the name might be pulled apart in more ways than one.

The name of the planet on which Fildegar lands (Bar-Jona) may be traced to Allegro’s discussion of

[t]he well-known word-play in Matt 16:18: “you are Peter (Petros), and upon this rock (petra) I shall build my church . . .”

—Allegro’s point being that “Peter’s name is an obvious play on the Semitic pitrā, ‘mushroom’, and... his patronymic, Bar-jonah, is really a fungus name...” (p.47). In addition, behind “Bar-Jonah” (“son of Jonah”) Allegro finds the Sumerian BAR-IA-U-NA, translated as “capsule of fecundity; womb” (p.38). The subject on which Chern is discoursing when Fildegar’s life-pod appears in the sky is the philosophy of “A-BURU-DA-TI”—a word Allegro translates as “organ of fertility”, “womb” (p.96). So the planet Fildegar visits is not only identified with the mushroom, but with fertility, gestation.

And what will come forth from this womb? Among the possible meanings of GAR (Sumerian “place”) Allegro offers “womb/container” (p.224), so Giraud’s Fil-de-GAR may also derive from a play on the translation of Bar-Jona: Fil for “fils”, therefore “fils-de-GAR” = “son of womb”. Fildegar has come here to be born—or, more properly, re-born.

His fore-name (Osborn, which he gives when introducing himself to Chern and Joshor) may involve more wordplay. In French, “Os” = “bone” while “born” (as in “borner”, “borne”, “borné”) suggests limit, boundary or confinement. How we interpret this may depend on the level to which we suppose it belongs. On the one hand, Giraud may have merely found the name attractive or amusing: in Le Garage, the Osborn scale is a comparative measure of gravity—which is perhaps to say a measure of whether something is more or less playful. Playfulness does not exclude seriousness: an allusion to death or ossification and imprisonment might be read as suggesting that Giraud’s creative development as Mœbius—which, in Mœbius Redux (Baumann, 2007), he described as an “ejaculation”—had reached its limit. But it may be safer simply to take as the key another passage from The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross, also referring to death and imprisonment. Allegro quotes the words of Eleazar, leader of the Zealots (another uprising of the cult of the sacred mushroom, he argues) as reported by Josephus:

For from of old, from the first dawn of intelligence, we have been continually taught by those precepts, ancestral and divine... that life, not death, is man’s misfortune. For it is death which gives liberty to the soul and permits it to depart to its own pure abode... But so long as it is imprisoned in a mortal body and tainted with all its miseries, it is, in sober truth, dead, for association with what is mortal ill befits that which is divine.

(The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross p.181)

In story notes written for the 1987 reprinting of his works in English, Giraud was willing to consider death and transformation an equivalent outcome for his characters:

As I changed, going more towards a lifestyle more oriented towards health, meditation, and spiritual concerns, I began to notice that the endings of my stories changed too.

They went from showing the often violent death of the characters to showing a physical or spiritual transformation. Of course, in the end, it is the same thing, except that a transformation is seen from a different, more spiritual plane... In my more recent stories, a lot of my characters seem to either fly away, or turn into light! I try not to be that systematic, but it is the way things seem to work.

(story notes to “It’s A Small Universe”, MŒBIUS 4)

The apparent destruction of Fildegar and Bar-Jona need not, then, be read as misfortune, so much as the symbol of a necessary liberation. If we look again at the name of Fildegar’s vessel (“LACHEZ-TOUT”), we find that “Lacher” is “to let loose; to release; to loosen”, so behind an immediate reading as “Leave it all” or “Let it all go” is perhaps a broader and stronger impulse toward total liberation. Allegro writes that the statement,

“I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matt 16:19) has its basis in an important Sumerian mushroom name MASh-BA(LA)G-ANTA-TAB-BA-RI read as “thou art the permitter (releaser) of the kingdom” by a play on three or four Aramaic words spun out of the Sumerian title.

(The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross p.47)

In Allegro’s notes, (ibid. p.235) this play on words is glossed as “remit, pardon; release” and “thou”, so behind the surface of “LACHEZ-TOUT”, however translated, is the promise that “you are released”.

The chapter in which this passage occurs is the one that begins unlocking the punning and word-play surrounding the sacred mushroom. It is titled “The Key of the Kingdom”. For a reference to the “kingdom of heaven” in Giraud’s story, see panel 36, where the mushroom declares that “Mon royaume s’etendait jusqu’aux ultimes galaxies”.

To the worshipper of the sacred fungus, the deity was present in the mushroom and offered his servants the “key” to a new and wonderful mystic experience. It was this “re-birth”, as it was called, that cleared away the debts of the past and gave promise of a future free from the cultic “sin” that destroyed the initiate’s free communion with God.

