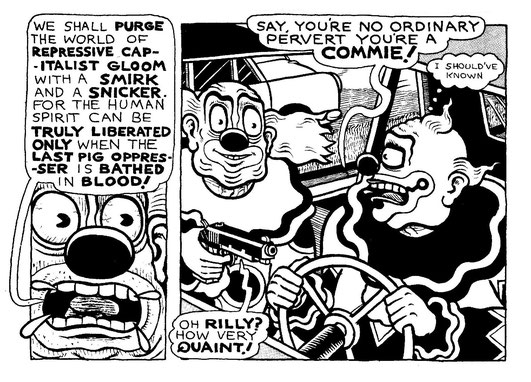

The NEXT THRILLING CHAPTER 13

– The revolt of the masses

This is the thirteenth part of The NEXT THRILLING CHAPTER—and unlucky for Doctor Benson, it would seem. On the other hand, after the recap, he’s got almost the whole chapter to himself.

One other thing in this one is an animated special effect I borrowed (unasked) from Kim Deitch. I’m sorry I didn’t do it justice—too much to do, too little time—but I wanted to acknowledge, in passing, the delight I’ve taken, over half a century, in his sometimes crazed comic strip stories.

The epigraph at the head of this chapter was lifted, for no very profound or compelling reason, from Ortega y Gasset’s The Revolt of the Masses (1930), a masterpiece of alarmed snobbery. Its complaint: look at all these people, and they don’t know their place.

Ortega is also resentful that “mass-man” is not more astonished and appreciative of the wonders of our modern civilization, and anatomises the “radical ingratitude” of this troglodyte to the physical sciences on which civilization depends. Paradoxically, he asserts that most scientists are also mediocrities who must be counted among the mass, because their estimate of their own mastery of a specialized subject situates them (like the mass) in their own self-satisfaction, so that they brook no argument, imagining themselves fully-formed in their own small, ready-made opinions.

Meanwhile, the quality of his own reasoning is often outweighed by his self-assurance:

I know well that many of my readers do not think as I do... [but] although my opinion turn out erroneous, there will always remain the fact that many of those dissentient readers have never given five minutes’ thought to this complex matter. How are they going to think as I do? But by believing that they have a right to an opinion on the matter without previous effort to work one out for themselves, they prove patently that they belong to that absurd type of human being which I have called the “rebel mass.”

And what type of human beings might they be if, on grounds that they had not given the matter five minutes’ thought, they were to accept the opinion (possibly erroneous) of Ortega y Gasset? A clue may be found in a footnote where he writes that, “Abasement, degradation is simply the manner of life of the man who has refused to be what it is his duty to be”.

If I am of the mass, is it therefore my duty to accept I am of the mass, and be docile while listening to Ortega?—but not to imagine I may thereby have gained an opinion. It is my duty, I suppose, to wait until I may be told what to do.

Okay, let’s acknowledge this nonsense has a historical background. Ortega was writing with an eye on the rise of Communism and Fascism. And what does he oppose against them? Liberalism—which is, it would appear, our destiny:

Theoretic truths... live as long as they are discussed, and they are made exclusively for discussion. But destiny—what from a vital point of view one has to be or has not to be—is not discussed, it is either accepted or rejected. If we accept it, we are genuine; if not, we are the negation, the falsification of ourselves. Destiny does not consist in what we feel we should like to do; rather it is recognised in its clear features in the consciousness that we must do what we do not feel like doing.

To put it another way, Ortega, being intelligent, articulate and thoughtful, may have had no wish to appear a prig and a buffoon, but, recognizing a higher necessity, accepted it as his duty.

Before I return this revolting waste of intellectual effort to the sewers of oblivion, let me ask if there be any just cause for its preservation.

Well, he can be amusing—as when he writes that “to think is... to exaggerate. If you prefer not to exaggerate, you must remain silent; or, rather, you must paralyse your intellect and find some way of becoming an idiot.”

Happily, Ortega found his way to being an idiot without paralysing his intellect, so he remains of interest to connoisseurs of old clowns. The study of history inevitably involves the study of clowns, cranks, hysterics, lunatics, obsessives and maniacs of every stripe, for history is a linear but densely cross-referenced catalogue of errors, blunders and confusions, both accidental and willful:

Th[e] disproportion between the complex subtlety of the problems and the minds that should study them... constitutes the basic tragedy of our civilisation. By reason of the very fertility and certainty of its formative principles, its production increases in quantity and in subtlety, so as to exceed the receptive powers of normal man... All previous civilisations have died through the insufficiency of their underlying principles. That of Europe is beginning to succumb for the opposite reason. In Greece and Rome it was not man that failed, but principles. The Roman Empire came to an end for lack of technique...