(The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross pp.47-8)

The mushroom tells Fildegar that he has come as a destroyer. Fildegar protests his innocence by saying he wouldn’t hurt a fly. Since the mushroom is “tue-mouche”—“fly-killer”—this signals not only Fildegar’s lack of understanding, but a failure to recognize himself in the mushroom god. Innocent insofar as he is uninitiated, he does not yet understand that he has been brought here to be initiated. Union with the god involves renunciation of self—“destruction” of the world constructed by the self. Liberation from the debts of the past appears to be why Fildegar came to this place of rebirth.

When Giraud’s friend and sometime collaborator, Alexandro Jodorowsky, had articulated these issues in his film, The Holy Mountain (1973), he told his band of seekers after immortality,

We shall destroy the self-image—unsteady, wavering, bewildered, full of desire, destructive, confused. When the self-concept thinks, “This is I,” and “This is mine,” he binds himself, and he forgets the Great Self...

Subsequently, he told one of them,

Fool! Destroy your illusions! Free yourself from the past!

And he guided them all through a ritual of death and rebirth in these terms:

Surrender yourself to death. Return what was loaned to you. Give up your pleasures, your pains... Surrender what you have, what you desire. You will know nothingness; it is the only reality... The grave is the door to your rebirth. Now you will surrender the faithful animal you once called your body... Now you are an empty heart, open to receive your true essence, your own perfection, your new body, which is the universe, the work of God. You will be born again...

*

To recognize a reference is not, of necessity, to understand the work in which it is detected. What puzzled me on first reading continues to leave me uncertain.

When Fildegar eats of the mushroom, the mushroom says, “Truly, you know not what you do” (panel 35). This not only echoes the words of Christ, as given in Luke 23, but is entirely in line with Allegro’s thesis that many tales in the Hebrew Bible, and the Ten Commandments, and all of original Christianity, were fictions devised to codify the elements of a fertility cult that used the sacred mushroom to induce visions of unity with its god, incarnated in the mushroom.

Fildegar’s reaction is ambivalent. He holds his head, he flees, tries to retreat to his ship, but the crystal—his guide—is gone. This, perhaps, is not so hard to understand: the renunciation of self, in an initiatory experience, may be attended by disorientation, even by terror.

On the other hand, the text tells me Fildegar “understands his error,” albeit too late. Is it an error only from the viewpoint of the innocent child who supposed he might ingest the mushroom as food—“It’s delicious!” he says—but now finds he cannot contain the experience of the god? Or did the error lie in the premise of Allegro’s book?—that the altered state of consciousness produced by eating the mushroom constituted the mystical experience encoded in the ancient texts. In The Holy Mountain, Jodorowsky had already mocked this notion, by having an obviously stoned champion of psychoactive drugs insist that

The cross was a mushroom. And the mushroom was also the tree of good and evil. The philosophical stone of the alchemists was LSD. The Book of the Dead is a trip; and the Apocalypse describes a mescalin experience...

Coming at the end of the sixties, Allegro’s book may have been taken by some as confirming the fundamental truth of the psychedelic sacraments then being widely explored. But, for all that he identified the drug experience with religious mysticism, Allegro was radical in his dismissal of both, and took a conservative view of the value of altered states of consciousness:

Above all, the sacred fungus... gave [its users] the delusion of a soul floating free over vast distances, separate from their bodies, as it still does to those foolish enough to seek out the experience.

(The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross p.151)

Reading Allegro’s book now, I find it hard to avoid the suspicion that, while it advances some intriguing and plausible observations, its argument is insufficiently rigorous, being in many places not only circular but fanciful. To put this briefly: having identified the possible roots of some translingual puns embedded in the language of the Bible, I’m not convinced Allegro didn’t substantiate his thesis by inferring further puns never intended, and drawing historical conclusions from them. (The identification of the amanita muscaria as the sacred mushroom, as originally advanced by R. Gordon Wasson, has also been questioned.)

But Giraud, who delighted in the word-play of Raymond Roussel, appears to have been sufficiently intrigued by Allegro’s thesis that he included a mushroom in-joke in the thirty-first chapter of Le Garage, when Graad says of the Major, after an altered state of consciousness has been achieved, “What a Flash! This Major is truly a son of thunder!” That mushrooms were traditionally supposed to appear in the wake of thunder storms is a detail insisted upon repeatedly in Allegro’s book. In addition, the little flecks that appear on Graad’s shoulders are not dandruff, but a visual echo of the remnants of the volva that remain visible on the cap of the amanita muscaria, when fully grown.

There’s a simpler way to account for Fildegar’s confused flight from the mushroom: Giraud was recalling an experience triggered by an experiment with hallucinogenic mushrooms that took place in Mexico in 1965. It lasted from six to eight hours, and, as he recalled in an interview for Hasko Baumann’s documentary, he was turned inside out, truly shaken, and wondered for a long time whether he would recover his integrity. He referred to the experience as a very violent or fierce initiation; but it became the foundation for an enduring curiosity about the mind’s limits, which in turn fed into his work as he sought to discover what might be brought forth from behind and below the architecture of everyday consciousness. The explosion that destroys Fildegar’s world at the end of Tueur de Monde is like a signature, coming at the end of the period 1973-1979—the period of the explosive emergence of “Mœbius” as a comic book artist—and identifying his point of origin.

And when he wrote in his memoir about “La Deviation”, about how his friends had challenged him to do the something different that he was always talking about, Giraud’s language echoed the experience of Osborn Fildergar that he’d pictured two decades earlier:

Do it! It was ringing in my ears as I made my way home. The drumming of the words broke my skull. The ancients must have felt something like this when they consulted the Delphic oracle. Do it! ... I hurried to buy a pen-holder and some paper and set to drawing La Déviation as if my life depended on it. This was the point of departure...

My friends said to me, “Do it” and I did it: I let Moebius speak. His unleashed pencil went by itself on the page, seized by the sacred inspiration of the Pythian oracle by whose prophetic word my friends had passed to me the sacred fire.

(Mœbius/Giraud, histoire de mon double pp.161, 166)

Let me, however, learn the lesson of caution from John Allegro’s too-certain decoding of a mystery. I can’t pretend to be sure what Tueur de Monde meant to Giraud in the economy of his creative life. It stands on the cusp of new beginnings, ahead of both a prolonged collaboration with Jodorowsky on the Incal, and his own work on the Edena cycle. Unless I’ve been led astray by a string of allusions (“fil” = thread, “égarer = to lead astray) and must be considered, as a consequence, a true fils d’égare (“son of bewilderment”), it would seem that rebirth is at the heart of the story; but while Giraud dramatizes the incomprehension and resistance of the unenlightened self, he finds no means, within the story, of evoking rebirth—offering in its stead only a symbol of its fulfilment.

A symbol that functions by producing a reflex of understanding is merely a code, a reference for those who already know what it means, rather than a living and active symbol whose context gives it life and meaning. Fildegar’s head may be awhirl, but neither my enchantment nor the narrative carry me as far as experiencing (if only by sympathy) his transformation; nor do they offer a decisive clue to its nature. The story delights me, but its conclusion does not produce in me the conviction that it is entirely successful. As a result, rather than being guided by the feeling produced by a fully realized aesthetic synthesis, I’ve attempted to understand the story by an intellectual effort—or, let me be honest, by diligent pedantry. It’s not quite enough.

None of the panels in Tueur de Monde bear the “Mœbius” signature. There is, however, in the second panel, on one end of Fildegar’s cylindrical vessel, the word “GIRISh”—containing, obviously, the “GIR” of Giraud.

Allegro offers several translations of the Sumerian GIRISh, one of which is “butterfly” (ibid. p.14). Giraud, in a 1974 interview conducted by Numa Sadoul (to which the artist supplied facetious answers and whimsical illustrations), alluded to “that famous brush stroke, known as ‘butterfly stroke,’ which has made me famous in this latter part of the 20th century” (“Moebius circa ’74”, page 5 panel 3). And, obviously, a butterfly is a creature re-born after a period of enclosure and metamorphosis. In Jodorowsky’s autobiographical film, Endless Poetry (2016), the director refers to old age, unsurprisingly, in terms that echo the renunciation of self ahead of re-birth:

Old age is not a humiliation. You detach yourself from everything. From sex, from wealth, from fame. You detach yourself from yourself. You turn into a butterfly, a radiant butterfly, a being of pure light!

But those of us who rely on translations ought always to be careful in our conclusions. In French, Giraud referred to CE FAMEUX COUP DE PiNCEAU DiT “À LA REBROUSSE-POiL”. The phrase in quotes refers to brushing a hat against the nap, and may have something to do with Giraud’s willingness to work against the grain, or his ability to rub people up the wrong way.

But no butterflies.

And the reader who’d prefer not to read anything into this simple piece of linguistic mischief is entitled to object that the Sumerian ideogram sometimes read as GIRISh may also represent DUBUR (“scrotum”), DUGGAN (“wallet”) or KALAM (“kidney”).