But to-day it is man who is the failure, because he is unable to keep pace with the progress of his own civilisation. It is painful to hear relatively cultured people speak concerning the most elementary problems of the day. They seem like rough farmhands trying with thick, clumsy fingers to pick up a needle lying on a table. Political and social subjects, for example, are handled with the same rude instruments of thought which served two hundred years since to tackle situations in effect two hundred times less complex.

So “it is man who is the failure,” whereas in the past it was the techniques of civilization that were inadequate to the challenges they faced.

But allow me to pose a question: wherein does the adequacy of a civilization lie which lacks the technique of educating its citizens? Ortega’s excuse is that “it has been found impossible to educate them,” but is this not to say that the techniques of education are presently lacking?

Our civilization grows ever more complex, and we are all part of it. It is a complex process which, at best, might be managed, but can’t be controlled—because it can’t, in its entirety, be anticipated. It is fantasy to imagine a superior type of man who, by virtue of his understanding, can both uphold and control it, if only the indocile mass will suffer to be told what to do:

The function of commanding and obeying is the decisive one in every society. As long as there is any doubt as to who commands and who obeys, all the rest will be imperfect and ineffective.

This is a fantasy the mass movements of Ortega’s time were willing to promote; but the indocility of the mass is one of the facts Ortega’s superior man, if he is to live in this age, must confront, and engage with. The mass is made up of individuals—even if not fully individualized. If they are too settled in their assortment of ready-made opinions, where did these ready-mades arise? The solution is not to make the mass more amenable to being led, but less: by preparing them to accept and exercise their responsibilities as individuals; by making them less content to adopt the ready-made opinions of others. If the mass has been hungry for these ready-mades, it is because certainty has its satisfactions, and they’ve been encouraged to adopt them.

Ortega says as much when he writes that

man, whether he like it or no, is a being forced by his nature to seek some higher authority. If he succeeds in finding it of himself, he is a superior man; if not, he is a mass-man and must receive it from his superiors.

He is this, or he is that. Much of the confusion of Ortega’s analysis comes from these hard distinctions. He talks of individuals (“In the presence of one individual we can decide whether he is ‘mass’ or not”) and of types (“from birth deficient in the faculty of giving attention to what is outside themselves”) and he is talking to us about them—except I rather doubt he’s talking to me. From where I stand, his analysis would make more sense if it addressed conditions and tendencies to which we are all subject. But maybe I’m just nettled because I’ve spent too long trying, with my thick, clumsy fingers, to pick up needles.

Of course, just because I can pass for a peasant in polite company doesn’t mean the peasants’ll take me in, so let me be obstinate in Ortega’s path and declare, as a point of principle, that I’d rather not be told what to do. And if this be my principle, it’ll do little good to accept, as my guide, the ready-made opinions of others, even if I’ve not given the matters they raise five minutes’ thought.

How, then, shall I form my opinions? By resistance to theirs, which is to say, by a critical unwillingness to accept glib nonsense as wisdom. Get used to resistance, Ortega, or go back to your para-feudal, pseudo-Liberal dung-heap. I am shocked by your radical ingratitude to the rough masses who feed you and clothe you, supporting you on their backs and prepared to indulge your leisure because, God help us, it is the price we pay for having men of ideas in our midst.

And yet, at this late date, I find myself wondering: does he maybe have a point? Because surely, as I look around, what I see are people who—let me not insist on their deficiency, their destiny or their duty—refuse every opportunity to think for themselves: some preferring instead to be stamped out as their fellows are stamped out, so that everywhere they look they might have the pleasing good fortune to see only themselves, magnified and reduplicated; others basing their right to an opinion on nonsensical absolutes invented by cranks and hucksters as a means of banishing honest doubt.

And do I fear them, as Ortega feared them?—because, resenting even the possibility that others may think in ways they have not been told to think, it is their ambition to abolish not only freedom of thought, but to stifle the need to think, and exterminate the thinkers?